by Corri Zoli

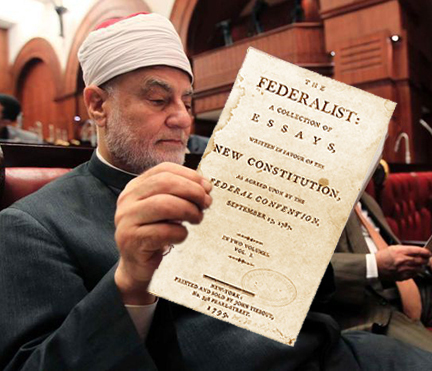

In principle, democratically elected officials can—and often do—become tyrants. It’s a fitting week in the U.S. to reread Madison’s Federalist Papers #10, which addressed both the tyranny of majorities and the more serious problem of tyranny of factions, when one group uses a democratic veneer to arrogate disproportionate power to their group’s narrow interests. When a new leader changes the nation’s constitution to serve that faction’s worldview, chances are we’re seeing factionalism in action. Recall that Madison thought factionalism the greatest threat to genuine republics and, thus, immunized young U.S. institutions (separate branches/balance of powers) to specifically thwart them.

Equally, militaries can defend and preserve democratic institutions and even aid democratic transitions. There is no question that 18th century rural colonial militias were at the vanguard of republican transition in US history. Even today in the U.S., where we operate by civilian control and where our military consistently garners some of the highest public opinion and respect, this institution routinely displays traits that protect democratic and constitutional values. One need only look at the record of who were the earliest, strongest critics of Bush-sponsored torture practices—Judge Advocate Attorneys (JAGs)—to see the professional, law-based culture of the military at work. Today, it is the signal intelligence captains—long trained to honor the 4th and never target Americans for surveillance—who are shocked by executive branch overreach in FISA decisions.

So why then are we in the US/West, evident in Western media coverage, so quick to assume that the military transition is a coup, thus, parroting the Brother’s interpretation (which certainly didn’t convince a quarter of the Egyptian population)? One answer is political formalism, which deadens good analysis: any democratically elected government some think, no matter how brutal (post-colonial Africa anyone?), is “legitimateâ€â€”forgetting Madison (not to mention Jefferson). Others’ can’t open their eyes and see that Egyptians had two solid ‘case studies’ on their borders (Islamist-governed Tunisia and Turkey) to project what their future path could be if they weren’t careful with their hard-earned revolution. Then there is Egyptian culture itself which has so much natural diversity and resilience and tolerance in ways that ideological strait-jackets don’t suit. And there was the experience of living in the last year in Egypt, watching life become a distortion of revolutionary (dignity, prosperity, inclusivity, representation) aims.

The other answer for our poverty in Egyptian analysis is simple military bias, rampant in the Western academy. Many academics think that any military is an anti-democratic institution, or some others apparently believe we are the only ones in the world that can have a professionalized, law-abiding military that isn’t constantly itching to rule the nation. The 22 million protesters—who asked Morsi first to hear their “grievances†until he predictably refused—turned to their military for a reason: they trust them and the military has proved itself to be a professional, respected, neutral institution. We should look more closely at the compromises Morsi refused in the months preceding the organized protests and his strategic use of media to incite violence when he felt his power slipping. If a military in its homeland defense role did not deal with that, they would not be worth their public investment.

While the outcome is not yet clear in Egypt, if we are smart, this event asks us to contemplate broader, more complex questions, and throws us back to rethinking our calcified certainties: do elections comprise the sum and substance of democracy? Are democratic military transitions possible and what are their conditions? How do we build power-sharing and reconciliation institutions in post-conflict settings? Can Islamists govern? and many others…

Corri Zoli is Assistant Research Professor at the Institute for National Security and Counterterrorism (INSCT), College of Law/Maxwell School of Citizenship & Public Affairs, Syracuse University