In September 2005 I started the blog Tabsir (“Insight”) with several other colleagues to provide information on the Middle East as a supplement to the news and to note items of interest. The blog has been in hibernation since late 2018 as I simply had no time to keep it going. I am reviving the blog for posting items time to time and hope to involve several other academic colleagues as well.

Palestine in 2019

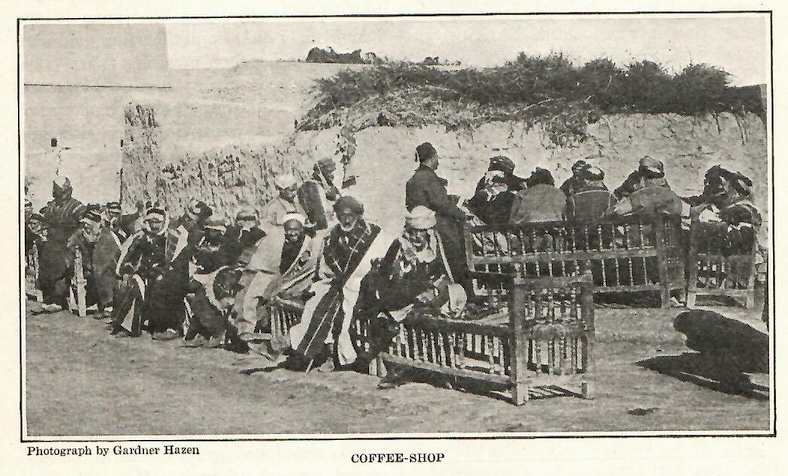

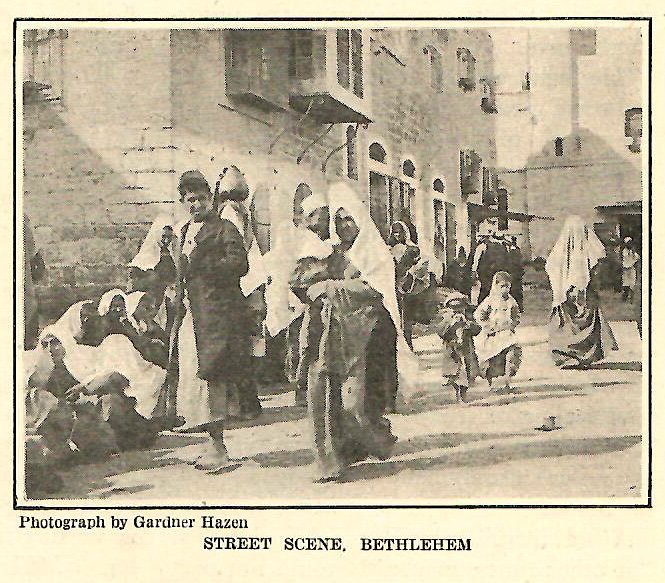

Over the years many popular magazines have published articles by visitors to Palestine. In a 1919 issue of the periodical The Century there was an article by Joseph Koven, an American Jewish author who visited Palestine. His article is very Orientalist, describing the local Arabs as dressed in rags and primitive. I cannot recommend reading the actual article, but there are several photographs and I attach two of those here.

Queers for Palestine

Since Israel’s invasion of Gaza on October 27th, launched in response to an attack on Israel by Hamas on October 7th, there have been thousands of demonstrations held worldwide. Some of these demonstrations have included LGBTQ+ groups, voicing their support for a free Palestine, calling for a ceasefire and an end to the occupation. Pundits and laymen alike have reacted to this, often portraying queer solidarity with Palestine as a contradiction, calling it “bizarre” or jokingly comparing it to “chickens for KFC.”

These reactions prompted a group of more than 300 Swedish LGBTQ people to write a response, published in the Swedish newspaper Sydsvenskan, explaining that their support for Palestine may only appear bizarre to those who view human rights as conditional. The article is published in Swedish, but what follows here is a summary in English.

The group highlights the strategic rhetorical manoeuvre of equating support for Palestine with support for Hamas, similarly to how critique of Israel is equated with antisemitism. In fact, many LGBTQ groups have criticised Hamas and brought attention to the marginalisation of LGBTQ people in Gaza. Meanwhile, those pundits who ridicule Queers for Palestine have rarely showed any interest in LGBTQ rights in the past, and only do so now in order to defend Israel against its critics rather than to defend queer Palestinians.

Furthermore, the argument that queer Palestinians can find refuge in Israel is at best a half-truth. Israel has long banned any Palestinian – regardless of sexuality or gender identity – from working or settling permanently in Israel. Only in 2022 they decided to permit LGBTQ Palestinians from the West Bank temporary work permits. These, however, are short term and need to be renewed every other month, with the intention that Palestinian LGBTQ migrants eventually move to a third country. Israel does not recognise Palestinians’ right to asylum, although a court order in January 2024 ruled that LGBTQ Palestinians may request asylum. This decision is something that the current Interior Minister wants to see reversed.

The article also responds to the claim that Israel supports LGBTQ rights. This is part of what is called “pink washing,” meaning that Israels actions are justified with reference to their LGBTQ politics. This claim does not account for how the Israeli Defence Force (IDF) has been blackmailing queer Palestinians, forcing them to act as informants under threat of being “outed” (that the person’s sexuality or identity is revealed to others without their consent). In other words, Israel has been using LGBTQ people as pawns, constituting a direct threat against their lives but also contributing to a distrust against the queer community in Palestine, worsening their situation.

Notably, same-sex relations were decriminalised on the West Bank some 37 years before Israel (1951 compared to 1988), and it was due to Israeli occupation and application of Israeli law that same-sex relations were criminalised again on the West Bank. Of course, today it is easier to live openly as a gay person in Tel Aviv than it is in Gaza or the West Bank, but it is not on equal grounds. There are also several Palestinian organisations working to improve LGBTQ rights in Palestine whose works are impeded and made immensely more difficult by Israels continued and intensified occupation.

Lastly, the article affirms that queer support for Palestinians’ right to live in peace and free from occupation is not conditional on Palestinians’ views on LGBTQ rights. It is irrelevant whether or not those suffering under Israel’s invasion and blockade of Gaza and occupation of the West Bank believe homosexuality is immoral and should be banned. Neither Israel nor any outsider may dictate which party should rule in Palestine. However, the war, blockade and occupation constitutes the biggest obstacle to the liberation of LGBTQ Palestinians. The signatories of the article say that no liberation can be achieved under war and occupation.

The full text, in Swedish, can be read here.

The full list of signatories can be read here.

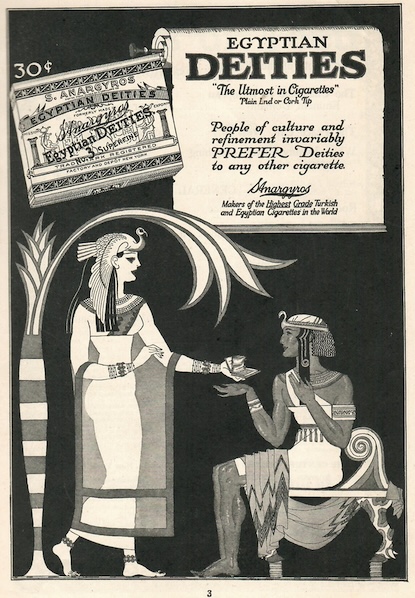

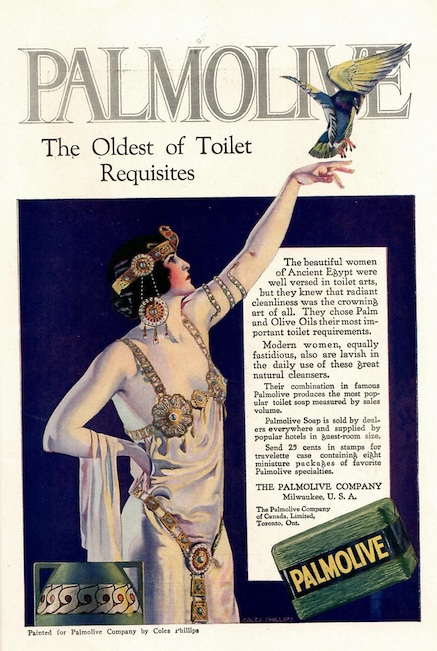

Lighting Up Egyptian Style

Egypt has long been a land of wonder for advertising. In the March 1919 periodical ‘The Century’ the very first ad is for a brand of cigarettes so divine they could be offered to Egyptian deities. Of course this tobacco is for “People of culture and refinement” in an age before lung cancer was thought about. However, there was the saving grace of Palmolive soap, “The Oldest of Toilet Requisites.” Clearly, “that radiant cleanliness was the crowning art of all.” So whether you want to light up or wash up, you can do it like the ancient Egyptians. At least you could in 1919.

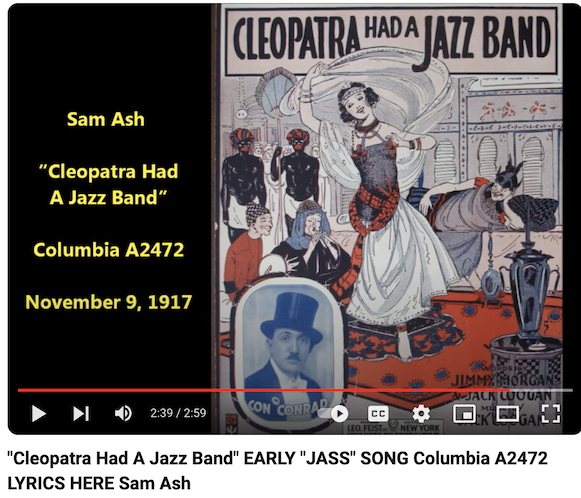

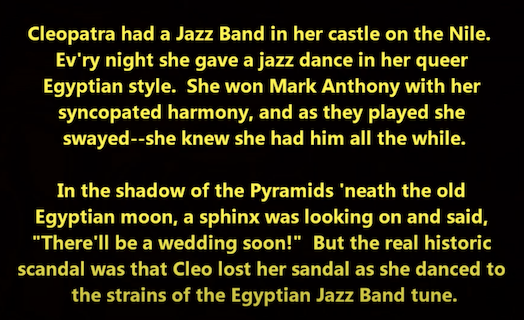

Cleopatra had a Jazz Band

There are quite a few songs from the early 20th century Vaudeville Days that feature the Middle East. Did you know that Cleopatra had a jazz band? Feel free to sing along. Here is the Youtube video.

Bunk is not Bunn: A Silly Claim about the Origin of Coffee

In a non-academic website called Atlas Obscura, there is an article with the entertaining title: “Before Drinking Coffee, People Washed Their Hands With It.” The article was written by Nawal Nasrallah, an Iraqi scholar who has published excellent work on classical Arabic recipe books. However, this particular article is anything but sound scholarship. Her main argument is that a “mysterious ingredient” very similar to coffee was known five centuries before the documented appearance of coffee, known in Arabic as “bunn“, as a drink. “However, instead of bunn, it was called bunk, and rather than drinking this ingredient, it was mostly used for cleaning and freshening the hands,” she argues.

Her argument is flawed from the start. She is aware that the 9th century Ibn Masawayh defined bunk as an aromatic coming to Iraq from Yemen. He clearly identifies it as coming from the trunk wood of a plant called Umm Ghaylan. However, Nasrallah says Ibn Masawayh was confused, without indicating why. The link to the wood of Umm Ghaylan is also made by al-B’iruni, who adds that it is a Persian term, and by other scholars. Umm Ghaylan is a well-known name for a species of acacia grown on the Arabian Peninsula. Nasrallah was unaware that the renowned botanical scholar Abu Hanifa al-Dinawari, a contemporary of Ibn Masawayh, described Umm Ghaylan as a synonym for talh, the well known term for several acacia species, including the major gum arabic variety. Al-Dinawari also noted the terms for the parts of the tree, specifically defining bunk as the bark (laha) of the acacia tree. This term for bark is still in use in Saudi Arabia. So unless these early scholars were making it up, which I doubt, the meaning of bunk is clearly established. The claim that a 16th century traveler named Leonhard Rauwolf said that the coffee beans he saw being roasted (he never saw the tree) were the same as the term bunk used centuries earlier is hardly reliable proof, especially since Rauwolf assumed that the term bunn for coffee was no different than the earlier term bunk. It was not unusual for writers at this time to make such claims without any real evidence.

Nasrallah writes that early medical scholars like al-Razi and Ibn Sina describe the qualities of bunk “to check the unpleasant odors of sweat and the smell of the quick-lime used in baths to remove hair,” but no mention is made of it as a drink. It is a serious stretch of logic to suggest, as the author does, that when Ibn Sina said that “consuming bunk had mind-altering properties, ‘which could affect the intellect,’” this was proof that this was the first time anyone had pointed out the impact of caffeine. It is not unusual for herbals to comment on the impact of certain substances on the mind, so such a general statement does not imply caffeine from coffee.

In addition to ignoring the clear identification of the plant, which is not mysterious at all, Nasrallah can cite no evidence from Yemen for such an identification. If the coffee plant was indeed coming from Yemen in the 9th century, why is there no reference in any Yemeni text to it? The geographical text of the 9th century al-Hamdani mentions numerous plants, but not any known term for coffee, nor the term bunk. Nor do the agricultural and medicinal treatises of the Rasulid era (13th-15th centuries) refer to coffee. The known documented sources suggest that coffee came from Ethiopia as a drink useful for Sufis; this was probably sometime in the latter half of the 15th century. By 1500 it had spread widely from Yemen and even prompted a legal meeting in 1511 to determine if it was licit for Muslims, as discussed in an article by the historian Jon Mandaville.

The speculation continues with the following claim: “As for coffee as a hand-cleaning product, it seems that the spread of good-quality colored and perfumed soaps eclipsed its popularity. As bunk itself faded away, so did the knowledge of what it was used for.” To suggest that by the 16th century no one used traditional plant products for aromatics or for hand washing is ridiculous, as such practices have continued into the last century. To assume that perfumed soaps were widely available among a population that was still mainly rural and poor is silly. To think that the drinking of coffee took off after several centuries of hand-washing is wishful thinking. There is no evidence at all that the term bunk, which is not related to the coffee term bunn, ever referred to anything other than a product of the acacia tree. To argue otherwise is pure bunk.

Lament for Yemen

Yemen,

your body lies crushed

beneath the rubble that was the home

where you were born

your blood floods the land

where sorghum supplied every need

your breath is a raging wind,

a gasp in the swirling dust

but despite all odds you cling to life,

you sing, you dance, you will not be denied.

Sanaa,

your towering buildings bow down

in prayer for the dead

the saila swells with your tears

Bab al-Yemen closes its eyes

blinded in dark nights more dense

than locusts devouring all they see

but as the bombs flash

hope shines through the alabaster

carved by your grandfathers’ hardened hands.

Yemen,

your past is like no other

your present is not of your doing

no matter how many bombs fall

how many families mourn

how long the world ignores you.

The smile of one of your children

will outlast all the vain kings in their palaces.

Your future will not be denied.

Daniel Martin Varisco, February, 2022

[Words can no longer describe the suffering inflicted on the people of Yemen; the damage is beyond comprehension, where only poetry can dare to speak.I wrote this poem more than a year ago, but it is as relevant today as it will be for some time to come. But I stress the last line for an amazingly resilient people.]

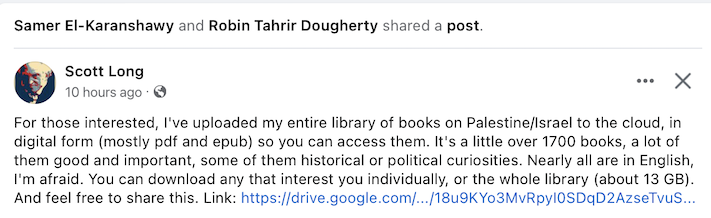

1700 Books on Palestine

To access these books, click here.

The Ignorance of the Jahiliyya

This is an excellent Youtube talk by Ahmad al-Jallad on the evidence from the rock inscriptions and graffiti from the Arabian Peninsula. Also check out his excellent book on religion and ritual in the Safaitic graffiti.