by Jon W. Anderson

Amid the blizzard of punditry and spin-doctoring – especially spin-doctoring from perpetrators and advocates of prescriptions for Afghanistan who turned from the Bush administration’s original goal of smashing al-Qaida and denying it sanctuaries in Afghanistan from which the 9/11 attacks were hatched to destroying Iraq and “nation-building” in Afghanistan – it is worth pausing to take account of how the startling swift advance of the Taliban there from a border post to a provincial capital then to all other provincial capitals in less than a week and Kabul on the weekend looks from Afghan and perhaps even Taliban perspectives. So far, those have been limited to interviews with media-savvy Afghan modernists, on the one hand, and a Taliban press conference on the other. Or, all the news that fits the script(s).

What is new among facts closer to the ground is the much derided and in recent months ignored Doha “process,” if we might borrow that term. Doha is the proximal point of departure for everything that has happened in Afghanistan since the former Trump administration negotiated, signed, and exchanged copies of an agreement with the Taliban last year. From the outside, to external observers, this all looked very diplomatic, including accepting the Taliban as a de facto international player. Very diverting, and pundits were diverted into deconstructing it as variously hasty, overdue, giving up on Afghanistan, or a typical Trump deal, all show but bankrupt at its core. But that wasn’t the Doha Process from Afghan perspectives.

By setting a date for withdrawal of US troops on the ground in Afghanistan in return for Taliban agreeing not to molest that withdrawal, that Trump agreement with Taliban negotiator-representatives reset the game in two ways. First, it concluded armed hostilities in a classic Afghan form of conflict-management where one side concludes it cannot win, stops fighting, and effectively changes sides (while on the surface hiding that) by withdrawing from the field, with the other side accepting that instead of destroying its foe. Second, it provided a sort of non-aggression pact, or informal, more private than public, assurance that the withdrawing party would not be molested in return for effectively laying down arms. This underlying structure of the Doha Agreement from an Afghan perspective, on which foreign observers focused as leaving the Afghan government to make its own agreement, has a denser significance in customary Afghan approaches to conflict management. In those terms, the high-level Doha agreement provided a model subsequently applied “down the line,” as it were at all the points of actual armed conflict in myriad local discussions, agreements, and private assurances by Taliban that they would not molest or revenge themselves on soldiers who laid down (and especially surrendered) their arms nor civilians who didn’t oppose them. They may or may not have had a strategy to preserve and take over existing apparatus of government, as well as discarded military equipment much paraded before the cameras. But this much is basic: they managed a negotiated cessation of fighting and freedom of movement for themselves.

I don’t have direct evidence of myriad local negotiations and private assurances of this sort; but the alternative favored by external pundits – that thousands of soldiers and police, all of them, spontaneously and simultaneously deserted a government too corrupt, distant, and indifferent to their own welfare – is inherently implausible. It is implausible, first, that all would do this at the same time, as if Afghans were of one mind like a flock of pigeons and, second, that the occasional holdouts might not have been taken by Taliban as betrayal of the deal justifying their return to fighting. By all accounts so far, there was little of that and a lot of quietly stopping and simply stepping out of their way.

The structural condition for this outcome was set by the final US strategy of driving Taliban into the mountains and hinterlands while securing urban centers where most of the population lived. To old hands, this might resemble an old Vietnam strategy and defiance of the Maoist alternative, though it probably follows a more contemporary counter-insurgency doctrine of pushing insurgents to the margins so the centers can develop and develop constituencies for development. Again, I do not know if this was the rationale, but the effect of pushing Taliban out of sight was to push them out of mind and so to fail to register localizations of the Doha Deal for what they were, a deal and not just threats to kill any who opposed them.

Second, subsequent Afghan behavior supports the hypothesis of quiet assurances not just in Doha and not just in myriad local settings but all up and down the spectrum from local to national forces and government. The sudden night-time flight of President Ghani, a day after a final – recorded – broadcast in which he proposed to plan a meeting to mediate a national council to negotiate differences, followed the next day by not-so-former grandees who still represented important constituencies, some armed, stepping forward to announce that they stood ready to organize and host such a meeting with the Taliban, suggests the fix was in, notwithstanding his professions of sudden decision and sudden departures. Former President Hamid Karzai, current co-President Abdallah Abdallah, and surviving Mujahadin leader Gulgbeddin Hikmatyar interposed themselves with not-so-subtle reminders of other constituencies in Afghanistan, including armed ones, that Taliban would have to take into account.

While Taliban do not have such a reputation from their previous takeover and time in power, their performative defiance of the rest of the world in that period has so far (not this week but since the Doha Agreement) taken a back seat or at least been supplemented by professions of wanting international recognition following performances of such at Doha and in – of all things – a press conference in Kabul two days after Taliban fighters entered the capital. Whether a Conference of the Big Birds will occur, and whether it might include the volunteer grandees, the gesture and the roles claimed by persons making it are wholly Afghan. Call it speculation in settlement, jockeying for position, attempts to take the game ahead now that the game behind is up. This is the normal next phase in customary Afghan conflict-management: it is not de-escalation, not compromise or cutting the difference, but realignment that recognizes and accepts interests and a politics of alliance-making that begins with collusion. Even former President Ghani’s statements from his new not-yet-exile in the UAE are such a bid to, in journalist terms, “relevance.” In this regard, it may have been wiser than the pundits realized for US President Biden to blame the Afghan army for its debacle, since that cast him, an outsider, and not them as the betrayed party.

Where does this leave journalists and other observer-interpreters? For the most part, they have been outside the local versions of the Doha Process in Afghanistan; within Afghanistan they have been close to modernist constituencies that hitched their stars after the first Taliban period to the two domains that Taliban then forbade, especially to women – namely, education and media broadly interpreted to extend from fashion to broadcasting, publicity, and centering on expressive professions. These are most accessible to foreign observers, first, because they want to be – those are their reference groups – and second because foreign observers already have categories for them that provide a kind of pre-understanding that is at best thin when it comes to Taliban but also when it comes to the other demographic most threatened by them in the past, the Shia Hazara.

The coming test not just for the New Taliban but for the old grandees is who will take an interest in those Afghans in whom foreigners take an interest. This is not just the media world of commentators and interpreters focused by modernists, and particularly by urban women who have grasped the opportunities in education and media to measure the distance they have come from the last time Taliban were in power; it also must include the Shia Hazara whose marja (religious leader/exemplars) in neighboring Iran have deep networks among co-religionists in Afghanistan. This time, Iran is not a bystander and, for those who worry about such things, has two decades of experience recruiting and deploying third-party volunteers/mercenaries in its own regional adventures. Whether or not it could mobilize them, at the least, Iran would take an interest in direct threats to the welfare of Shia in Afghanistan. Arguably, the stability of Afghanistan going forward will depend on such negotiations and alliances formed that Taliban neglected (or rejected) last time but whose public spokesmen now profess to want to engage.

My only prediction is that the process will drive outsiders crazy, and lacking local points of reference will test abilities to tell their own. Among those local perspectives…

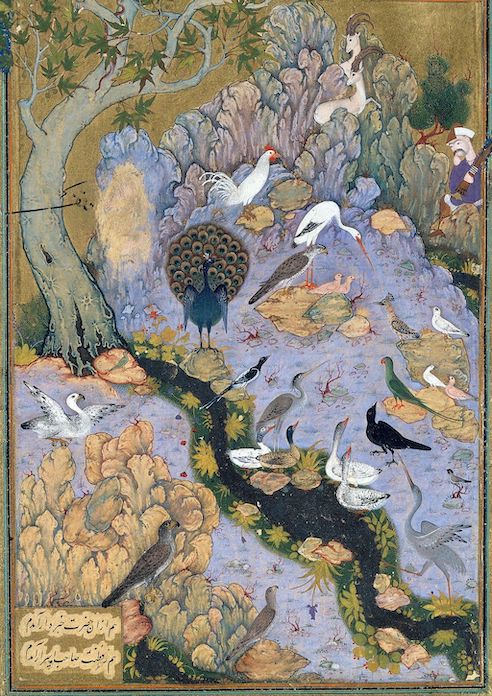

In The Conference of the Birds, the Persian Sufi poet Farid al-Din Attar of Nishapur (1142-1220) described a meeting of all the birds to decide who would be their sovereign. Each bird represented some human fault, and after some discussion the wisest urged that they seek out the Simorg. To do that, they had to pass through seven valleys, one where they abandon dogmas, one where they abandon reason for love, one where they abandon worldly knowledge, another where they abandon desires and lusts. In the Valley of Unity they realize that everything is connected, in the Valley of Wonderment that they have never understood anything, and in the final valley of Poverty that the ego is nothingness. The birds experience agonies and pain. Many die of fright even at the prospect of the journey, but some do set out, and a final 30 reach the abode of the Simorg (=30 birds in Farsi), which they realize is like the reality of a mirror in which one sees oneself reflected.

Jon W. Anderson is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at the Catholic University of America. He conducted ethnographic research in Afghanistan in the 1970s.