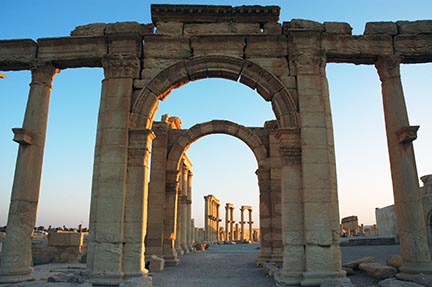

Illegal excavations and military use have recently endangered Palmyra, Syria, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Photo: UNESCO/Ron von Oers

by Shatha Almutawa, American Historical Association, April 2014

A car bomb exploded outside the Museum of Islamic Art in Cairo on January 24, 2014. The Egyptian Heritage Rescue Team arrived on the scene and began to assess the damage and prepare artifacts to be moved to another building. Trained by the International Centre for the Study of the Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property, the Egyptian volunteers worked with museum staff until all the artwork was safely relocated.

In Syria, following the destruction of the minaret at Aleppo’s Umayyad Mosque last spring, people made their way to the mosque to save the stones for later rebuilding. Some lost their lives in the process. The mosque had been used by rebels, the Syrian army was attacking from the outside, and fighting continued as volunteers worked to protect the stones. As political instability continues in the wake of the Arab Spring, cultural heritage sites and objects are often endangered.

Scholars and activists working on issues relating to the preservation of cultural heritage in the Middle East convened on February 28 at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery to discuss the Arab Spring’s impact on monuments, historic neighborhoods, and culture in the region. Lisa Ackerman, executive vice president and chief operating officer at World Monuments Fund, spoke about the importance of providing training to communities around historic sites in times of peace and after conflicts, so that locals can preserve their own heritage. She also mentioned the reality that in times of war, troops are trained to find strategic locations to use as bases; historic sites, as she explained in a later e-mail, “are often located in strategic positions with existing infrastructure, such as roads and nearby accommodations, or, as we’ve seen in Syria, are often situated at the highest points, providing a location advantage.†As an example, the US Army in Iraq chose Babylon for its Camp Alpha, which resulted in damages to its ancient walls and gates.

Heghnar Watenpaugh, an associate professor of art history at the University of California, Davis, talked about the history of Palmyra, an ancient city now used for military purposes in Syria. It had been continuously inhabited since the antique period, but when the French colonized Syria, they forcibly removed the people who lived in and around the ruins of the ancient city, and demolished their centuries-old mud-and-brick houses. Palmyra was transformed from a living city into an ancient ruin and a popular filming location for French directors. Watenpaugh addressed questions that many other speakers raised: For whom is heritage, and to whom does it belong?

Kareem Ibrahim, an Egyptian architect and urban planner who works to revitalize historic neighborhoods in Cairo, stressed that historic sites were often seen by governments as being for tourists and tourism, which resulted in attempts to evict Egyptians living near historic sites. Some parts of thriving cities were demolished in order to “sanitize†the area and provide unobstructed views of monuments. Ibrahim also pointed out that governments tend to define heritage differently from individuals. Following the fall of Mubarak’s Âgovernment, protester graffiti was painted over by the new government. Ibrahim pointed to the irony of the new government erecting a new monument commemorating the protesters of Tahrir Square, while erasing the memory already there on the walls. Heritage and cultural memory became the center of a constant fight in Tahrir Square, with one side creating its own symbols and the other erasing them. The government’s monument, with names of members of the new government on it, did not last long.

Najwa Adra and Nathalie Peutz both stressed the importance of intangible cultural heritage—poetry, tribal traditions, and social norms in Yemen. Cultural heritage is not separate from Arab Spring events. It is through poetry that people expressed their dissatisfaction, through tribal mediation traditions that they resolved differences among themselves and avoided civil war, and through their history of including women in public discourse that the leadership of the Arab Spring in Yemen is mostly female.

As fighting and protests continue, news coverage and social media do not convey a clear picture of the tapestry of events on the ground in the Middle East. ÂProtesters are intentionally and inaccurately portrayed as destroyers of cultural heritage when it is politically expedient for that point to be made. Governments are also shown as erasing cultural memory, but both sides have a hand in creating, saving, and destroying history. Nibal Muhesen, Syrian coordinator of the Danish Initiative for the Protection of Syrian Cultural Heritage under Conflict, answered my questions from Copenhagen via Facebook messages. He said that the Syrian government’s Directorate-General of Antiquities and Museums, as well as people who are not involved in politics, are documenting cultural artifacts in Syria and any damages that occur to them. The protection of cultural heritage continues in other parts of the Arab world as well.

Shatha Almutawa is associate editor of Perspectives on History.