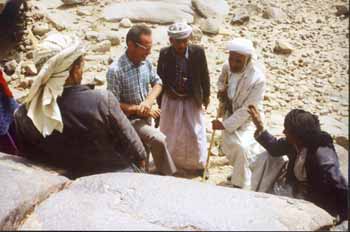

Père Etienne in Yemen

[In a previous post I commented on the life of Père Etienne Renaud, who rose to the position of leader of the Catholic White Fathers (Pères blanc), now known as the Missionaries of Africa. In 1987 he wrote a pastoral letter in the order’s in-house magazine, Petit Echo. This eloquent statement by a man who devoted his life to being a witness for humanity among Muslims and encouraging dialogue between Christians and Muslims deserves reading. It was originally written in French and translated into English in the same issue.]

Letter of Father General, Pére Etienne Renaud

Rome, 12 February 1987

Dear Fathers and Brothers,

Before taking up my pilgrim’s staff for West Africa, I should like to share some reflections with you.

After my election, several people asked me: “Is this going to change something in the Society’s commitment with regard to Islam?†One or another insisted more explicitly: “Is this going to increase our manpower in North Africa?†By way of riposte, I answered that a right wing government was well placed to make some left wing policy and vice-versa.

The fact remains that no one can make abstraction of his past, of all the missionary experience he has lived, and I must admit that my life in the Land of Islam, in North Africa as in Yemen, just as these last years teaching at the PISAI have deeply marked my general conception of mission.

My intention today, in this letter, is not to comment on the Chapter directives with regard to Islam, but to share with you some aspects of this conception of mission, which Islam has as it were forced me to deepen. I think that here it is a question of values important for every missionary, wherever he may be, even if they are values among others.

Respect for the other’s faith

In contact with Muslims, one is struck by the depth of their convictions, and more generally by the solidarity of the religious edifice of Islam. It is there, omnipresent. Study only reinforces this impression of massiveness, by helping us discover its centuries-old roots.

You realize you must take this faith of Islam into account. This can be done with the aim of combatting it and that is polemics. You can also wish to know it with the sole purpose of converting and that belongs to the expansionist strategy. Finally, you can seek to know it in order to establish a true encounter, truly human, with someone who has his own system of values. Bit by bit the conviction is thrust upon us that the first step in love is to seek to know the other as he is and he wishes to be and in particular to seek to understand his reactions, even and especially when they clash with me and provoke me.

From that, we are made aware that the dialectics of dialogue and mission, so often put forward, is a false problem. True dialogue, the one in which you are wholly committed with all that you “are†can but be witness, and hence mission. The important thing is to promote with every man a true encounter, which will be both dialogue and mission at the same time. A Tunisian Professor, Mohammed Talbi, speaks of a mutual “duty of apostolateâ€. Since the truth of the encounter implies that at the end, each one should be able to state his inmost convictions with complete frankness. It is an ideal rarely achieved, rarely possible even, but towards which we must always tend, and which proceeds through absolute respect for one’s interlocutor.

There again, it seems to me that such a step ought to have a universal dimension. And maybe the good thing about the “resistance†of Islam is that it constantly calls to our mind the presence of the “other,†that it invites us to extend our attitude of respect to the cultural and religious values of all those whom the Lord sends us, whether Muslim or not.

It is significant that the problem of inculturation is being posed so strongly now. Is this not an indication that we ought to have been more attentive to African values?

The demand of the Gospel

I spoke of the impression of solidarity which the faith of Islam gives. One can even have a feeling of imperviousness, of totalitarianism, indeed of fanaticism. It is undeniable that the rather general thrust of integralism, nourished by a political context of opposition to the former colonizers, makes still more difficult the encounter between Muslims and Christians. In sub-Saharan Africa there is in addition a feeling of bitter rivalry.

This is a fact which we can deplore. But if we deplore this hardening of Islam, it is good to remind ourselves that a good many Muslims regret it as much as we do. It is essential to remind ourselves that Islam does not have only one single face and we need to guard against making global judgments, a sign that we have few contacts with people in the concrete things of their life. Beyond those who are speaking out loud, the Gospel invites us to rejoin the men with good will.

In this we must not be naïve or nurse any illusions, underestimating the difficulties of the encounter. I believe on the contrary that we need to look them straight in the face and that irenicism does not pay. But on the other hand, let us take care not to sink into scepticism and cynicism. The Gospel invites us to remain on a knife-edge: “Wise as serpents and innocent as doves.†To be both realistic and evangelical at the same time: two words which apparently are opposed to one another, but isn’t the Gospel a realism of a higher order, the only one which lasts from the viewpoint of eternity?

And above all, we must pay tremendous attention not to let ourselves be caught by the mutual outbidding of intolerance. It seems to me that there you have something fundamentally anti-Christian. If, in the name of justice, we have to claim and defend human rights, in particular the freedom of conscience, our attitude must never be dictated by intolerance of the interlocutor, but rather by Christ’s example, who “in his flesh killed hatred.â€

And since we are mediating Christ’s example, let us nourish ourselves likewise on his desire always to go beyond, to take the first step to overflow barriers and bear witness to the universal love of the Father, throughout all tensions and contradictions.

Humility in the face of the mystery of God

The Yemenites, seeing me speak Arabic, would ask me what was my religion. I would answer them: “I am in my mother’s religion.†A most trite observation … I confess it constantly invites me to humility, as does the constant contact with another religion which also wishes to be universal.

If I am a Christian, it is because I was born into Christianity. I have not explored all the possible roads to God and made a choice in full knowledge of the facts. True, the encounter with Christ has turned my life topsy-turvy and I am convinced that He is “the Way, the Truth and the Life.†But am I sure that I have completely understood Him? Can I learn nothing from others? Who authorizes me to judge other paths which do not refer to Christ and to think that God’s Spirit cannot be present there? My experience, however chock-full it may be, does not disqualify them. It is so easy to behave as the possessor of truth. I definitely like these words of Abraham Lincoln. He had surely meditated on the parable of the Pharisee and the Publican: “Don’t be in a hurry to say that God is on our side. Let us pray to be on God’s side.â€

Living the Gospel before speaking about it, establishing a true encounter with every man in mutual respect, following Christ in his passion for reconciliation, not putting any frontiers to the mystery of God by our narrow-mindedness …, there you have some convictions which have thrust themselves upon me because of the circumstances of my missionary life…

to be continued