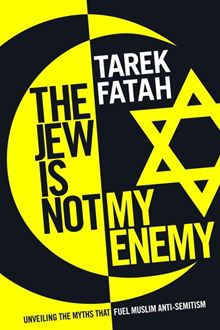

The following is a review of The Jew Is Not My Enemy: Unveiling the Myths that Fuel Anti-Semitism by Tarek Fatah, published by McClelland & Stewart

ISBN: 978-0-7710-4783-1 (0-7710-4783-5). The review is written by Ivan Davidson Kalmar and published in the Literary Review of Canada, March, 2011.

As Tarek Fatah, the author of this provocative book, puts it, “By all rational standard, Muslims and Jews should have been, and could be, partners. Their faiths are very similar (…). There were even times when Muslims and Jews prayed together around the tone covered today by the Dome of the Rock [in Jerusalem].†Certainly in the imagination of western Christians at least, Muslims and Jews were for centuries regarded as two of a kind.

From the medieaval theologians through to Hegel, Islam was considered to be a revival of Judaism (which Christians thought should have died with Christ). Though the attitude to both Jews and Muslims has generally been hostile, it was not always so. For example, Jews and Muslims were both admired by nineteenth century romantics as possessors of an eastern spirituality that inspired and could continue to inspire the Occident.

When Jews and Arabs were both classed as members of the same “Semitic†race, “Semite†was at first often meant as a compliment. It was partly in reaction to romantic accounts of the Semites that the term “anti-Semitism†was invented by a new breed of Jew-haters. And it was, in turn, largely a reaction to modern anti-Semitism that the old idea of “returning†the Jews to the Orient took hold in the form of modern Zionism. Zionism led to a long and still ongoing, bloody conflict between Jews and Muslims over the holy land of Israel/Palestine.

The notion of Jewish-Muslim kinship took a blow with every Muslim (or Christian) Arab removed from his or her home, until the founding of the State of Israel in 1948 caused Muslims and Jews to be thought of as eternal enemies, not only by the Christian West, but by themselves as well.

In order to know the unkind views that many Jews hold about Islam and most Muslims today, you don’t have to be Jewish, you just need to talk to ordinary Jews. Long gone are the days when the Jews of New York or Vienna proudly erected “Moorish style†synagogues that recalled their Semitic kinship to their Arab cousins. Tarek Fatah, however, looks not at Jewish Islamophobia, but at the corresponding prejudice in his own community: Muslim anti-Semitism. The topic is not new. The classic is Bernard Lewis’ Semites and Anti-Semites, from which Fatah quotes here and there.

But Fatah is among the very few Muslims to have broached the subject. This, in an obvious sense, gives him credence with non-Muslim readers. It is also more likely to give offence to Muslim ones. Indeed, those familiar with Fatah’s career as a Canadian Muslim critical of Islamic radicalism know of the considerable hostility towards him, not only by Muslim fundamentalists but even by fellow Muslims with moderate views who object to his bold pronouncements on Muslim causes and on Islam. Undeterred, in The Jew is Not My Enemy, Fatah asks whether anti-Jewish prejudice is not anchored in the very depths of his own religious tradition.

To answer that question, he probes various areas of the Muslim sacred tradition, in chapters with titles like “O Allah, Completely Destroy and Shatter the Jews;†“The Jews of Banu Qurayza;†and “Muhammad comes to the City of Jews.†The first-mentioned chapter quotes a recent sermon on Egyptian television to describe contemporary Islamist Jew-hatred, but the focus is on how such prejudice relates to the murders perpetrated by Pakistani terrorists at a Jewish center in Mumbai at the time of the November 26, 2008 attacks in that city.

The other two chapters named above relate the spirit of such contemporary hatred to old Islamic traditions about the Jewish tribe of Banu Qurayza in Medina. These traditions revolve around a story with which few in the West are familiar. The Banu Qurayza were Jewish residents of Medina, the city to which Muhammad fled from Mecca. These Jews are said to have betrayed the prophet to his enemies, although they did not take part in combat. It is said that Muhammad’s forces, victorious in the so-called Battle of the Trench, then massacred the Jewish men in cold blood. The mass murder is held out by many Islamists as both evidence of Jewish treachery and as a prescription for how to deal with it.

Such uncompromising attitudes are reinforced, says Fatah, by regular features of the mosque liturgy such as the formula that ends many Friday evening sermons, “Oh Allah, defeat the kuffar.†Kuffar can be translated as “infidel†or “unbeliever,†but Fatah interprets it, and says that imams often interpret it, as “Jews and other non-Muslims.†Though many Muslims would object to such an interpretation, I am sure that Fatah is right that that is just what many others have in mind. It is an example of traditional, or fairly traditional, Muslim material that can be co-opted in the service of jihadist extremism.

Most of such extremism, as informed people know, does not go back to medieval Islam so much as to its relatively recent reinterpretation by Muslims, partly in reaction to western-induced modernity. For all of its use of Islamic sources, current Islamist anti-Judaism derives principally from exposure to western-style anti-Semitism, which has nothing to do with Islam.

The immediate culprits are nineteenth and twentieth-century theorists such as the Egyptian radical Islamist writer Sayyid Qutb, well exposed to western thought, whose writings Fatah discusses in some detail. In this context, Fatah gives the correct evaluation to Arab collaboration with the Nazis during World War II. It was far outweighed by indifference and by cooperation with the British, but to the extent that it did exist it was motivated by opposition to Jewish activities in Palestine. Today, classic western anti-Semitism of theProtocols of the Elders of Zion variety, as well as Holocaust denial, find more takers in the Muslim worlds than in their original European homelands. Muslim anti-Semitism is very real and is increased by the conflict between Israel and the Palestinians, for which, Fatah suggests, Israel is to blame in part. Even so, anti-Semitism is not traditionally Muslim at all.

At least, it is not very traditionally Muslim. Fatah does find anti-Jewish prejudice not only in modern western-inspired texts but also in the classic Muslim sources: I have already indicated his coverage of the Banu Qurayza incident and the anti-kuffar prayer. So does he accept that Islam as such is anti-Semitic? Not quite. Fatah delves a long way into the tradition to denounce Islamic anti-Semitism, but not all the way.

In the chapter called “Is the Quran Anti-Semitic?†and elsewhere, he exonerates that Holy Book of anti-Jewish prejudice. Instead, he attributes anti-Semitism to post-quranic Muslim literature, such as the Hadithand the Sira, compilations that purport to record quotes, events and biographical details relating to Muhammad, but which Fatah says are largely false. Thus he notes that the massacre of the Banu Qurayza by Muhammad’s forces is not mentioned in the Quran, but only in the Sira.

He agrees with Prof. Salam Elmenyawi, a controversial Muslim academic, that “the Quran preaches respect for Judaism,†and then quotes Elmenyawi to the effect that “In Hadith literature … which Muslims have made part and parcel of Islamic teaching, you cannot respect the Jew, the Jew is God’s enemy until the end of time.†In short, he contrasts the divinely given Quran with the humanly constructed Hadith and Sira, and accepts the former as unprejudiced while blaming the latter for its anti-Semitism.

Now it is true that even the most conservative Muslim scholars admit that the Hadith and the Sira are less trustworthy than the Quran, though some of the Hadith are considered more reliable than others. Yet Fatah’s move is unconvincing. It is remarkable how closely the Elmenyawi/Fatah argument mirrors earlier maneuvers to save the reputation of Judaism in gentile eyes. Nineteenth and early twentieth century Reform Jews eliminated, or radically altered, everything from kosher food laws to a belief in afterlife, if it seemed to contradict respectable modern, liberal positions held in the secularizing West. They argued that the undesirable injunctions came not from the Hebrew Bible but from its interpretation and development in the humanly constructed Talmud (which the Hadith recall in so many ways). They then rejected the Talmud, purportedly to better reflect the spirit of the original Bible.

There are at least two things wrong with that kind of reasoning. First, it gives rise to suspicions of hypocrisy. It is hard to believe that its enlightened proponents really believe that even the Hebrew Bible or the Quran are word-for-word the gift of God. Second, they appear to agree with the very fundamentalists they criticize, when they accept the false premise that there is such a thing as the one correct, unchanging reading of the Quran or the Bible. In fact, religion is always a growing tradition of practice and wisdom and never, in spite of both the fundamentalists and the Fatah-style reformers, something that has a meaning fixed in an original ancestral time. But then, I suspect that Fatah knows this. He may just be recognizing that to maintain a common identity among generations of a religious community, any reinterpretation of a holy text must, paradoxically, insist that it is in fact the original interpretation.

For the notion that the Quran preaches respect for Judaism is, in spite of what Fatah suggests, at least at the explicit level, clearly a reinterpretation. The Quran is a complex document. Some of it seems friendly to the Jews, and a lot of it seems quite the opposite. Unlike Fatah, I am not laboring under the imperative to demonstrate faith in an infallible holy book, so here’s a thought: why not admit that all religion is flawed and in need of continuous improvement? In this it is no different from other morally uplifting things like love or democracy. Even nature and, contrary to his reputation perhaps even God, have their faults. This conclusion forces itself upon anyone who is prepared to study without prejudice the holy texts of any of the Abrahamic faiths.

The Hebrew Bible teaches, among other questionable acts, genocide against interfering tribes such as the sons of Amalek. The New Testament denies heaven to those who won’t accept Jesus, and promises to cast the unbelievers into a lake of fire after affecting them with “foul and loathsome†sores.

The Quran, too, promises a very hot place for unbelievers. Pagan idolaters will be “the fuel of hell; they shall groan with anguish and be bereft of hearing.†When it comes to Jews and Christians, though, the Quran is much more forgiving. Fatah is correct that the Banu Qurayza story is not found in the Quran. Similarly, stories of the violence visited by Muhammad’s men on two other Jewish tribes, the Banu Nadir and the Banu Qaynuga, are also spelled out only in the post-quranic literature (although their authors and readers assume that the Quran alludes to them implicitly). Fatah refers, even, to passages from the sura “The Repast†in the Quran, which may be interpreted to maintain the continuing validity of God’s promises to the Jews, including their possession of the Holy Land / Israel. At the start of the book, he quotes a less ambiguous passage from “The Heifer:†“… those who are Jews, and the Christians, and the Sabians, / Whoever believes in God and the Last Day, / And does good, they have their reward with their Lord.â€

But Fatah is a hafiz, [I am not] a Muslim who has memorized all of the Quran. Surely he knows the rest of “The Heifer.†It makes it clear that the “good†Jews who will be rewarded are only “a few†(verse 88). As for the rest, “… they rejected God’s revelations, and killed the prophets unjustly†(verse 61). They continue to display this tendency towards unbelief “now that a messenger from God [Muhammad] has come to them, … even though he proves and confirms their own scripture†(verse 101). Verse 41 explicitly conjoins the Jews to “believe in what I [i.e. God through Muhammad] reveal.â€

The sura “The Amramites,†however, states that “Some of them do believe but most of them are wicked.†Fatah ignores most of these passages, though he does include another passage from “The Amramites:†“Degraded they shall live wheresoever they shall be / Unless they make an alliance with God and alliance with men.†In the context, it is quite clear that the “alliances†offered here require submission, if not conversion, to Islam. And that, for any self-respecting Jew, is far less than “respect for Judaism.â€

None of this is to deny that Fatah has produced a highly informative, lucid book that should be read by anyone interested in the relationship between Muslims and Jews and, indeed Muslims and Christians. It will be particularly enjoyed by those who admire chutzpah, the spark that comes from combining intelligence with personal courage.

Fatah’s courage includes facing the inevitable charges that in criticizing anti-Semitism in his own community he is damaging Muslim honor. But Fatah is a gentleman, and he does the honorable thing to focus on prejudice in his own community, rather than on the Jewish side. I hope that Jewish, or Christian or Hindu or atheist, readers are similarly honorable, and will not turn Fatah’s book into an indictment of Islam. Nor should they use it to ask the useless and irrelevant question as to which is more vicious, Muslim anti-Semitism or Jewish Islamophobia. The proper response to this thoughtful, even if mildly flawed, book is to have the courage to expose and reject anti-Muslim falsehoods, within our own traditions. And within our own selves.

Ivan Davidson Kalmar teaches in the Department of Anthropology, University of Toronto. His recent writing and lecturing has been on the joint construction of Jew and Muslim in western Christian cultural history. His latest book, Imagined Islam and the Notion of Sublime Power, will be published by Routledge in 2011.