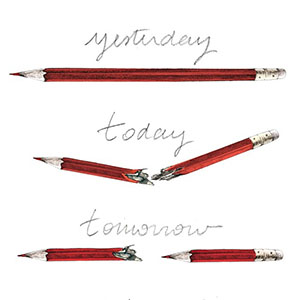

In solidarity with the people killed in Paris, this illustration is accompanied by the caption, “Break one, thousand will rise,” as part of the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag. Many people and media outlets have been sharing this illustration by Lucille Clerc but incorrectly crediting Banksy.

Credit: Lucille Clerc License: All rights reserved..

by Omid Safi, Director of Duke University’s Islamic Studies Center, On-being, January 8, 2015

As a person of faith, times like these try my soul. Times like these are precisely when we need to turn to our faith. We turn inward, not because the answers are easy, but because not turning inward is unthinkable in moments of crisis.

So let us begin, not with the cartoons at the center of the shootings at the office of Charlie Hebdo in Paris, but with the human beings. Let it always be about the human beings:

• Stéphane “Charb” Charbonnier, 47 (editor)

• Bernard Maris, 68 (economist)

• Georges Wolinski, 80 (cartoonist)

• Jean “Cabu” Cabut, 78 (cartoonist)

• Bernard “Tignous” Verlhac, 57 (cartoonist)

• Philippe Honoré, 73 (cartoonist)

• Elsa Cayat (columnist)

• Michel Renaud (a guest)

• Frederic Boisseau (building maintenance worker)

• Franck Brinsolaro, 49 (a police officer)

• Moustapha Ourrad (copy editor)… It’s not Muslims vs. cartoonists, as long as there are Muslim cartoonists.

• Ahmed Merabet, 42, (police officer)… A Muslim who died protecting the cartoonists from Muslim terrorists. Muslim vs. Muslim.

And brothers Said Kouachi and Cherif Kouachi, and Hamyd Mourad — the shooters, with a legacy of crime behind them.

I try to resist the urge to turn the victims into saintly beings, or the shooters into embodiments of evil. We are all imperfect beings, walking contradictions of selfishness and beauty. And sometimes, like the actions of the Kouachi brothers and Mourad, it results in acts of unspeakable atrocity.

So how do we process this horrific news? Let me suggest nine steps:

image

Muslim police officer Ahmed Merabet. He was shot in the head while lying on the ground begging for mercy on the streets near Charlie Hebdo’s office building.

1) Begin with grief.

We begin where we are, where our hearts are. Let us take the time to bury the dead, to mourn, and to grieve. Let us mourn that we have created a world in which such violence seems to be everyday. We mourn the eruption of violence. We mourn the fact that our children are growing up in a world where violence is so banal.

Even yesterday, on the same day of the Paris shootings, there was another terrorist attack in Yemen, one that claimed 37 lives — even though this tragedy did not attract the same level of world attention. There were no statements from presidents about the Yemen attack, no #JeSuisCharlie campaigns for them. Let us grieve, let us mourn, and let us mourn that not all lives seem to be given the same level of worth.

image

In solidarity with the people killed in Paris, this illustration is accompanied by the caption, “Break one, thousand will rise,” as part of the #JeSuisCharlie hashtag. Many people and media outlets have been sharing this illustration by Lucille Clerc but incorrectly crediting Banksy.

2) Yes, this is (partially) about freedom of speech.

Satire, especially political satire, is a time-honored tradition. Satire at its best is a political tool to invert hierarchies, to disturb and unsettle. Being unsettled and disturbed is necessary for education — education of individuals and education of communities. Unsettling is never smooth, or graceful.

Let us not make saints out of satirists, some of whom fostered racist cartoons, none of whom deserved this fate, all of whom should be mourned. Let us have the integrity to say that the killed satirists spent their lives tearing down sacred icons. Let us, in their death, not turn the satirists into the very sacred icons they opposed their whole life.

Here’s the thing about freedom of speech: There are few red lines left. In an age where almost anyone can get his/her writings published online, blocking or censoring anyone has become all but impossible. Yes, freedom of speech includes the right to offend. Yet, I wonder if our willingness to celebrate the “right to offend†also extends to us reaching out in compassion to those who are offended. I also wonder what we do when the “freedom to offend†is not applied equally across the board, but targets again and again communities that are marginalized and ostracized.

So how does one counter offensive words/images? Had the shooters in Paris actually bothered opening the Qur’an, they would have known about “repel evil with something that is lovelier.†Had they sought to embody the Qur’an, they wouldn’t have shot down cartoonists but made sure to shoot down prejudice by embodying luminous qualities that would transform the society one person at a time.

image

Pens are thrown on the ground as people hold a vigil at the Place de la Republique (Republic Square) for victims of the terrorist attack on January 7, 2015 in Paris, France. Twelve people were killed, including two police officers, after gunmen opened fire at the offices of the French satirical publication Charlie Hebdo.

Credit: Dan Kitwood License: Getty Images.

3) We do not know the political motivations of the shooters.

The healthy and spiritually sane thing to do is to pause, grieve, bury our dead, and reach out to one another. But we want explanations. We want to know why. We may even deserve to know why. Compounding the problem is that we have a cycle of 24-hour news, which has to be filled with content. It has to be filled with content even when we do not have facts available to us.

Some of the news coverage has been referring to the shooters as “Islamists.†If we define being an Islamist as someone who’s committed to establishing an Islamic state, there is no proof of that commitment on the part of the shooters. It seems more prudent to simply call them what we know they were: violent criminals.

4) Islam does not tell us the whole story. And we may not know for some time how much of the story it does tell us about.

One of the last known facts about one of the Paris shooters is that he had been involved with a scheme to join an insurgency in Iraq back in 2005. Here is how his lawyer described him:

“Kouachi, 22, lived his entire life in France and was not particularly religious… He drank, smoked pot, slept with his girlfriend and delivered pizzas for a living.â€

We have seen this pattern before, again and again: the Tsarnaev brothers were seen drinking and smoking pot; the visiting porn shops and nude bars and getting drunk. Not exactly the model of pious, observant Muslims.

There is no mythical Islam that floats above time and space. Islam is always inhabited by real life human beings. In this case, as much as in the case of 9/11 hijackers, it might be good to look more at the political grievances of the shooters than into the inspiration of some idealized model of “Islam.â€

5) Let us avoid the cliché of “satire vs. Islam.â€

Let us leave behind for one minute all the rich scholarly debate on the concept of blasphemy vis-à -vis Muslim and European civilizations. (Take a good hour to read Talal Asad’s brilliant essay on the topic.)

To portray this episode as the struggle of satire vs. Islam misses the fact that Muslims themselves have a proud legacy of political satire. In places like Iran, Turkey, and Egypt there are many journalists and satirists languishing in prisons because they have dared to speak the truth — often against autocratic and dictatorial rulers. For my own money, these are the champions of free speech, the Jon Stewarts of Muslim majority society. Bassem Youssef, who was often called the “Egyptian Jon Stewart,†is yet another example of a voice of satire who was instrumental in the Arab Spring.

6) Let’s not overdo the Muslim objection to images of the Prophet.

Yes, many Muslims today do not approve of images depicting the Prophet, or for that matter depicting Christ or Moses (also venerated as prophets by Muslims). But this was not and is not the case for all Muslims. Muslims in South Asia, Iran, Turkey and Central Asia — places that were for centuries the centers of Muslim civilizations — had a rich tradition of miniatures that depicted all the prophets, including those depicting the Prophet Muhammad. These were not rogue images, done in secret, but rather an elite art paid for and patronized by the Muslim caliphs and sultans, produced in the courts of the Muslims.

And let us give Muslims some credit. What many of them object to is not the pietistic miniatures depicting Muhammad ascending to heaven, but rather the pornographic and violent cartoons lampooning Muhammad.

image

Muslims do have a tradition of depicting Muhammad in artwork. The Mi’raj of Muhammad is a small painting from the 1700s. It shows Muhammad riding a creature called a buraq and ascending into heaven.

7) Context is not apology.

This is perhaps the most sensitive of the points. There is no point apologizing for actions that deserve no defense. The shooting of artists, satirists, journalists, heck, the shooting of any human being, is an atrocity that stands as its own condemnation.

To ask for, insist upon, and provide context, however, is part of what we are called to do. No event, no human being, no action stands alone. And even this vile action in Paris — just like the vile actions of 9/11, or the wars in Middle East — all take place in a broader context.

French Muslims are not a random collection of Muslims. They hail from Morocco, Algeria, and Tunisia, places that were colonized by the French for decades. They are, in a real sense, the children of the colonies. The traumas of the French Muslim population today are linked to and an extension of the violence inflicted by the French on Muslims colonized for decades. No empire (including the American empire) likes to be reminded of its colonial practices, but the truth must be spoken.

French society, like many other European societies, is awash in a wave of anti-immigrant xenophobia. Anti-immigration parties routinely gain about 18 percent of the vote in popular elections, and measures justified under “secularism†(including the ban on hijab in schools) target almost exclusively the Muslim minority. A Pew Global poll shows that 27 percent of all French people openly acknowledge disliking Muslims. Numbers in other European countries are even higher: 33 percent in Germany, 64 percent in Italy. Clearly, today’s Europe has a Muslim problem.

Yes, this is partially about an ideological appropriation of religion and the issues of free speech, but it is free speech as applied disproportionately against a community that is racially, religiously and socioeconomically on the margins of French — and many other European — society. As such, to purely treat this as a freedom of speech issue without also dealing with the broader issues of xenophobia is missing the mark.

I wonder in all the celebration of “freedom of expression†parades, whether we will pause to reflect on the French prohibition on Muslim women wearing the head-covering (hijab) in public schools, something that was stripped away under French commitment to secularism. I wonder why it is that all freedoms of expression are not equally valued.

A very legitimate part of the response to the crime of the shooters is to honor and proclaim the value of freedom of speech. This, indeed, must be done. And it should be done boldly and proudly. Yet there has to be an element of humility and truthfulness here as well. Consider for example the heartfelt response of Secretary Kerry to the shootings, who described them as “a larger confrontation, not between civilizations, but between civilizations itself and those who are opposed to a civilized world.â€

One has to applaud Kerry for not giving in to the tired cliché of “clash of civilizations.†Yet there is something profoundly disturbing about claiming the mantle of civilization for “us.†Doing so takes us back to the same colonial rhetoric of the 19th century that posited the world as being divided between “the civilized†West and “the savage†Rest. Let us defend the best parts of our civilizations, the ideals of freedom and liberty and equality, and let us have the integrity and honesty to also state that many people both inside and outside of our borders have often experienced Western powers as more a nightmare than a dream. For African-Americans and Native Americans in the United States, for the colonial subjects in Africa, Asia, and Latin America, the United States, France, and England have always been experiments that have often fallen short of the lofty ideals they/we proclaim. This is not to cast aspersions on the beauty of those ideals, but to always hold ourselves in check, to always remind us that the tension between being civilized and savagery is not one that divides civilizations and nations, but a tension inside each and every single one of us, each and every single one of our communities.

image

8. Muhammad’s honor.

The shooters are reported to have shouted that they were doing this to revenge the honor of the Prophet. Let me put objectivity and pretense towards scholarly distance aside. The Prophet is my life. In my heart, Muhammad’s very being is the embodied light of God in this world, and my hope for intercession in the next. And for those who think they are here to avenge the honor of the Prophet, all I can say is that he is beyond the need for revenge. Your actions do not reach him, neither did the profoundly offensive cartoons of Charlie Hebdo. That pornographic, violent, humiliated and humiliated figure depicted in Charlie Hebdo’s cartoons is not and was not ever my prophet. As for the real Muhammad, neither the cartoonists nor the shooters ever knew him. You can’t touch him. You never knew Muhammad like we know Muhammad.

And as for the shooters, they have done more to demean people’s impression of the religion of the Prophet than the cartoonists in Charlie Hebdo ever did. If the shooters wanted to do something to bring honor to the Prophet, they could begin by actually embodying the manners and ethics of the Prophet. They could start by studying his life and teachings, where they would see that Muhammad actually responded to those who had persecuted him through forgiveness and mercy.

9) So, how do we respond?

Crises try the soul of women and men, bringing to the surface both the scum and the cream. What will surface in France?

Forecasting the future is the business of fools. I will not offer forecasts, but here’s what I do hope for: I hope that it will bring out the best in French society, and not the worst. Here’s hoping that the affirmation of the values of the French republic will affirm equality, liberty, and brotherhood for all 66 million citizens, including the 5 million Muslim citizens.

One can either see the French retreating into an ideological corner, blaming a collective Muslim population for refusing to “integrate,†and blaming themselves for being “too tolerant.†In fact, eliciting that French backlash might have been one of the shooters’ goal all along, as Juan Cole has postulated. Or, one could hope that the French would respond closer to the Australians after their recent crisis, in the beautiful “I’ll ride with you†campaign.

One can hope that the response to the Paris shooting should consist of not merely a full-throated defense of freedom of speech, but also a renewed commitment to a robust and pluralistic democracy, one which encompasses marginalized communities.

Let us hope that the French response will look a lot like the response of Norway, whose prime minister Jens Stoltenberg said the following words just two days after the shooting during the memorial ceremony: “We are still shocked by what has happened, but we will never give up our values. Our response is more democracy, more openness, and more humanity… We will answer hatred with love.†Yes! More democracy, more openness, more humanity.

Let us hope that it is not merely the freedom of speech that we hold sacred, but the freedom to live a meaningful life, though others find it problematic. Let us hope that the freedom to speak, to pray, to dress as we wish, to have food in our stomach and to have a roof over our head, to live free of the menace of violence, the freedom to be human are seen as intimately intertwined… Yes, let us cherish and stand up for the dignity of the freedom of speech. And let us always remember that speech, like religion, is always embodied by human beings. And in order to honor freedom of speech, we need to honor the dignity of human beings.

May we reach out to one another in compassion

May we embrace the full humanity of all of humanity.