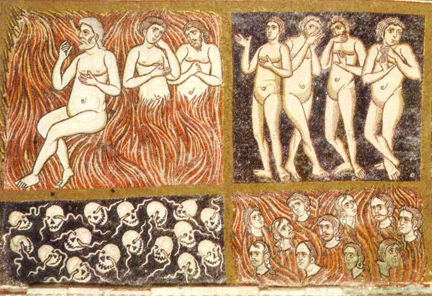

Unknown Artist. Sinners in Hell. Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta. Torcello (Italy). 12th century)

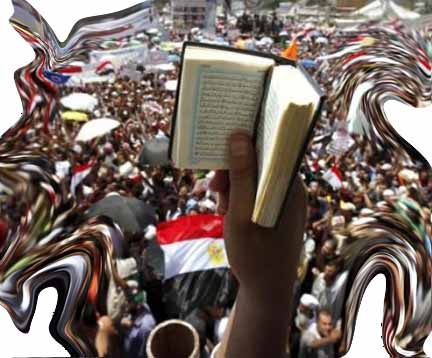

Yesterday I had the privilege of hearing a lecture by the anthropologist Talal Asad, who discussed the impact of the Arab Spring revolution in Egypt based on conversations he has held with Egyptians there and with a keen sense of historical insight. In the case of Egypt it is not just that it was sucked into strong-man rule for three decades under Mubarak, but that an entire generation has known nothing but cronyism and a firmly entrenched military elite still holds the reins, despite the street scenes on CNN. No one knows what exactly will happen next, least of all the media pundits who exude an expertise mentality that often borders on the ludicrous. One of the points that particularly struck me as poignant is the role of fear as a key aspect of all power politics. Mubarak, like Ali Abdullah Salih in Yemen and Ben Ali in Tunisia and even the Asad clan in Syria, have justified their self-serving iron grip as a quasi-secular bulwark against the specter of radical Muslims. They pretend to be the right kind of Muslims preventing the wrong kind of Muslims from taking over and returning the region to the 7th century. And Western nations, along with a number of Arab citizens, let fear dictate policy and overrule common sense.

Fear is on all sides, of course. Those who have dared to defy the power of the state have had good reason to fear, as the bloody security apparatus let loose in Syria amply demonstrates. Any trumped-up kind of “other” is an easy target for fear, especially when religious or ethnic identity is ascribed. In fact, as Talal noted, Mubarak went to great lengths to foster tension between Copts and Muslims in Egypt, creating fault lines for conflict where mutual cooperation had often been the norm. Religious sects do it to each other, dragging out the infidel charge and the heresy alibi whenever convenient. This is not at all unique to the Middle East or those who call themselves Muslims. When Rick Santorum states that President Obama does not base his policies on the Bible and Franklin Graham questions the president’s faith, religious passion is harnessed for political gain.

But what do we really mean by “fear”? Continue reading A World to Fear or of Fear?