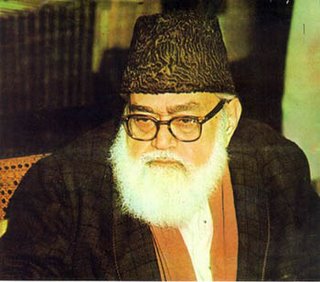

Sayyid Abul A’la Maududi (1903-1979)

By Yoginder Sikand, TwoCircles.net, May 18, 2008

The late Sayyed Abul Hasan Ali Nadwi (or Ali Miyan as he was also known) was one of the leading Indian ulema of modern times. A noted writer, he headed the famous Nadwat ul-Ulema madrasa in Lucknow from 1961 till his death in 1999. He was associated with several other Indian as well as international Islamic organisations, a mark of the high respect that he was accorded among Muslims all over the world.

Maulana Nadwi’s wrote extensively on a vast range of subjects, including on Islam and politics. On this issue, his views underwent a gradual process of change and maturation, beginning with his early association with a leading Indian Islamist formation and later making a forceful critique of some crucial aspects of its understanding of Islam. His views in this regard point to the little-known yet rich internal debate among Indian Muslim scholars about the relationship between Islam and politics, particularly on the question of what Islamists describe as an ‘Islamic state’.

In 1940, Maulana Nadwi came under the influence of Sayyid Maududi, the founder of the principal Indian Islamist outfit, the Jamaat-i Islami. Maududi, along with the Egyptian Syed Qutb, may be said to be among the pioneers of contemporary Islamism. Soon after joining the Jamaat, Maulana Nadwi was put in-charge of its activities in Lucknow. This relationship proved short-lived, however, and he left the Jamaat in 1943. He later wrote that he was disillusioned by the perception that many members of the Jamaat were going to what he called ‘extremes’ in adoring and glorifying Maududi as almost infallible, this bordering on ‘personality worship’. At the same time, he felt that many Jamaat activists believed that they had nothing at all to learn from any other scholars of Islam. He was also concerned with what he saw as a lack of personal piety in Maududi and some leading Jamaat activists and with their criticism of other Muslim groups.

Maulana Nadwi’s opposition to the Jamaat’s understanding about Islam and politics, which it shared with most other Islamist formations, comes out clearly in his Urdu book Asr-i Hazir Mai Din Ki Tahfim-o-Tashrih (‘Understanding and Explaining Religion in the Contemporary Age’) which he penned in 1978, and which won him, so he says in his introduction to its second edition published in 1980, fierce condemnation from leading members of the Jamaat. Here, Maulana Nadwi takes Maududi to task for having allegedly misinterpreted central Islamic beliefs in order to suit his own political agenda, presenting Islam, he says, as little more than a political programme. Thus, he accuses Maududi of wrongly equating the Islamic duty of ‘establishing religion’ with the setting up of an Islamic state with God as Sovereign and Law Maker. At Maududi’s hands, he says, ‘God’, ‘The Sustainer’, ‘Religion’ and ‘Worship’ have all been reduced to political concepts. In this way, Maududi, Maulana Nadwi says, sought to incorrectly suggest that Islam is simply about political power and that the relationship between God and human beings is only that between an All-Powerful King and His subjects. However, Maulana Nadwi says, this relationship is also one of ‘love’ and ‘realisation of the Truth’, which is far more comprehensive than what Maududi envisages.

Linked to Maulana Nadwi’s critique of Maududi for having allegedly reduced Islam to a mere political project was his concern that not only was such an approach a distortion of the actual import of the Quran but also that it was impractical, if not dangerous, in the Indian context. Thus, he argued, Maududi’s insistence that to accept the commands of anyone other than God, including of an elected government, was tantamount to shirk, the crime of associating others with God, as this was allegedly akin to ‘worship’, was not in keeping with the teachings of Islam. God, Maulana Nadwi wrote, had, in His wisdom, left several areas of life free for people to decide how they could govern them, within the broad limits set by the Islamic law or shariah, and guided by a concern for social welfare.

Further, Maulana Nadwi asserted that Maududi’s argument that God had sent prophets to the world charged with the mission of establishing an ‘Islamic state’ was a misreading of the Islamic concept of prophethood. The principal work of the prophets, Maulana Nadwi argued, was to preach the worship of the one God and to exhort others to do good deeds. Not all prophets were rulers. In fact, only a few of them were granted that status. Maulana Nadwi faulted Maududi for what he said was ‘debasing’ the ‘lofty’ Islamic understanding of worship to mean simply ‘training’ people as willing subjects of the Islamic state. In Maududi’s understanding of Islam, he wrote, prayer and remembrance of God are seen as simply the means to an end, the establishment of an Islamic state, whereas, Maulana Nadwi argued, the converse is true. The goal of the Islamic state is to ensure worship of God, and not the other way round. If at all worship can be said to be a means, he added, it is a means for securing the ‘will of God’ and ‘closeness to Him’.

If the ‘Islamic state’ should then simply a means for the ‘establishment of religion’ and not the ‘total religion’ or the ‘primary objective’ of Islam, it opens up the possibility of pursuing the same goals through other means. Maulana Nadwi refers to this when he says that the objective of the ‘establishment of the faith’ needs to be pursued along with ‘wisdom of the faith’, using constructive, as opposed to destructive, means. Eschewing ‘total opposition’, Muslims striving for the ‘establishment of the faith’ should, he wrote, unhesitatingly adopt peaceful means such as ‘understanding and reform’, ‘consultation’ and ‘wisdom’. Critiquing the use of uncalled for violence by some groups calling themselves ‘Islamic’, Maulana Nadwi stressed the need for ‘obedience’, ‘love’ and ‘faith’ and struggle against the ‘base self’ (nafs). Muslims should, he wrote, make use of all available legitimate spaces to pursue the cause of the ‘establishment of religion’, such as propagating their message through literature, public discussions, training volunteers, winning others over with the force of one’s own personality and establishing contacts with governments.

Maulana Nadwi’s critique of radical Islamism points to the rich theological resources contained within traditional Islamic thought that can be used to fashion alternate understandings of the relationship between Islam and politics in a far more sensible way than most Islamists have articulated hitherto and which have caused untold havoc in the name of Islam.