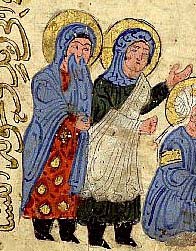

Two woman observing a conversation, Baghdad, Maqamat al-Hariri, Late Eleventh to early Twelfth Centuries, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. MS arabe 3929 fol 134, Maqamat 40, detail

Medieval Muslim Women’s Travel: Defying Distance and Dangerby Marina Tolmacheva, World History Connected

Women’s rights in Muslim societies became an especially sensitive subject of intercultural discussion in the twenty-first century. The recent Arab awakening has made understanding Islam, explaining Muslim sacred law to non-Muslims, and interpreting the internal dynamics of Islamic countries an increasingly urgent concern for educators. This paper focuses on historical evidence of Muslim women’s spatial mobility since the rise of Islam and until the early modern period, that is from the seventh until the sixteenth centuries. The Muslim accounts of travel and literature about travel created during this long period were written by men, mostly in Arabic. Muslim women did not leave behind records of their own travel, and it is only in the early modern period that some records were created by women, only a very few of which have been discovered. This means that we must rely on men’s accounts of women’s travel or draw on general descriptions of travel conditions that are applicable to women’s travel as well as men’s. Another limitation derives from the Islamic requirements of privacy and Muslim conventions of propriety: it was generally not considered good manners to discuss womenfolk or specific ladies, so medieval, and even early modern, Muslim books rarely describe living women unless it is to praise them. Historical chronicles may glorify queens, discuss important marriages made by princesses, or praise pious or learned Muslim women, but some travel books—for example, “The Book of Travels” (Safar-Nama) by the Persian traveler Nasir-i Khusraw (1004–1088)—do not speak of women at all. Some of the eyewitness evidence below explicitly related to women’s travel is drawn from the author who set the pattern of the travel account focused on pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217) and from “The Travels” (Rihla) of by Ibn Battuta (1304–1368?), who repeatedly married and divorced during his travels and sought advantage from association with prominent women met on his journeys. No such reservation was practiced in the Christian writing tradition, so occasionally observations of Muslim women on the journey may be found in the records left by European pilgrims, merchants or captives in the Near East, especially in works published after 1500.

This research draws on primary sources by Muslim authors that were mostly composed in Arabic prior to 1500. Some observations by early modern and modern European travelers are also used as appropriate. Until the age of steamship and the rail, very little changed in the conditions of travel to which Muslims were subject on a journey. Even after the Portuguese ships first appeared in the Indian Ocean in 1498 and soon after started carrying transit passengers and goods between Asian destinations, the speed of the vessel and the sailing calendar depended on the monsoon winds as they did centuries earlier. On land, caravan routes may have changed with the rise and fall of empires, but long-distance travel remained, as before, by camel. In one particular case, that of the Islamic pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj), tradition in addition to transportation played an important conservative role, so that the observations of caravan travels in Arabia (such as those by the Swiss Orientalist Burkhardt, below) are valid for contextual information about the hajj.

I have surveyed the early Arabic sources on geography and travel in the original Arabic, and edited and translated some of them in my other publications. For this paper, I selected the authoritative translations into English, broadly accessible to the reader and often used for anthologies on travel, exploration, and pilgrimage. As in early European travel writing, not all Muslim travel literature is trustworthy: fantasy and travel lore grew in various, sometimes distant cultures and spread across the Asian continent where many stories became part of the literary heritage of the wider world of Islam. While Arabic became the dominant language of Islamic religion, law, and scholarship, Islam absorbed the heritage of Persian and Indian science, and the literary traditions of Islamized Iranian, Turkish and Indian societies survived. Sometimes motifs and even stories from one tradition became part of a synthetic literary fabric of the travel lore, especially those that focused on the coastal regions of the Indian Ocean, such as the Sindbad stories of the Arabian Nights.

Islam arose in a society where travel was an everyday phenomenon. Migrations of Arabian tribes, participation in long-distance trade between the Indian ocean and the Mediterranean, regular fairs in western Arabia and the annual pagan pilgrimage to the Ka`ba in Mecca – all these occasions invited or even necessitated that men and women in the Arabian peninsula journey away from home. The transformation of the early, Arabian Islamic state into a vast empire from the seventh century CE promoted long-distance migration and settlement far beyond the peninsula. Consequent administrative and commercial expansion required communication, increased the distance of the pilgrims’ journey, and rewarded the adventure merchant. Also, within a few centuries, Islam spread among the neighboring nomads of the Middle East, Central Asia, and North Africa, incorporating these highly mobile societies into a cosmopolitan whole. Travel by Muslims extended over the whole expanse of the Islamic domain in the Dar al-Islam (Abode of Islam) and beyond, reaching into the sedentary societies of China, Indonesia, and sub-Saharan Africa.

Men traveled in this domain extensively.1 Sometimes they were accompanied by women—their wives, other relatives or slaves—but there were also women who traveled on their own. This rarely meant “alone,” however: as so many other facets of social life, travel is regulated by Islamic law, which prescribes male escorts for women and specifies what categories of males are suitable for the task. Women traveled on business, for family reasons, and to visit holy places. They were always a minority among the travelers, and not all travel was voluntary. Nevertheless, women’s presence in caravans, hostels or on shipboard was not infrequent, and treated by others as unexceptional. This attitude is implicit in the narratives of medieval and early modern observers, including legal authorities on social norm.

Elsewhere, I have explored the specific legal provisions concerning women’s travel in Islam and discussed the cases of women who refused to travel or were compelled to travel against their will2. Although they traveled extensively, Muslim women of the premodern era did not leave descriptions of their own journeys. In this paper, I use their male contemporaries’ records to discuss the actual circumstances of travel in the Muslim Middle East. Much of the information presented below goes toward explaining the reasons why travel held limited appeal to women from urban or sedentary rural societies. On the other hand, the sources partially answer the question why, this being so, they still went.3 The gleaned evidence shows that the most important journey a Muslim could perform, the pilgrimage to Mecca (hajj), was not only the most desirable travel experience for Muslim men and women, but the safest and, paradoxically, at the same time the most dangerous journey they could ever undertake.

For the rest of this article, click here.