by Lauren Wolfe, The Atlantic, April 3

One day in the fall of 2012, Syrian government troops brought a young Free Syrian Army soldier’s fiancée, sisters, mother, and female neighbors to the Syrian prison in which he was being held. One by one, he said, they were raped in front of him.

The 18-year-old had been an FSA soldier for less than a month when he was picked up. Crying uncontrollably as he recounted his torture while in detention to a psychiatrist named Yassar Kanawati, he said he suffers from a spinal injury inflicted by his captors. The other men detained with him were all raped, he told the doctor. When Kanawati asked if he, too, was raped, he went silent.

Although most coverage of the Syrian civil war tends to focus on the fighting between the two sides, this war, like most, has a more insidious dimension: rape has been reportedly used widely as a tool of control, intimidation, and humiliation throughout the conflict. And its effects, while not always fatal, are creating a nation of traumatized survivors — everyone from the direct victims of the attacks to their children, who may have witnessed or been otherwise affected by what has been perpetrated on their relatives.

In September 2012, I was at the United Nations when Norwegian Foreign Minister Espen Barth Eide shook up a fluorescent-lit room of bored-looking bureaucrats by saying that what happened during the Bosnian war is “repeating itself right now in Syria.” He was referring to the rape of tens of thousands of women in that country in the 1990s.

“With every war and major conflict, as an international community we say ‘never again’ to mass rape,” said Nobel Laureate Jody Williams, who is co-chair of the International Campaign to Stop Rape & Gender Violence in Conflict. [Full disclosure: I’m on the advisory committee of the campaign.] “Yet, in Syria, as countless women are again finding the war waged on their bodies–we are again standing by and wringing our hands.”

We said after the Holocaust we’d never forget; we said it after Darfur. We probably said it after the mass rapes of Bosnia and Rwanda, but maybe that was more of a “we shouldn’t forget,” since there was so much global guilt that we just sort of sat back and let similar tragedies occur since and only came to the realization later — we forgot.

Could we have forgotten that the unfolding human catastrophe in Syria exists before it’s even over?

***

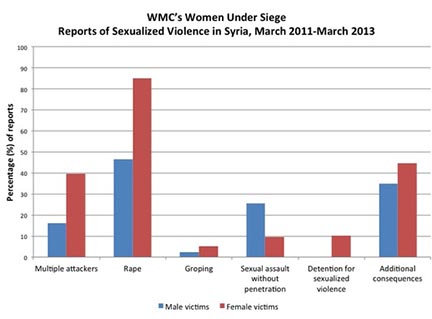

Using a crowd-sourced map for the last year, our team at the Women’s Media Center’s Women Under Siege project, together with Columbia University epidemiologists, the Syrian-American Medical Society, and Syrian activists and journalists, has documented and collected data to figure out where and how women and men are being violated in Syria’s war. And, perhaps most important, by whom.

We’ve broken down the 162 stories we’ve gathered from the onset of the conflict in March 2011 through March 2013 into 226 separate pieces of data. All our reports are currently marked “unverified” (even those that come from well-known sources like Human Rights Watch, the United Nations, and news outlet such as the BBC) because we have not yet been able to independently confirm them. Eighty percent of our reports include female victims, with ages ranging from 7 to 46. Of those women, 85 percent reported rape; 10 percent include sexual assault without penetration; and 10 percent include detention that appears to have been for the purposes of sexualized violence or enslavement for a period of longer than 24 hours. (We generally use this category when we hear soldiers describe being ordered to detain women to rape them; we’re not guessing at intent.) Gang rape allegedly occurred in 40 percent of the reports about women.

In mid-March, I was in Michigan, surrounded by Syrians who live here but are helping out their fellow citizens in refugee camps and health centers. Kanawati, the psychologist, told me that day that she had visited with a refugee family in Jordan and listened to one of three sisters describe how a group of Syrian army soldiers had come to their house in Homs, tied up their father and brother, and raped the three women in front of them. The woman cried as she went on to describe how after raping them the soldiers opened their legs and burned their vaginas with cigarettes. They allegedly told the women during this: “You want freedom? This is your freedom.”

The psychiatrist asked one of the three sisters, who was holding a baby, “Is that baby from the rape?” The woman changed the subject.

All the women are having nightmares, Kanawati said; all have PTSD. Now, she said, the two sisters are employed in Amman, but the mother, who does not work, is “consumed by the baby.” The brother will not speak.

This family is quietly living with trauma that reaches across generations.

Men are more than just witnesses to sexualized violence in Syria; they are experiencing it directly as well. Forty-three of the reports on our map – about 20 percent — involve attacks against men and boys, all of whom are between the ages of 11 and 56. Nearly half of the reports about men involve rape, while a quarter detail sexualized violence without penetration, such as shocks to the genitals. Sixteen percent of the men who have been raped in our reports were allegedly violated by multiple attackers.

Government perpetrators have allegedly committed the majority of the attacks we’ve been able to track: 60 percent of the attacks against men and women are reportedly by government forces, with another 17 percent carried out by government and shabiha (plainclothes militia) forces together. When it comes to the rape of women, government forces have allegedly carried out 54 percent these attacks; shabiha have allegedly perpetrated 20 percent; government and shabiha working together 6 percent.

Overall, the FSA has allegedly carried out less than 1 percent of the sexualized attacks in our total reports. About 15 percent of the attacks have unknown or other perpetrators.

When it comes to men, more than 90 percent of the reports of sexualized violence have been allegedly perpetrated by government forces, which can perhaps be explained by the fact that most of these attacks occurred in detention facilities. Long used as a weapon against prisoners in Syria as in much of the world, rape appears to be utilized during this conflict in horrifyingly soul-crushing, creative ways. Beyond simply raping detainees, shabiha members or Syrian army soldiers have reportedly carried out the rapes of family members or other women front of prisoners.

Atrocities are inevitably muted when victims die, and perpetrators worldwide know this. Part of the reason we’ve chosen to live-track sexualized violence in Syria is because so much evidence is lost in war. Consider that 18 percent of the women in our reports were allegedly witnessed killed or found dead after sexualized violence. Look at this report from Beirut-based news site Ya Libnan, which describes a confession from a defected Syrian Army soldier who said he was ordered “to rape teenage girls in Homs at the end of last year.”

“The girls would generally be shot when everyone had finished,” the soldier said. “They wanted it to be known in the neighborhoods that the girls had been raped, but they didn’t want the girls to survive and be able to identify them later.”

Because there is a deleterious and under-documented personal aftermath of sexualized violence, we are also tracking its mental and physical health fallout. Ten percent of the women in our reports appear to suffer from anxiety, depression, or other psychological trauma, and that’s clearly a low estimate considering the acts described. Three percent of the women have reportedly become pregnant from rape, and 2 percent suffer from a chronic physical disease as a result of the violence.

***

When I asked Kanawati how many women she’s spoken to and treated who have survived rape, she said it’s impossible to know. She has interviewed dozens of refugees who may have been raped or otherwise sexually tortured, mostly in Homs. Originally from Damascus, she is currently the medical director of Family Intervention Specialists in the Atlanta area and has been working with Syrian refugees in Amman with the support of the Syrian-American Medical Society.

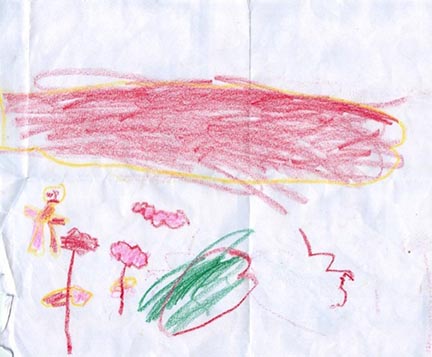

A 4-year-old girl from Homs drew this for a psychiatrist in Amman. The girl had witnessed her uncle killed by a tank, and kept repeating “Uncle, tank, blood,” according to the psychiatrist. The girl’s mother says their neighbor was raped by Syrian soldiers the same day. (Yassar Kanawati)

“Syrian families are very conservative and I always tell them: ‘ Rape is a way to break the family. The easiest way,'” Kanawati said. “I tell them, ‘Don’t let this break you–this is what they’re trying to do.’ When I tell that to the women, however, they say, ‘Tell that to our husbands.'”

She described how women have repeatedly told her that their neighbors were raped, usually by more than one man, and how each time the extraordinary detail the women give and the trauma they exhibit tells her that the story isn’t actually about a “neighbor,” but the woman herself. More than that, the storytellers usually go on to describe how the “neighbor’s” husband then left this woman.

Sex outside of marriage, let alone the violation of a woman in an act of rape, said Kanawati, is “completely taboo.”

Erin Gallagher, a former investigator of sexual and gender-based violence for the UN’s Commission of Inquiry on Syria (and before that on Libya), spent months speaking with Syrian women and men in camps in Jordan and Turkey. She said it’s very difficult to get an accurate idea at this point of the scope of sexualized crimes in Syria and that “there are more victims out there than what we are finding.” Getting a true idea of the scope, she said, “is going to take time, trust building, and a broader, holistic approach.”

Kanawati said her sister, an ob-gyn who lives in Damascus, has carefully told her (for fear of eavesdropping), “You would not believe how much rape there is.” Her sister has treated women who say they have been raped by soldiers or shabiha militia members in the rural areas around the city.

Gallagher explained why so few victims of sexualized violence in Syria are coming forward publicly.

“The reality is that they have much to lose and little to gain by doing so at this point in time, for many reasons,” she said. “It takes a lot of courage and strength for a victim to speak up and they may be on their own with little support as they do it. In addition to the shame and isolation a victim may feel, they now are in an insecure environment due to the war. They may now be living in a large refugee camp with no privacy, surrounded by people they don’t know or trust.”

With no clear future for Syria in sight, refugees are understandably cautious about who they speak to and trust with sensitive and personal information. “If they tell someone, to whom and where does that information go?” Gallagher said. It may be hard to put their trust in a stranger when, time and again, there has been little justice for victims of wartime rape.

Add to all that the physical, psychological, and emotional trauma that victims are suffering from the war and displacement, and “it’s not surprising that victims are reluctant to come forward,” she said.

Hearing this I can’t help but think of the preface to Night, in which Elie Wiesel writes: “For the survivor who chooses to testify, it is clear: his duty is to bear witness for the dead and the living… .To forget would be not only dangerous but offensive.”

***

“The security forces and the shabiha took whole families outside after destroying their homes,” a woman named Amal told the pan-Arab newspaper Al-Hayat in June 2012. “They stripped my girls from their clothes, raped them then killed them with knives. They were shouting: ‘You want freedom? This is the best brand of freedom.'”

It’s nearly word-for-word the sentences spoken in the story above about the women raped and then burned with cigarettes.

Coincidence? Maybe. But repeated phrasing is exactly the kind of thing that helps build international cases for human rights violations. Language can indicate whether mass rape has been coordinated and systematic. Recently, a U.S.-based group called AIDS-Free World successfully petitioned to have South Africa investigate mass rape allegedly carried out by the ruling ZANU-PF party in Zimbabwe against opposition supporters in 2008. Part of their case was built on the fact that they heard that similar phrases were being uttered during rapes across the country–women were called “traitors to Zimbabwe” or told they were being “sent a message,” according to Paula Donovan, co-director of AIDS-Free World.

Gallagher, who also investigated rape in Libya, said she’s heard about such phrases being used during rape in both countries.

“I don’t think it necessarily means it was an order,” she said of Libya, “but certainly a common belief among the soldiers. They knew they had free reign. I can’t conclude if [Bashar al-] Assad and his command ordered it or have just given his men free reign. What is clear is that he and his commanders are doing nothing to stop their soldiers from committing such crimes.”

For a year, I’ve sat in circles of high-level advisors from the International Criminal Court and elsewhere debating what might tip Russia’s hand and prevent it from vetoing a vote to send Syria’s human rights crimes to the court. But now with the success of AIDS-Free World’s use of a concept called universal jurisdiction, which crosses borders to try crimes that are so heinous that they call for a sense of greater justice, perhaps it is time to consider alternatives to the ICC. Jody Williams, known for rousing the slumbering world when it came to banning landmines, has some ideas.

“We don’t need more research or more proof, we need a plan,” said Williams. “And the plan should be to ensure that there is coordinated international action to ensure survivors get help, justice is served against those perpetrating the sexualized violence, and we are all working together to prevent further rape. This will take men, women, communities, national governments, and the international community–everyone.”

Personally, I’m hoping this is the last report I’ll have to write parsing data from a map that shouldn’t have to exist in the first place. Somehow, though, I don’t think that will be the case.

For the charts and all the hyperlinks that come with the article, go to the original website at The Atlantic.

Lauren Wolfe is the director of Women Under Siege, a Women’s Media Center initiative on sexualized violence in conflict. Wolfe is a former senior editor at the Committee to Protect Journalists. She writes regularly at laurenmwolfe.com.