The Mothers Of The Lashkar

by C.M. Naim, Outlook India, Dec 15, 2008

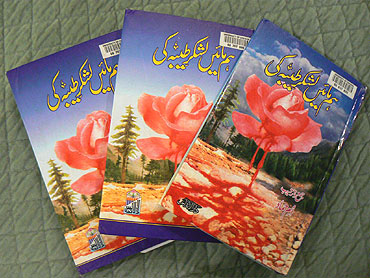

The book is titled Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e-Taiba Ki (‘We, the Mothers of Lashkar-e-Taiba’); its compiler styles herself Umm-e-Hammad; and it is published by Dar-al-Andulus, Lahore. Its three volumes have the same garish cover, showing a large pink rose, blood dripping from it, superimposed on a landscape of mountains and pine trees The first volume, running to 381 pages, originally came out in November 1998, and was reprinted in April 2001. The second and third volumes, with 377 and 262 pages, respectively, came out in October 2003. Each printing consisted of 1100 copies. Portions of the book—perhaps much of it—also appeared in the Lashkar’s journal, Mujalla Al-Da’wa.

Here is how the publisher, Muhammad Ramzan Asari, describes the book’s contents and purpose.

The book at hand, Ham Ma’en Lashkar-e Taiba Ki, is a distillation of the tireless labor and far-flung travels of our respected Apa (‘Elder Sister’), Umm-e-Hammad, who is in-charge of the Lashkar’s Women section, and also happens to be an Umm-e-Shahidain (‘Mother of Two martyrs’)…. [I could be misreading the text, for I found no reference to any of her sons except one, whom she described as a very much alive mujahid.] Her poems are on the lips of the mujahdin. Numerous young men read or heard her poems and, consequently, set out to perform jihad, many of them gaining Paradise…. Our workers should make this book a part of the readings for the ladies at homes to awaken the fervour for jihad in the breasts of our mothers and sisters. (I.13.)

In her preface, Umm-e Hammad describes her own conversion to the cause at some length.

Once I was among those who considered jihad the root of big trouble [fasad], and vociferously called it that. I hated the Markaz. I considered it to be the den of a gang that lured innocent boys away from their homes and schools only to throw them into the inferno of battle in Kashmir, making them a sacrifice to its own end of collecting Riyals and Dollars from foreign sources. Then I noticed that my husband, Asif Ali, whose organizational name is Abu Hammad, had grown closer to Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib. He had known the latter fairly well for many years, but now he would often remark at home: ‘I’m raising my children with prohibited money because I work in a bank.’ I immediately knew that something was not right. Realizing that the man had fallen into the clutches of the so-called ‘saviours’ of Kashmir, I quickly took some counter-steps to protect my family. I took every loan offered by the bank to make the man’s burden of debt heavier. In brief, there was Abu Hammad, suffering because he felt he was earning an illegitimate living, and there was I, ensuring my own comfortable future by adding to the load he carried. I would constantly tell him, ‘We eat of only what we actually earn. We work hard. We meet our duties.’ But, while Satan helped me find arguments and excuses, Allah, the Almighty, was determined to open the doors of His help and guidance to one of his guileless, well-intending servants. And so, one morning that simple man left home for the bank as usual, and handed in his resignation. On the way out of the bank, he paused at the threshold and vowed never to cross it again. He then went to the Markaz, and from there proceeded directly to Afghanistan, to the very first training centre of the Lashkar at Jaji.

It was as if some monstrous calamity had hit the family. There was no abuse that I didn’t throw at the Markaz and its director, and no crime I didn’t charge them with. Still dissatisfied, I consulted with the family, obtained the address from Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib, and showering curses on that ‘gang of frauds’ went to the Muzaffarabad office of the Markaz.

What I did there must have pleased Satan a great deal. May Allah forgive my sin.

But after I had seen how the mujahidin lived—their hard training, their fervour, their deep faith—I soon began to examine my own ugly past, when I had lived as if I were blind, deaf, and mute. A deeply humiliating sense of remorse came over me. I listened to the lectures given by the teachers at the Markaz, and realized that I had been totally ignorant of Jihad fi Sabil-allah (‘Jihad in God’s Path’), which endows any Muslim with all the dignity and power in the world. I asked myself: how is it that Muslims everywhere are victimized by infidels? Why are they brutalized and humiliated despite the prayers, fasts and pilgrimages they perform? I now turned to the Qur’an. I read Surah Anfal (chapter 8), Surah Tauba (chapter 9), and other verses on jihad; I listened to discourses on these verses; and I came face to face with that resplendent aspect of Islam which in our history recalls the mothers of Salahuddin Ayubi, Tariq bin Ziyad, Muhammad bin Qasism, and Mahmud of Ghazna. All praise to Allah, for His great kindness. That was the first miracle of that journey in jihad. Our hearts were transformed…. May the Almighty forgive us the nineteen years of disobedience—our eating the bread of usury from the bank….

In a second introductory note, Umm-e Hammad throws some light on the genesis of her book and of the Lashkar. The group, according to her, started its militant activities at Jaji, in Afghanistan, where it joined hands with the Salafi Afghans of Nuristan in their battle against the Soviet forces. (In the book itself, several ‘martyrs’ are described to have received military training and seen action in Afghanistan. In one account the future ‘martyr’ even describes how the Arab mujahidin made fun of the Pakistanis fighting beside them.) Subsequently, the Lashkar entered the Kashmir valley, with ‘less than 700 mujahidin ranged against 700,000 satanic forces.’

After a rhapsodic paean to the mujahidin’s alleged successes, Umm-e-Hammad continues:

Then the wielder of this broken pen noticed that the mothers and sisters, whose hopes and desires, dreams and wishes, provide the blood that colors the shattered bodies of the Lashkar mujahidin, live in purdah [and can’t be seen]. And so this humble woman, considering it a duty to unveil [their feelings], presented the idea to Hafiz Muhammad Sa’eed Sahib, the Amir of the Markaz, who strongly encouraged me. A few days later, Zakiur Rahman Lakhwi, the Amir of the Lashkar, and Abdur Rahman Al-Dakhil, the Amir of the Occupied Valley, set out to meet with the families of the martyrs who lived in Punjab. When my son Hammadur Rahman learned about it he decided to be my mahram—[legitimate male companion]—and obtained the permission from [Hafiz Sa’eed]. [On 16 December 1995] our group set out for its first meeting, with the mother of the Shahid Imran Majeed Butt of Faisalabad…. After collecting the blood-drenched words and the stars-like sentiments of the mothers and sisters of more than one hundred martyrs of the Lashkar, our caravan returned home on January 11 1996. (I.19.)

Subsequently, Umm-e-Hammad travelled to Karachi and parts of Sindh in a similar manner. Again, while the men talked with the male members of the families, she met with the women to take down their recollections of their ‘martyr’ sons or brothers. Chiefly the book is based on her notes, but on occasion she fills in gaps from the files of the Lashkar’s journal, Mujalla Al-Da’wa.

While the first volume of the book was clearly compiled by Umm-e Hammad, the two subsequent volumes, while carrying her name, seem to be the work of male party hacks.Particularly the third volume for it badly lacks all the little personal touches that Umm-e Hammad adds to the stories in the first volume; much of it simply brings together the overblown prose that first appeared in the Mujalla.

The first volume of the book describes 81 ‘martyrs’, the second 58, and the third 45. Taking into account a few repetitions and unlisted additions, the rough total of comes to 184. In this small sample—the Lashkar claims to have sacrificed many times as many—most of the families appear to be rural and not terribly well-off, and most of the ‘martyrs’ seem to have been in their early twenties or less. Most of them seem to have studied only up to the secondary or matriculation level. Only a few went to a madrassa.

Each chapter of the book consists of two parts. The first, longer, section delineates the life and character of the ‘martyr’, mostly through the words of his mother and sister, though comments from the male members of the family are not necessarily left out. Here we learn about the youth’s background, his family and his neighbourhood, his life before and after the ‘conversion,’ ending frequently with some details of his death. The second, shorter, section presents the ‘last testament’ sent home by the ‘martyr’. Stiffly formal and predictably formulaic, these statements nevertheless often reveal quite a bit about the individual mortal behind the generic ‘martyr’.

Below I give a reasonably fair translation of one complete entry from Volume I. It is quite representative of the others in tone and narration, except for one feature: the ‘martyr’ does not have a jihadi name in addition to his own. (More on names later.)

For the rest of this article, click here.

C.M. Naim is Professor Emeritus, University of Chicago