Divided We Stand: A Woman’s Word about the Iranian-American Experience

by Dagmar Riedel

Gertrude Stein is alleged to have advised young Ernest Hemingway that he’d better stick to writing postcards if he had messages for his readers. It is understandable that Iranian-Americans want to reach American-American audiences with their stories about men and women with legs astride in two different cultures. But who is authorized to question a novel with a message, if its content is certified by the author’s traditional upbringing in Iran before the Islamic Revolution?

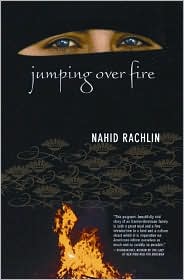

The fourth novel of Nahid Rachlin, Jumping over Fire (City Lights Books, 2005; cf. www nahidrachlin.com), has an intriguing black cover. Above the title a pair of blue eyes are staring intently at the viewer through the eye slit of a head scarf, while the bottom half merges a floral Arabesque with the yellow-red flames of a Nowruz bonfire. The title’s reference to the Nowruz purification ritual of jumping over fire is explained in the course of the novel. But on the cover the Zoroastrian tradition is presented as a variant of Western stereotypes of both the Oriental harem and Shia fanaticism because the collage promises a peek in the otherwise hidden world of a secluded Iranian woman and her burning desires. The reader has just to turn to the back cover to receive from Andre Dubus III, the son of the famous short-story author Andre Dubus, the confirmation that this is indeed a novel about a forbidden desire. The interpretation is further reinforced by the one-page biographical sketch in the back, written in the third person singular and designed to highlight in an objective language the author’s lifelong personal experience with displacement and gender-based social restrictions.

Although the paperback comes with a two-page ‘Reading Group Guide’ (pp.259-260), the publisher did not think it necessary to include a glossary of Persian words and technical terms. Some are explained by context: e.g., chadori is used for a conservative woman wearing the traditional chador; tadigh (sic) for the crusty rice that covers the ordinary Persian rice; or sofreh for the spread on which food is served. Puzzling is that the author considers it necessary to describe Friday as ‘(the Sabbath in Iran)'(p.18), because most stipulations of the Jewish Sabbath do not apply to Friday as the day of the week’s main communal prayer. Then there are words, the meaning of which cannot be derived from the context. Their explanation might have been beneficial to readers unfamiliar with Iranian culture: e.g., rupush was before the Revolution the overall coat of school children, and has since become the term for the baggy coat and cover-all that women wear as alternative to the chador; doogh is a yoghurt-based drink, similar to the Turkish variety known as ayran; dokhtar means daughter or girl; joon is a colloquial variant of jân, one of the words for soul, and can be used as term of endearment so that joon resp. joonam corresponds to the way the British use love resp. my love as a polite address.

The novel is constructed as the memoir of a woman in her late-twenties, recalling her relationship with her brother throughout their teenage years and early adolescence in Iran and in the US. In general, this is a first-person narrative, though occasionally Rachlin resorts to an all-knowing narrator to move the plot ahead (e.g., p.54). She utilizes the perspective of the daughter of an Iranian-American couple to talk about the girl’s double discrimination as woman and American in Iran and about her brother’s double discrimination as Iranian and Muslim in the US, even though she insists that this family remains fiercely non-observant in Iran and in the US. In the blurbs on the back cover, the novel is praised for its depiction of the vast cultural divide, though which divide is not specified.

Rachlin teaches writing at the New School, and thus it cannot be accidental that she uses an inversion of the classic European ‘˜voice of nature”‘ motif for this novel to illustrate the pain and suffering of an Iranian-American family. In its classic version, separately raised siblings fall in love with each other to recognize that they are kin. While the motif touches on the danger of incest, traditionally the emerging love relationship is never consummated. In Rachlin’s novel, the plot centers on the consummated love relationship between an adopted boy (Iranian-Iranian) and his sister (Iranian-American), moving from the accidental discovery of the boy’s adoption to the startling revelation that they are nonetheless siblings. While the author does not explain why there is a socio-medical infrastructure that allows a young unmarried woman to give a newborn away for adoption, the adoption itself is explained as a consequence of women’s lesser social standing. In Iran in the 1960s, it was impossible for a single woman to preserve her social reputation while raising a child born out of wedlock. But it should be remembered that being an unwed mother was at that time also accompanied with irreparable social disgrace in a Western society. In the novel, the children have the same father, an MD who works for the Iranian American Oil Company. The author suggests that this man was already torn between both cultures because he had a one-night stand, which was initiated by one of his young Muslim lab technicians, and yet nonetheless married his Irish-American fiancee, a more mature Catholic nurse. In terms of locales, it recalls Orientalist cliches that the siblings’ sexual relationship is conducted in Iran, but ceases after the family has fled to the US. At the end of the novel, the boy has returned to Iran, after completely cutting of all communication with his family in the US, and lives with his birth mother because he cannot have two mothers and two lives (p.257).

It is this solution of the boy’s predicament that feels so problematic because it puts a higher value on blood relations than on the experienced social family life. Moreover, it seems to imply that multiculturalism is not supported by human hardwiring, and in the end blood is again thicker than water. Since the late Edward Said’s seminal Orientalism, there has been a rising awareness of both racist overtones and sexual innuendo in the descriptions of Muslims and/or Middle Easterners in Western literature. So, how would have the reviewers reacted, if an American-American author had written a novel with such a conclusion? This uneasiness brings me back to my starting point. Since Rachlin is an Iranian-American woman living and working in the US, it seems difficult to challenge her personal authority on the subject. But as a novel or postcard, I would not file this book as riveting.