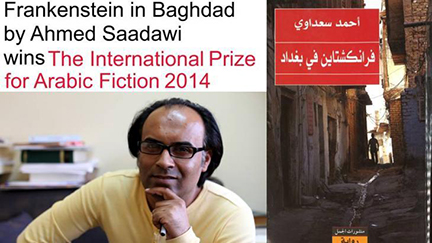

International Prize for Arabic Fiction 2014: “Frankenstein in Baghdad”

Beyond good and evil

Ahmed Saadawi’s novel “Frankenstein in Baghdad” has won the 2014 International Prize for Arabic Fiction.

Khaled Hroub presents the book, from Qantara.de

Turning the final page of Ahmed Saadawi’s novel “Frankenstein in Bagdad”, the reader’s head is full of questions: who is really the monster of Bagdad? Who created it? What does it consist of and why is it so tenacious, costing so many innocent lives? Easy, generalising answers might be: the invasion of Iraq, confessionalism, politicians and their interests …

But such banal responses simplify the situation too much, for they would mean seeing only criminals and innocents in the brutality of Iraq’s daily events.

In real life, the situation in Iraq is bitterer than any black-and-white portrayal could render. Saadawi does away with such good/evil dichotomies and counters them with a dismal reality in which simplified notions soon melt away. Neither is innocence entirely innocent, nor is crime absolute.

A monster made of severed body parts

Shesma, the monster of Baghdad, is made up of body parts of innocent victims. This new play on Frankenstein’s monster goes on a mission that initially appears clear and righteous – despite its brutality – but soon comes to seem ambivalent and sacrilegious.

Shesma wants to exact vengeance for the victims whose body parts were used to make him and hunts down their murderers and assassins. But as soon as he gets hold of one of the criminals, the body part of the person for whom he takes revenge dissolves and disappears.

A street scene in Baghdad (photo: DW/Birgit Svensson)

In his prize-winning novel, Ahmed Saadawi describes a Baghdad that has itself become a monster: “a city of segregated residential areas that are kept apart by concrete walls and checkpoints, a city at the edges of which deadly hatred between different ethnic groups flourishes,” writes Khaled Hroub

In other words, the more success Shesma has in punishing the killers, the more of him vanishes, down to whole arms and legs. However, because his campaign of revenge is not yet complete and because he wants to continue his vendetta, Shesma has to kill other people to replace the body parts that have disappeared. And so, more innocent people lose their lives.

Deadly hatred between ethnic groups

In the background of the novel, Saadawi tells the story of a lost Baghdad, a city full of life, contradictions and pain, but also a place where Muslims, Christians and Jews lived alongside each other, where Shias and Sunnis, Arabs and Kurds all breathed the air of the old town, and the people on the street were not yet divided up into denominations and religions.

He describes a Baghdad that has itself become a monster, a city of segregated residential areas that are kept apart by concrete walls and checkpoints, a city at the edges of which deadly hatred between different ethnic groups flourishes. He describes an Iraq that is like a huge prison, each floor housing a different ethnic or political group, each of which holds entirely different views to the other.

Saadawi’s allegory portrays three groups of insane individuals, who live on three storeys of the same building and keep watch on each other rather than facing up to common danger together as neighbours. The novel addresses the American occupation of Iraq, the Saddam regime and the discussion on the war: was it necessary? What was it like before? What did it bring us? Where are we heading?

These are leaden questions, turning in concentric circles in a desert barren of answers. The wonderful bygone Baghdad has transformed into a fearful and frightening, tired and tiring monster, a place with only one certainty: death. And Shesma, the man-made creature, determines the city’s wellbeing and woes.

The protagonists around the monster are also the products of its brutality. They are tired and pale, and they veer between hope for new opportunities in the new era, the assertion that everything was better in the old days and distrust of everything new.

Young children in a slum area in Baghdad (photo: DW/K. Zurutuza)

According to Khaled Hroub, the situation in Iraq is more complex and more frightening than any black-and-white portrayal could render. Ahmed Saadawi’s novel “Frankenstein in Baghdad” tells the story of a murderous, vengeful monster that haunts Baghdad and its residents

Fall from a great height

There is the old Christian woman Umm Daniel whose son never returned home from the Iran–Iraq War. Thirty years later, she still waits for him to come back. Her two daughters marry and go to Australia while she lives on the edge of insanity.

There is also General Surur, the head of the investigations department, who exploits his position to act with ruthless brutality and only serves the new powers that be with such exaggerated zeal so that they’ll forget whom he served in the past. A paid astrologer predicts terrorist attacks for the general, but confuses both him and the reader – a state falling prey to charlatanism and the dissonances of clairvoyants.

Ali Bahir Saadawi, the animated, go-getting, optimistic publisher of a magazine, maintains murky relationships and comes to a dark end, as dark as much of what succumbs to the sickness of brutalisation. Then there is the journalist Mahmud, in his mid-twenties, who moves to Baghdad from his hometown of Al-Amara and works for Saadawi. He is dazzled by fast-track success and falls, inevitably, from a treacherous peak to great depths.

Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein monster is a deadly creature of legend that has many fathers: the Iraqis and their religious denominations, terrorist organisations of all kinds, the Americans and the West, the Arabs and Iran. Each claims it is the others who are to blame for the brutality, the bloodshed and the killing, each washes his hands clean of all sin.

Shesma, however, lives among them, sleeps in their houses and looks very much like them until they finally chase him out of town. All of them hate the ugly monster, but none are willing to admit that they too had a hand in creating and protecting it.

Khaled Hroub

© Qantara.de 2014

Translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire

Editor: Aingeal Flanagan/Qantara.de