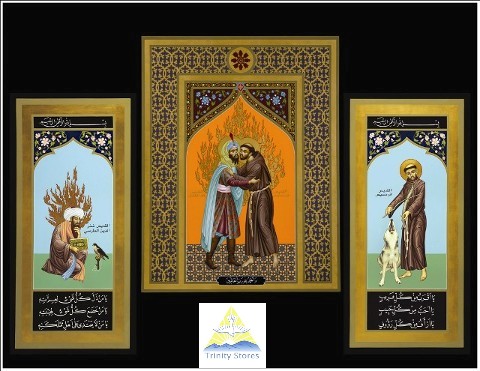

by Robert Lentz

In 1219 St. Francis and Brother Illuminato accompanied the armies of western Europe to Damietta, Egypt, during the Fifth Crusade. His desire was to speak peacefully with Muslim people about Christianity, even if it mean dying as a martyr. He tried to stop the Crusaders from attacking the Muslims at the Battle of Damietta, but failed. After the defeat of the western armies, he crossed the battle line with Brother Illuminato, was arrested and beaten by Arab soldiers, and eventually was taken to the sultan, Malek al-Kamil.

Al-Kamil was known as a kind, generous, fair ruler. He was nephew to the great Salah al-Din. At Damietta alone he offered peace to the Crusaders five times, and, according to western accounts, treated defeated Crusaders humanely. His goal was to establish a peaceful coexistence with Christians.

After an initial attempt by Francis and the sultan to convert the other, both quickly realized that the other already knew and loved God. Francis and Illuminato remained with al-Kamil and his Sufi teacher Fakhr ad-din al-Farisi for as many as twenty days, discussing prayer and the mystical life. When Francis left, al-Kamil gave him an ivory trumpet, which is still preserved in the crypt of the Basilica of San Francesco in Assisi.

This encounter, which occurred between September 1 and 26, is a paradigm for interfaith dialog in our time. Despite differences in religion, people of prayer can find common ground in their experiences of God. Dialog demands that we truly listen to the other; but, before we can listen, we must see the other as a precious human being, loved by God. There is no other path to peace in this bloody 21st century.

The flames behind Francis and the sultan have a dual symbolism. In Islamic art, holy persons are shown with balls of flame behind their heads. The second purpose of these flames is to disarm a later medieval legend in which Francis challenged the Sufis to step into a raging fire to prove whose faith was correct. In this icon, the flames represent love. The text at the bottom is from the beginning of the Koran: “Praise to God, Lord of the worlds!”

On this left-hand panel of the Peace Triptych sits Fakhr ad-Din al-Farisi, a Persian Sufi who advised Sultan Malik al-Kamil throughout his life. He was a scholar of astronomy and theology, as well as a statesman. He holds the Koran in his hand. Next to him is a falcon, tethered to a roost. It was Fakhr ad-Din who taught Frederick II how to hunt with falcons when he visited his court in Sicily–thus introducing falconry into medieval Europe. In this icon, the falcon represents restrained violence and refers to the teachings of the Koran that all Muslims must follow when they engage in warfare. While modern Muslim terrorists dishonor the Koran, Fakhr ad-Din and his sultan were exemplary men of peace who showed mercy to captives and spared non-combatants. They dreamed of peaceful co-existence between Christians and Muslims in the Middle East, even turning Jerusalem over to Frederick II, to avoid further bloodshed.

Islamic prayers fill the dark blue squares at the top and bottom of the icon. The prayer at top reads, “In the name of God, the compassionate and merciful.” At the bottom of the icon are three praises of God from the al-Jawshan al-Kabir, reflecting specific divine attributes that Fakhr ad-Din, a holy statesman, reflected in a special way:

O He before whose honor and might all things bow and obey.

O He before whose majesty all things are abased.

O our Lord, the owner of sovereignty whose subjects are safe from cruelty.

Like Christians, Muslims believe that humans mirror the glory of God–that we are images of God. Saints have cleansed the mirror of their soul so that they reflect God very brightly in our midst. The ball of flames behind the head of Fakhr ad-Din is an Islamic symbol of this reflection.

On this right-hand panel of the Peace Triptych, the fabled wolf of Gubbio represents all the frightening darkness Francis learned to embrace during his life of penance–darkness both inside and outside his heart. He is said once to have picked up two sticks to play like a violin, in a moment of ecstatic joy. The tamed wolf–still very much a wolf–is singing at his side. Francis’ face has a haunted look, rather than a more theatrical expression of joy, because we do not embrace darkness without paying a price. This expression is called joyful sorrow by Russian Christians, a joy that has not forgotten sin and all of which sin is capable.

Islamic prayers fill the dark blue squares at the top and bottom of the icon. The prayer at top reads, “In the name of God, the compassionate and merciful.” At the bottom of the icon are three praises of God from the al-Jawshan al-Kabir, reflecting specific divine attributes that Francis, the great lover, reflected in a special way:

O He who is nearer than the nearest.

O He who is more lovable than all the beloved.

O He who is more affectionate than all the affectionate.

Like Christians, Muslims believe that humans mirror the glory of God–that we are images of God. Saints have cleansed the mirror of their soul so that they reflect God very brightly in our midst. The halo around Francis’ head is a Christian symbol of this reflection.

To read more about this and purchase items with the image, click here.