Archeological sites in Bani Hushaish suffer from vandalism

by Mansur Ali al-Muntasir, Yemen Observer, February 3, 2009

The Bani Hushaish district in the Sana’a governorate is 30 km east of the capital, and contains several important archeological sites.

Yemen has a great wealth of ancient archeological sites many of which date as far back as the pre-Islamic era and many more site which are still waiting to be discovered and documented. There is a fear though amongst the Yemen’s archeological establishment that without adequate protection and preservation much of Yemen’s historical record could be lost to natural and human damage. This article seeks to highlight the richness of Yemen’s archeological heritage and the need to preserve and document such heritage for future generations.

The most important of the discovered archeological sites is in Shibam al-Ghras, where several mummies were found. The district contains several other neglected sites, which have not yet been identified by archeological authorities. This is disturbing; as these sites have been damaged as a result of official negligence, and a lack of public awareness about their value and importance to Yemeni heritage.

The rocky graves discovered at Shibam al-Ghrasi have contributed significantly to the existing knowledge of the historical Yemeni practice of embalmment, especially after the discoveries made by an archeological team from Sana’a University in 1983. This important historical site is the best known in the area, but not the only one. The following report seeks to shed light on these other sites.

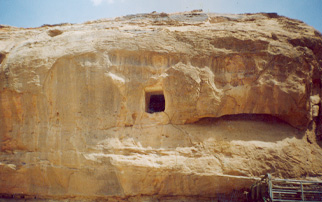

The area in which the mummies were discovered, Jabal Thi Marmar, in Shibam al-Ghrasi in Bani Hushaish, is situated 27 km north-east of Sana’a. This site also contains several ancient monuments, many from the pre-Islamic period, and others from the Islamic era. The most important discovery in this area was the rocky graves where the mummies were found, though there have also been several mosques and fortresses documented in this area.

Studies carried out by Sana’a University state that similar monuments have been found in Wadi Thahr, Shibam-Kokban, Thabhan, Bait ilman, Thafar, Mafkath, al-Hada, Mughrib Ans, Anis, al-mi’sal and in other areas.

In his book, Dr. Abdulhalim Noradin describes his work as, “an introduction to Yemeni archeological science.†Dr. Noradin says that the Sukhaim tribe used to consider Shibam an important center, which seemed to have a wide influence over Kholan. Al-Hamdani an expert in Yemeni archaeology says that the tribe included a group of Yemeni Gails (ancient Yemeni rulers), who managed to acquire great power. Some may have even been the contemporaries of the king of Saba Ail- Sharh- Yahsub, who may have lived during the second century BC.

In his book, Dr. Noradin said the discovered mummies, now housed in the Sana’a University Faculty of Arts Archeological section, were found in two graves dug into the mountain. The mummies were initially in bad shape because they had been exposed to improper handling. Several University professors took part in the excavation process, and found several of the mummies shrouded in seven layers of leather, lined with an inner layer of flax. The researchers discovered the mummies had been treated with chemicals which left traces, which may indicate that ancient Yemenis had an understanding of embalmment.

An analysis by an Egyptian team of experts has shown that the mummies are dated from 280 BC, making them over 2000 years old.

For more details, we went to the museum section at Sana’a University, where we met archeological specialist Ismail al-Mahagri.

He said: “the Shibam al-Ghrasi discovery added new knowledge about the process of embalmment in ancient Yemen, as well as the building of the graves of kings. This has provided new information about our heritage because it was widely thought that the Egyptians were the only people to have discovered the process of embalmment. However, the discovery of these graves at Shibam al-Ghrasi has placed Yemen in second place in the ancient eastern world regarding this practice.

He added that Yemeni embalmment has unique characteristics, which are different from those of the Egyptians. The dead are placed in a squatting positioning, with the knees supported by a wooden crutch. The abdominal cavity was stuffed with the Ra’a plant, which is well-known in Yemeni pastures. Al-Mahagri continued, “despite the historical importance of the mummies, they are not accorded their due significance.â€

He went on to say that the relevant authorities, such as the archeology authority, should not leave these mummies in the museum, where they are subjected to disintegration. He added that modern serums and materials should be provided to help preserve them, as they are an important part of Yemeni heritage.

Regarding other archeological sites which may not have been surveyed and registered by the authority, Khlid Mahdi Garallah, the archeology office manager at Bani Hushaish said there are several sites which have not yet been surveyed, including Lakmat al-Qradie in Harf. It is a monumental site dating back to the BC period. The ruins at the site indicate that there was a military barracks set up to guard the route to Thafar, Sana’a, Marib and Hadramout through the al-Sir valley. This was shown through the inscription of several names, and a portrayal of the Goddess Ashtar in the form of an Ibex on a red limestone rock.

The grave is located at the entrance of Wadi Karsana, which branches off from Wadi al-Sir. It is a fortress, which rises 100 meters above the wadi and contains many important monuments which need to be studied. He added that the site was mistreated thirty years ago, and the stones and sculptures were plundered by the neighboring residents. Currently, new buildings are being built at the bottom of the site by locals.

He added that there are stone graves at the site; similar to the one found at Shibam al-Ghrasi. The monuments seem to be a tribute to the al-Khimion rulers in Shibam al-Ghrasi. There are also the remains of an ancient dam, dating back to the Himiari period, and several important monumental sites in Lakmat al-Sharaf, and the Shoja’ al-Sharafa plateau. Here, there is a Musnad inscription which dates back to the sixth century BC, from the era of King Asa’d al-Tobai’ (Asa’d al-Kamil,), thought to be the last to repair the roads linking Wadi al-Sir with Bani Hushaish. This inscription was damaged by recent road construction.

There is also another important monument site at al-Hoqala, in the Hirab area. It lies in a high rocky area, in the form of a fortress; the site includes several buildings and wells.

Another important monument is the al-Alaq steps at the village of Rasih, which contains a number of Sabai and Himiari inscriptions in Mosnad writing. This is in addition to the marvelous sanctuary called the prophet Iob’s grave. It contains a number of rocky caves, old mosques, dams and other artifact, and dates back to the pre-Islamic era.

There are also several other sites distributed across the district in Sauan, al-Ronah and others which have not yet been surveyed or discovered. Even sites which have been discovered and studied by staff from Sana’a University at Shibam al-Ghrasi have not yet been surveyed as studies were confined to the mummies.

The district archeological office manager concluded by saying, “we hope that the district and archeological authorities will attend to the monuments, because they contain ancient artifacts and Islamic sites which need be studied, preserved and protected.†He called on authorities to provide the physical and technical requirements for the office to enable it to protect the country’s heritage.

During an interview with our correspondant the manager of the archeological office described the difficulties faced in preserving and documenting archeological finds.

Regarding the difficulties facing the district’s archeological office, Khalid Mahdi explained that the office lacks support, technical expertise and the tools used in the survey and discovery processes, such as D.B.C. devices. He demanded the general authority pay his team to undertake field and office works, adding that work at the office remains a voluntary activity.

The office also interviewed a number of inhabitants in the find areas to try to ascertain public awareness with regards to archeological preservation and awareness about the value of monuments in their district.

– Fifty-year old Ali Mohammed Atia, said these monuments are public property. The masterpieces and monuments found inside them become the possessions of those who find them, because they are our ancestors’ legacy. It is like fishing at sea. He added that the simple layman is more deserving to it than thieving officials. He justified his argument by saying they are common property, and as long as the state is not attending to them, the simple layman has a greater right to them because he is a member of the community. He added that as they are neglected property, it is lawful to take them.

Twenty-nine year old Nabil Ahmed Noman said “it is not easy for the simple layman to be aware of the archeological value of these monuments, saying he cannot differentiate them from similar jewelry. The average man cannot identify their historical value; all he thinks about is their material value. A man who places an old stone as a decoration at the front of his house is a good example of such mentality. Yet, if people become aware of their value, they will think only of the financial return, forgetting about their historical value. However he corrected himself by saying that a newspapers seller once put a historical monument on his papers to keep them from being dispersed by the wind, not knowing that the piece is more valuable than his papers. He concluded by saying that the relevant archeological authorities should facilitate opportunities to interested persons and researchers to allow them to increase their historical knowledge concerning these sites. He also added that relevant authorities should exert appropriate efforts to promote awareness regarding the value of history through different media outlets.

Finally, the historical monuments at Bani Hushaish remain neglected by officials, a matter which contributes to a lack of public awareness.