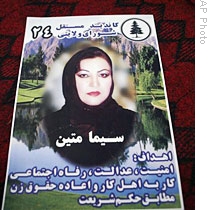

An election poster in Kapisa province for Sima Matin, a female candidate in a provincial council election, 28 Jul 2009

John Burns Answers Your Questions on Afghanistan

By John F. Burns, The New York Times, August 19, 2009

After more than 30 years as a Times foreign correspondent, I’ve grown used to looking out of the aircraft or jeep or train on arrival in unfamiliar and often inhibiting terrain, and wondering with a mixture of anticipation and anxiety how quickly, and capably, I’ll get my professional bearings — and justify the editors’ faith in assigning me. The boundary I’ll be crossing with this new venture for “At War,†our new and expanded blog on the conflicts of the post-9/11 era, is a different kind of challenge — but just as daunting, in its way, as those old forays into unknown lands.

In the first 48 hours after our Web editors invited readers to send in their questions, more than 220 of you responded, a degree of interest that is encouraging for what it suggests about the potential for us at the Times of this kind of interactive journalism. Just as much, the flow of questions, and the sophisticated commentaries woven into many of them, have been a reminder of how much many of our readers already know about the complex challenges America confronts abroad.

We’ve heard from Americans who’ve served in Afghanistan in the Peace Corps, as diplomats, and as military personnel, as well as from scholars and others with specialized expertise in the area — and, no less, from individuals with no personal ties to Afghanistan but a deeply impressive grasp of the issues involved. So for this new undertaking to work at its best, we should aim at developing this new enterprise into a conversation, one from which we can all benefit, not least myself.

Working with the editors, I’ve tried to find the common themes in the first wave of questions, with a view to responding to as many as possible over the next few days. The main topics of concern appear to be these: Why are our forces in Afghanistan, and can we ever leave, at least in any acceptable period of time?

Is democracy really possible there, or are we wasting our time? Is Afghanistan capable of evolving into a modern society, or will all efforts there founder on the deeply conservative forces entrenched there? Is President Hamid Karzai an ally we can depend on, or a man that the Bush Administration chose in haste to lead post-Taliban Afghanistan in December 2001, saddling the country and its Western allies with an ineffectual, corrupt and crony-ridden leadership? If we can’t depend on President Karzai, is there anybody else?

But ahead of all these issues, for now, is the question of the presidential and provincial council elections that take place tomorrow, which seem like the best place to start.

Q.

It’s kinda a sham election isn’t it? An incumbent, propped up by the “powers that beâ€â€¦challenged by dozens and dozens of mostly no-name challengers. …Why do we go thru the motions of pretending “elections†are taking place? Not just there, but in far too many places around the world…I realize the NYT can’t ignore them, but the vast majority of your readers already know the outcome of this cart before the horse sham exercise —– Ken in Phoenix

A.

You’re far from alone in doubting the value of the Afghan elections for the presidency and provincial councils that are taking place on Aug. 20, Ken. Among the dozens of questions we’ve had about them, the overwhelming majority are deeply skeptical, with many calling them a “sham†in the context of the violence in Afghanistan, and the lack of a social, economic and political culture that can engender western-style democracy. Dr. Richard H. Fish asked how it is possible to hold a fair election in the face of violence and intimidation from the Taliban; another reader, O Coelho, concluded that “the whole thing smacks of African-style ‘democracy, ’ holding elections ‘at gunpoint.’†James, another contributor, suggested that it’s “foolhardy†to try and bring democracy to “a very complicated, warlord-controlled, tribal-based, backward, agrarian and poor countryâ€. And so on.

My sense of it is that even if the elections are a long way from meeting the minimal standards that would be accepted in much of the developed world, and they undoubtedly are, they are far better than having no elections at all. You only have to ask what the reaction around the world would be if the United States and its coalition allies in Afghanistan declared that it was impossible to conduct elections, and adopted some other way of choosing the country’s leaders – let’s say by holding another loya jirga, or grand tribal council, of the kind that confirmed Hamid Karzai as interim president until he faced his first nationwide election in 2004. The cries of “puppet!†and “stitch-up!†would be deafening. Better, surely, to hold elections that are flawed, but that offer at least a rough-and-ready sense of the popular will, than to capitulate to the Taliban’s menaces and hold no elections at all.

More than 30 years ago, when I was the Times correspondent in South Africa, I learned a valuable lesson from Harry Oppenheimer, that country’s gold and diamond magnate, and a man who used some of his enormous wealth to fund the above-ground opposition to apartheid.

He said his effort to ameliorate the miseries imposed by South Africa’s apartheid racial laws was based on an ancient maxim he had learned from Charles de Gaulle, “Don’t let the best be the enemy of the good,†meaning that the pursuit of an unachievable ideal should not be allowed to frustrate the acceptance of an achievable but flawed “next-best†solution. Afghans, of course, would like the kind of elections Americans enjoy, but the ones they are being offered are surely a far, far better way of assigning power than any offered by the ruthless men of the Taliban.