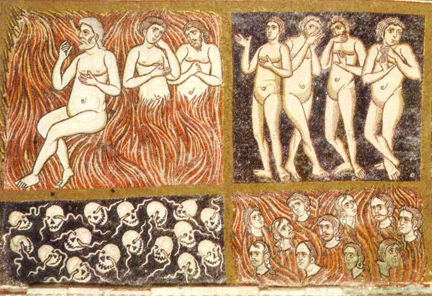

Unknown Artist. Sinners in Hell. Cattedrale di Santa Maria Assunta. Torcello (Italy). 12th century)

Yesterday I had the privilege of hearing a lecture by the anthropologist Talal Asad, who discussed the impact of the Arab Spring revolution in Egypt based on conversations he has held with Egyptians there and with a keen sense of historical insight. In the case of Egypt it is not just that it was sucked into strong-man rule for three decades under Mubarak, but that an entire generation has known nothing but cronyism and a firmly entrenched military elite still holds the reins, despite the street scenes on CNN. No one knows what exactly will happen next, least of all the media pundits who exude an expertise mentality that often borders on the ludicrous. One of the points that particularly struck me as poignant is the role of fear as a key aspect of all power politics. Mubarak, like Ali Abdullah Salih in Yemen and Ben Ali in Tunisia and even the Asad clan in Syria, have justified their self-serving iron grip as a quasi-secular bulwark against the specter of radical Muslims. They pretend to be the right kind of Muslims preventing the wrong kind of Muslims from taking over and returning the region to the 7th century. And Western nations, along with a number of Arab citizens, let fear dictate policy and overrule common sense.

Fear is on all sides, of course. Those who have dared to defy the power of the state have had good reason to fear, as the bloody security apparatus let loose in Syria amply demonstrates. Any trumped-up kind of “other” is an easy target for fear, especially when religious or ethnic identity is ascribed. In fact, as Talal noted, Mubarak went to great lengths to foster tension between Copts and Muslims in Egypt, creating fault lines for conflict where mutual cooperation had often been the norm. Religious sects do it to each other, dragging out the infidel charge and the heresy alibi whenever convenient. This is not at all unique to the Middle East or those who call themselves Muslims. When Rick Santorum states that President Obama does not base his policies on the Bible and Franklin Graham questions the president’s faith, religious passion is harnessed for political gain.

But what do we really mean by “fear”? On the one hand there are those who think there is such danger in the world that we should always be afraid, very afraid. Bill Young notes that the Rashaayda Bedouin of the Sudan divide their immediate world into their camp, the symbol of safety, and the wilderness where the jinn and enemies roam. Such a scenario is played out over and over again in the ethnographic record across cultures. This is not so much a fear of the unknown as it is a fear of that which may not be controlled. Yet the idea that there is a world out there to fear readily blends into a mindset that fear is a way of living in the world. If there are things to fear out there, at least one can try to avoid those things or find ways to navigate safely through them. But if the world is made up out of fear itself, a solipsist original sin dogma that offers no hope for redemption in this life, then we are trapped by the very notion of fear. Hell is already here and not confined to any imagined hereafter.

Fear is not all bad. But being forced to live in fear may be as bad as assuming that fear is the only way to live. Certain fears can be conquered and the exhilaration of overcoming what one feared is evident in the wake of the Arab Spring. But old fears can not be twittered away or crushed by protest slogans; they tend to get recycled or rebranded and ultimately focus on new targets. This is not a cynical call to accept pessimism as a Solomonic truth. As Talal noted at the end of his talk yesterday, despite the looming problems there is cause for optimism that somehow Egyptians, as I believe also for the others breathing in the air of hope for a better life, will muddle through. Egypt will not see a perfect democracy. This is not because it is Egypt but because the very idea of a perfect democracy is a myth held together these days by a neoliberal sprinkling of secular pragmatism.

In the end I am drawn back to the inspiring line of FDR that the only thing we have to fear is fear itself. It may not be the only thing, but it is often the most important thing to remind ourselves that the world we should really fear is the world created by fear.

Daniel Martin Varisco