by Ayesha Chaudhry, The Globe and Mail, March 27, 2014

Muslims have a problem with domestic violence. Let me be clear – most think it’s a terrible thing. But the troubling fact remains that it’s difficult for Muslims to argue that all forms of domestic violence are religiously prohibited. That is because a verse in our sacred scripture can be interpreted as allowing husbands to hit their wives.

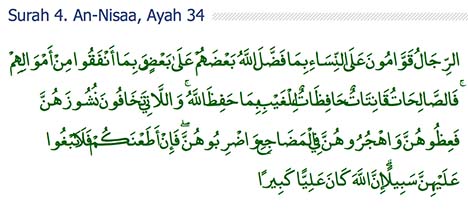

This verse, found in Chapter 4, Verse 34, has been historically understood as saying that husbands can admonish disobedient wives, abandon them in bed and even strike them physically. This verse creates a conundrum for modern Muslims who believe in gender equality and do not believe that husbands have the right to discipline their wives at all, never mind hit them. How can devout Muslims both speak out against domestic violence and be faithful to a religious text that permits wife-beating?

As it turns out, the way out of this problem lies not only in the Koran itself – but in the very verse.

Many Islamic scholars have quietly been offering compelling non-violent and non-hierarchical interpretations of 4:34 for years. One alternate reading posits that if a couple experiences marital troubles, they should first discuss the matter reasonably. If that does not resolve the problem, the couple should experiment with a trial separation. If that fails, the couple ought to separate, but if it works, then they should have makeup sex. This alternate interpretation works with the Koran’s original Arabic, which lends itself to multiple, equally valid readings.

But if it is so easy to come up with new interpretations, why have the non-violent ones not gained more widespread acceptance?

The answer lies in a key truth: Religious texts mean what their communities say they mean. Texts do not have a voice of their own. They speak only through their community of readers. So, with a community so large (1.3 billion) and so old (1,400 years), Islamic religious texts necessarily speak with many voices to reflect the varied histories and experiences of the many communities that call themselves Muslim.

The fact is that 4:34 can legitimately be read both ways – violently and non-violently, either as sanctioning violence against wives or as offering a non-violent, non-hierarchical means for resolving marital conflict. Muslims may follow whichever interpretation they choose, and the inescapable truth is that the interpretation chosen says more about the Muslim in question than it does about the verse. This marvellous agency comes with a heavy responsibility: Rather than holding 4:34 responsible for what it means, Muslims can and must hold themselves responsible for their interpretations.

Needless to say, this problem is not unique to Islam. Believers from every religious tradition rooted in patriarchal texts must find ways to reconcile evolving notions of gender equality and justice with religious traditions that were interpreted to sanction gender discrimination, social inequality and religious intolerance.

An essential characteristic of religion is that it must be made relevant to the modern day and yet remain rooted in the past; this, after all, is what gives believers a sense of belonging to a “tradition†that is longer and more permanent than themselves. So, in each attempt to bring religious beliefs in line with developing notions of justice, believers must renegotiate their relationship with a tradition that did not hold these same values.

An indispensable step in this process of reinterpretation is an honest and unflinching examination of the religious tradition. Believers need not apologize or be ashamed of their history, but they must certainly not defend and perpetuate aspects of their religious tradition that are oppressive and tyrannical.

Religious traditions are shaped by their own social and historical contexts and it’s only natural that given the evolving notions of justice and gender equality, modern Muslims will look to the Koran to protect women against gendered violence. They have begun doing so, and the rest of us, Muslims or other, must use our power to give these interpretations the authority they deserve.

Ayesha S. Chaudhry is author of the new book Domestic Violence and the Islamic Tradition. She is assistant professor of Islamic and gender studies with the Institute for Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice and the department of classical, Near Eastern and religious studies at the University of British Columbia.