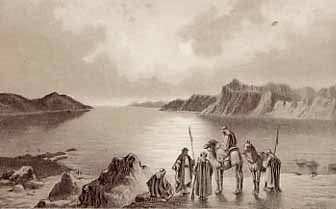

The Dead Sea from Thomson’s “The Land and the Bookâ€, opp. p. 614

Almost 150 years ago one of the most popular travel accounts of the Holy Land was penned by an American missionary named William M. Thomson. Born in Ohio, my own home state, the 28-year old Thomson and his young bride arrived in Lebanon in 1834 as Protestant missionaries. This was a mere 15 or so years after the first American missionaries had made the Holy Land a mission field. At once an entertaining travel account and Sunday School commentary on the places and people of the Bible, this may have been one the most widely read books ever written by a Protestant missionary.

Reading Thomson is like reading one of the early English novels. The language is less familiar, although still thoroughly Yankee and the devotional tone has long since disappeared for a readership buying out The Da Vinci Code as soon as it hit the bookstores. The biblical exegesis, literalist yet frankly pragmatic at times, is intertwined with astute and at times humorous accounts of the people Thomson met along the way. But the style is not at all dry or discouragingly didactic. From the start Thomson engages in a dialogue with the reader, making the text (which stretches over 700 pages in the 1901 version) a rhetorical trip in itself.

Among the wonders described by Thomson is the Dead Sea, which as a devout literalist he interpreted through the biblical tale of the brimstone destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah. Yet, he is quite interested in the geologic and chemical character, as he notes:

Of course, the old and rather taking theory, that the Jordan, before the destruction of Sodom, ran through Wady ‘Arabah to the Gulf of ‘Akabah, must be abandoned. This would demand geologic changes, reaching from the Lake of Tiberias to the Red Sea, too stupendous to have occurred within the period of man’s residence upon the earth. Still, this grand chasm, valley, or ‘crevasse’, running, as it does, between the two Lebanons, through the whole length of the Jordan, and along the ‘Arabah to the Elantic Gulf, and even down that gulf itself into the Red Sea, is among the most remarkable phenomena of our globe; and it is not certain to my mind that there was at one time a water communication throughout this long and unbroken depression.

How do you account for the nauseous and malignant character of the water of the Dead Sea?

This is owing to the extraordinary amount of mineral salts held in solution. The analysis of chemists, however, show very different results. Some give only seventy parts of eater to the hundred, while others give eighty, or even more. I account for these differences by supposing that the specimens analyzed are taken at different seasons of the year, and at different distances from the Jordan. Water brought from near the mouth of that river might be comparatively fresh, and that taken in winter from ‘any part’ would be less salt and bitter than what was brought away in autumn.

One analysis shows, chloride of sodium, 8; potassium, 1; calcium, 3. The very last I have seen gives calcium, 2 4/5; chloride of magnesium, 10 1/2; of potassium, 1 1/3; of sodium, 6 1/2. The specific gravity may average about 1200, that of distilled water being 1000. This, however, will vary according to the time and the place from whence the specimens are taken.

[Excerpt from William M. Thomson, The Land and the Book; or, Biblical Illustrations Drawn from the Manners and Customs, the Scenes and Scenery of the Holy Land. London: T. Nelson and Sons, 1901, pp. 623-624, Original, 1859]

For the previous post in this series, click here.