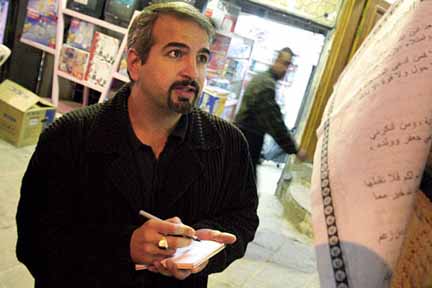

The late Anthony Shadid

[The recent passing of New York Times reporter Anthony Shadid leaves a large gap in their coverage of the ongoing crises in the Middle East. Here is his last article on the political climate in Tunisia.]

Islamists’ Ideas on Democracy and Faith Face Test in Tunisia

By ANTHONY SHADID, The New York Times, February 17, 2012

This article was reported and written before Mr. Shadid’s death in Syria .

TUNIS — The epiphany of Said Ferjani came after his poor childhood in a pious town in Tunisia, after a religious renaissance a generation ago awakened his intellect, after he plotted a coup and a torturer broke his back, and after he fled to Britain to join other Islamists seeking asylum on a passport he had borrowed from a friend.

Twenty-two years later, when Mr. Ferjani returned home, he understood the task at hand: building a democracy, led by Islamists, that would be a model for the Arab world.

“This is our test,†he said.

If the revolts that swept the Middle East a year ago were the coming of age of youths determined to imagine another future for the Arab world, the aftermath that has brought elections in Egypt and Tunisia and the prospect of decisive Islamist influence in Morocco, Libya and, perhaps, Syria is the moment of another, older generation.

No one knows how one of the most critical chapters in the history of the modern Arab world will end, as the region pivots from a movement against dictatorship toward a movement for something that is proving far more ambiguous. But the generation embodied by Mr. Ferjani, shaped by jail, exile and repression and bound by faith and alliances years in the making, will have the greatest say in determining what emerges.

Their ascent to the forefront of Arab politics charts the lingering intellectual and organizational prowess of the Muslim Brotherhood, a revivalist movement founded by an Egyptian schoolteacher in a Suez Canal town in 1928. But intellectual currents that once radiated from Egypt now just as often flow in the other direction, as scholars and activists in Morocco and Tunisia, perched on the Arab world’s periphery and often influenced by the West, export ideas that seek a synthesis of what the most radical Islamists, along with their many critics here and in the West, still deem irreconcilable: faith and democracy.

More often than not, they are asking societies for trust that, given the experiences of Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution or the Islamist-led coup in Sudan in 1989, authoritarian leaders and secular forces are reluctant to offer.

Mr. Ferjani, a 57-year-old self-taught intellectual as exuberant as he is pious, acknowledges the doubts. In one of several interviews, he declared that history — a word he uses often — would judge his generation not on its ability to take power but rather on what it did with power, which has come after four decades of activism.

“I can tell you one thing, we now have a golden opportunity,†he said, smiling. “And in this golden opportunity, I’m not interested in control. I’m interested in delivering the best charismatic system, a charismatic, democratic system. This is my dream.â€

A Chance Encounter

Nothing in Mr. Ferjani’s childhood really set him on the path to realize this ambition. Born in Kairouan, a town reputed by some Muslims to be Islam’s fourth holiest city, he was not especially pious as a child. His father, a shopkeeper, never managed to provide enough for his family. He remembered going three days without food once, and wearing cheap sandals to school. “Poverty, we tasted it,†he recalled.

By his own account, he was unruly and rambunctious until he turned 16. That year, Rachid al-Ghannouchi, an Arab nationalist turned Islamist who had studied in Egypt and Syria before returning to Tunisia, took a job teaching Arabic in Kairouan. Mr. Ghannouchi would stay only a year before setting out to eventually form the Islamic Tendency Movement, then the Ennahda Party, but he left a legacy with his students.

“He was always talking about the world and politics,†Mr. Ferjani said. “Why as Muslims are we backwards? What makes us backwards? Is it our destiny to be so?â€

The questions posed by Mr. Ghannouchi have shaped successive generations of Islamists, a term that never captures their diversity. The theme was examined in the work of Hassan al-Banna, the founder of the Muslim Brotherhood, whose notion of missionary work proved so successful over 50 years. It was there, too, in the works of Sayyid Qutb, an Egyptian thinker whose writings resonated long after he was hanged in 1966, helping give rise to a militant Islamism that bloodied the Middle East. Later, “The Hidden Duty,†a text that laid the groundwork for the assassination of Anwar Sadat in 1981, tried to resolve the issue. So did Mr. Ghannouchi, who endorsed pluralism and democracy, even as revolution raged in Iran.

In Kairouan’s colonial-era Negra Mosque, Mr. Ferjani and a hundred other youths gathered to study them all. “Read, read, read, read,†he recalled. “Even when I walked, I read.â€

Mr. Ferjani eventually made his way to Tunis, the capital, where he joined his old Arabic teacher’s group. “Politics was there from the beginning,†he said in the interview.

Tunisia was ruled at the time by Habib Bourguiba, who was so secular that he once made it a point to drink orange juice on television during Ramadan, the Muslim month of fasting. Mr. Bourguiba, in power since 1957, cracked down on Mr. Ghannouchi’s followers, and with the prospect of many of them being executed, Mr. Ferjani said he helped in plotting a coup d’état. He met many of the organizers at a video store he ran in a low-slung building of white stucco and blue shutters, across the street from Parliament.

Seventeen hours before they were to carry it out, Zine el-Abidine Ben Ali, Mr. Bourguiba’s interior minister, led his own coup. Ten days later, on Nov. 17, 1987, Mr. Ferjani was arrested. He spent 18 months in jail, where his interrogators strapped him to a bar in what he called “the roasted chicken†position and fractured his vertebra with an iron rod. Unable to walk, the pain searing, he would be carried by prisoners on their backs whenever he had to move.

“They were extreme experts in how to make the torture felt in every part of the body,†Mr. Ferjani recalled. “I would stay awake until 5 a.m. in the morning. I’d pray till dawn, then I’d sleep, and I’d only fall asleep because there was nothing left in me.â€

Five months after his release, still in a wheelchair, he trained himself to walk 50 yards so that security would not notice him at the airport. He shaved his beard and borrowed a friend’s passport. Then he caught a flight to London and sought asylum.

Crucible of Exile

Islamists of Mr. Ferjani’s generation wear prison time like a badge of honor. But exile, especially for the Tunisians, was often no less formative.

The London where Mr. Ferjani traveled became a hub of sorts for Islamist politics in the 1990s. Mr. Ghannouchi soon arrived there, joining Mr. Ferjani. Salafis from Saudi Arabia mixed with their frequent adversaries, Shiites from Bahrain, finding more common ground in London than at home.

Ahmed Yousef, a scholar and Hamas leader in the Gaza Strip, recalled a similar environment in the United States, where he made lifelong contacts at conferences in Washington. Among the connections: Saadeddine Othmani, a Moroccan scholar and politician; Ali Sadreddine Bayanouni, a Syrian Brotherhood leader; Abdul Latif Arabiyat, an Islamist leader from Jordan; and Abdelilah Benkirane, a Moroccan who is now the prime minister.

The environment became less permissive after the 1993 bombing of the World Trade Center in New York, Mr. Yousef said, but until then, “it was like paradise.â€

“In exile, people feel they need each other,†said Azzam Tamimi, a Palestinian scholar and activist in London, who has written a biography of Mr. Ghannouchi. “Back home, the national environment imposes itself on you. Priorities become different.â€

Mr. Ferjani compared his years in London to the intellectual awakening he underwent in Kairouan in the 1970s. Settling with his wife and five children in the neighborhood of Ealing, he remained in Islamist circles, soon embroiled in the debates over Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden, but broadening his horizons into civil society. He took classes on the history of Europe, democracy, the environment and social change.

He said he understood what Mr. Tamimi called the “common roots and common ground†of Islamist activists, many of whom never expected to return home.

“We know each other,†he said. “But knowing is one thing, doing things together in every sense — as many may think — is another. In politics, it’s not that we all agree.â€

Embracing Democracy

Through Mr. Ferjani’s years in exile, the dominant image of political Islam was the bloody record of Egypt’s insurgency in the 1990s, the Algerian civil war and the ascent of Bin Laden, whose Manichaean view of the world mirrored the most vitriolic statements of the Bush administration.

But no less dramatic was the shift under way within various currents inspired by the Muslim Brotherhood. Mr. Ghannouchi, his own thoughts evolving in exile, became an early proponent of a more inclusive and tolerant Islamism, arguing a generation ago that notions of elections and majority rule were universal and did not contradict Islam. Early on, he supported affirmative action to increase women’s participation in Parliament, a break with the unrelenting notion of missionary work that so long defined the Brotherhood.

“Frankly, the guy who brought democracy into the Islamic movement is Ghannouchi,†Mr. Ferjani said. As Mr. Ghannouchi himself put it in an interview late last year, at a conference in Istanbul attended by Islamist activists from Tunisia to the Palestinian territories, “Rulers benefit from violence more than their opponents do.â€

In debates that played out across the Arab world, though often ignored by the West, the questions of reconciling democracy and Islam raged from the 1990s on. In the middle of that decade, a young Egyptian Islamist named Aboul-Ela Maadi broke from the Brotherhood and formed the Center Party, declaring its support for elections and the alternation of power and, as important, dissent and coalitions with non-Islamic parties.

Sheik Yusuf al-Qaradawi, an enormously influential Egyptian cleric based in Doha, Qatar, often sided with the progressives. (In 2005, he turned heads by declaring on Al Jazeera satellite television that “freedom comes before Islamic law.â€) Though the Brotherhood still resents Mr. Maadi for his defection, it has largely adopted his ideas, which had seemed so novel in 1996.

Those debates reverberated across the region. Mr. Yousef, the Palestinian, remembered the impact of reading Mr. Ghannouchi’s monthly magazine, Al Maarifa, as a student in Egypt. In Libya, Ali Sallabi, who once debated politics with jihadists in the prisons of Col. Muammar el-Qaddafi, cited Mr. Ghannouchi and Sheik Qaradawi as inspirations.

Critics view the shifts as tactical, even rhetorical. But the very essence of the debates has marked a fulcrum in the intellectual currents of today’s political Islam.

“Al-sama’ wa’l-ta’a,†went the old Brotherhood ideal, which translates as “hearing and obeying.â€

“That’s over,†said Tariq Ramadan, a prominent Islamic scholar based in London and a grandson of Mr. Banna, the Brotherhood founder. “The new generation is saying if it’s going to be this, then we’re leaving. You have a new understanding and a new energy.â€

He noted that in contrast to Mr. Ferjani’s earlier years, when Egypt was the source of new Islamist thought, the influences are now more pronounced of exiles in Europe, scholars in North Africa like Mr. Ghannouchi and Ahmed Raysouni, and Islamist parties like Ennahda in Tunisia and Mr. Benkirane’s Justice and Development Party in Morocco.

“It’s not coming just from the Middle East anymore,†Mr. Ramadan said. “It’s coming from North African countries and from the West. There are new visions and there are new ways of understanding. Now they are bringing these thoughts back to the Middle East.â€

From his perch in London, Mr. Ferjani incorporated talk of Westminster when formulating his idea of a charismatic state, whether led by Islamists or others. After vehemently rejecting the left, he now embraces Karl Marx’s critique of capitalism.

Exile, he said, “changed me a lot, profoundly.â€

Applying Theories

On a brisk winter day, Mr. Ferjani sat in Ennahda’s offices in Tunisia, a five-story building whose plastic sign inscribed with its name lent a sense of the unfinished.

Nearly a year had passed since he had returned to Tunis, draped in the red national flag and walking effortlessly through the airport. He carried a passport that was his. His beard had gone gray, save for a mustache that served as a reminder of his youth in Kairouan. About 200 people met him at the terminal.

“No place for traitors in Tunisia, only for those who defend her!†he sang, joining the crowd as it recited the national anthem. “We live and die loyal to Tunisia.â€

On this day, his mood was more somber. In protests, secular activists were denouncing the caliphate that they believed was sure to rise from the victory of Ennahda in elections in October. Newspapers opposed to the party were full of stories of abuses by puritanical Islamists and Ennahda’s supposed tolerance of extreme practices. In well-to-do cafes, some Tunisians viewed Ennahda’s success in existential terms, talking of an inevitable intolerance sanctioned by religion that would extinguish Tunisia’s cosmopolitanism. The cultural debates seemed to overshadow what everyone agreed was more pressing: an ailing economy.

“Frankly, we’re on top of things,†Mr. Ferjani said.

But in a less guarded moment, he asked, “Can you really solve problems of 50 years in less than one month with a government that is less than one month old?â€

In an interview, Mr. Ferjani had once quipped, “You know, power corrupts.†As he sat at the party headquarters on this day, he wrestled with those questions of power. Next to him were stacks of the party’s newspaper, The Dawn. One column railed against “counterrevolutionary mediaâ€; another darkly hinted at conspiracies. The front page declared, “Parliament is against sit-ins and for listening to the demands of the people.â€

“We don’t fear freedom of expression, but we cannot allow disorder,†he said. “People have to be responsible. They have to know there is law and order.â€

He suggested that protesters should obtain permission from the police. He worried that the news media was too reckless. He hinted that the forces of the ancien régime were still plotting. In the cramped room, his exuberance had turned stern, and his words were hesitant.

“Everybody has to be careful not to be dragged into a dictatorial instinct, no matter what happens,†he said. “We can’t lose the soul of our revolution.â€

This, he said, was the test.

David D. Kirkpatrick contributed reporting from Cairo.