There is an excellent analysis in Time Magazine of how President Biden’s trip to the Middle East could help with resolving the protracted war on Yemen. You can read it here.

Category Archives: Huthis

The Crisis in Yemen

Geocolonialism and the War in Yemen

In April Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called the situation in Yemen the world’s worst humanitarian crisis. After more than three years of a lopsided war between a Western-supported Saudi/Emirati coalition and a rebel group in control of the capital Sanaa and most of the estimated 28 million Yemenis, the crisis is only getting worse.

Now coalition forces are attempting to wrest control of the vital port of Hodeidah from the Huthi forces, thinking that such a loss would force the Huthis to accept their terms for a total submission. Since this port supplies most of the food and aid entering Yemen, loss of the port would likely trigger a siege to literally starve the Huthi areas into submission. The Huthis know this and are not likely to give up the port without a bloodbath. Meanwhile several hundred thousand residents fear for their lives and many have already fled to areas with no resources whatsoever. The UN fears a renewed outbreak of cholera, which has already affected more than one million Yemenis. Negotiations continue by the UN Special Envoy Martin Griffiths to stop the impending violence.

But in the midst of all this turmoil, one recent pundit argues that the eastern province of Marib, firmly in control of the Saudi/Emirati alliance, shows how one province succeeds in the midst of Yemen’s war. Not only is this sparsely populated and oil-rich area considered a success, it is said to be “thriving.” A football stadium with German turf and according to FIFA standards is being constructed and there is a new university for 5,000 students. The biblical land of the Queen of Sheba and famous Marib dam mentioned in the Quran (which was bombed at one point by the Saudis) is said to be “regaining a slice of its historical importance.”

So what is the lesson for Yemen’s future from this miracle in the desert? For journalist Adam Baron “Marib’s experience holds wider lessons for Yemen’s future: embracing decentralisation, empowering local actors, and focusing on ground-up stabilisation are all strands of the story that international and local players interested in bringing peace and stability to Yemen should note.” The main local actor here is a tribal sheikh named Sultan Arada, drawing on support of the conservative Islah movement. With outside money pouring in, he has morphed into the sultan of a fiefdom. The current “stability” is grounded not on local concerns but from the top-down flow of money from the neighboring international players, Saudis and Emiratis.

Yemen’s future is not in Marib, nor in building state-of-the-art FIFA stadiums in a country with a ravaged infrastructure, ongoing water crisis and sectarian violence fueled by the grueling three years of war. Marib is currently a colony of the Saudis, just as the Emiratis would like to take control of the island of Socotra and the port of Aden. The two wealthiest states of the now moribund GCC are carving out their zones of influence on the backs of people in the poorest country in the Arabian Peninsula. Without the billions of dollars worth of weapons and strategic intelligence from the West, this war dividend could never have been realized.

Welcome to the latest, post-Cold War twist in the land once thought to be Holy. It is no longer direct Western intervention but a shared geocolonialism, in which the proxy war between Saudi Arabia and Iran is applauded and abetted by Western leaders. Muhammad bin Salman’s recent trip to the U.S. sold his snake-oil reform in exchange for buying more weapons and all that he assumes oil-drenched money can buy. Meanwhile the Saudi abysmal track record on human rights and the war crimes of the Saudi-led coalition in Yemen are ignored. If Marib is the model for Yemen’s future, then the only democracy, for its flaws, in the Arabian Peninsula will be geocolonized into yet another make-believe kingdom or emirate.

Cholera, Cluster Bombs and Summer Vacation

This post can be read at MENA Tidningen.

Reforming Saudi Arabia?

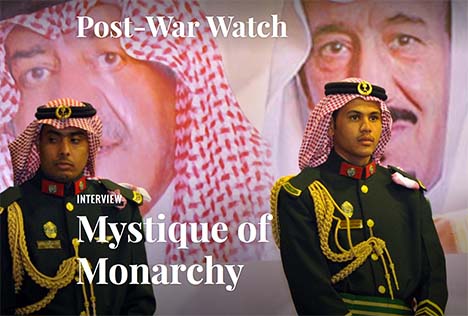

Mystique of Monarchy

Post-War Watch – April 19, 2016

https://postwarwatch.com/2016/04/19/mystique-of-monarchy/

MADAWI AL-RASHEED — Limited social and political reforms in Saudi Arabia only prolong the life of authoritarianism.

Although Saudi Arabia’s government relies on the religious establishment for its legitimacy, there are multiple groups and factions that fall under the Islamist category. How does the monarchy understand the relationship between Saudi’s religious establishment and political governance?

The dynamic at the heart of this question is better understood as one between religion and politics within the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The relationship between these two spheres has evolved through the twentieth century. There is not one way of describing the interaction between religious and political entities, simply because it is subject to the political will of the regime — and the government’s evolving connection to official Islam and Islamists’ discourses and practices. Ultimately, this relationship has gone through three distinct phases since the consolidation of the modern state

The first phase (1960s-1990s) can be described as one of cooperation and instrumentalization. Since the establishment of the modern Saudi kingdom in 1932, the al-Saud political leadership tried to cooperate with the religious establishment in their country. The royal family institutionalized their discourse by creating specific religious bodies and honoring key figures for their support of the regime. Saudi Arabia’s government claimed legitimacy as the leadership that applies Islamic law and protects the Holy Cities — as well as directs outreach to Muslim communities around the globe. The regime’s efforts to incentivize religious bodies to support the monarchy derived potency from the fact that Saudi’s religious groups operated according to a populist ethos: religious figures can reach people in mosques, schools, universities, as well as exercise control over the judiciary.

The second phase began in the early-1990s, following the 1990-1991 Iraqi invasion of Kuwait. During this period the Saudi regime alternately repressed and accommodated opinions from the multiple voices within the religious establishment and the splinter groups around it. Saddam Hussein’s military operations posed a serious threat to Saudi Arabia’s security and economy. The royal family understood that it needed to bring foreign, non-Muslim soldiers onto Saudi soil to defend the Kingdom — an action that angered conservative religious elements. Immediately after the Iraqi invasion, the Saudi regime began repressing Islamist voices that dissented against cooperation with United States and other foreign militaries.

The Voice of which America?

Commentary on MENA Tidningen.

Photoshopping the Yemen War

A new post on MENA Tidningen…

Blame the Huthis…

Click here for my post on Tigningen about yet another bombing in Aden.