By Jane Dammen McAuliffe

Dean of Arts and Sciences, Georgetown University

Professor, Department of Arabic and History

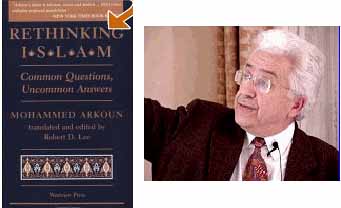

Mohammed Arkoun is the most honored French Islamicist alive today and continues to receive lecture invitations from around the world. His first language was Berber, and he learned Arabic and studied Islamic sources in French-speaking schools, first in Algeria and then in Paris (Gunther:127-131). Arkoun’s life-long project has been the sustained analysis of Islamic reason from the perspective of the contemporary epistemologies, both philosophical and social scientific. He is well-schooled in the successive forms of critical theory that have occupied humanistic scholarship for the last generation, particularly structural linguistics and semiotics. About twenty years ago Arkoun published a book of his essays on the Qur’an, and true to his formation as a medievalist, he began by situating his work in relation to the cumulative and comprehensive encyclopedia of the “qur’anic sciences†produced at the end of the fifteenth century by Jalal al Din al Suyuti (d. 911/1505). Arkoun demonstrated through his juxtaposition of this work with that being done in the twentieth century, by both Muslim and western (i.e., non-Muslim) scholars, how binding has been the fixation and circumscription of qur’anic discourse, how powerfully “dogmatic enclosure†(cloture dogmatique)-to use his term-has operated. What stands within the enclosure is “thinkableâ€; what falls outside it is the “unthinkable†(impensable). Part of Arkoun’s project is to rescue those strands of thought, both past and present, that have been unreflectively relegated to this latter category. His is a hermeneutic of retrieval bound together with a reconceptualization of the qur’anic event through the lenses of contemporary humanistic and social sciences scholarship.

A comfortable acquaintance with cultural anthropology, for example, allows him to be sensitive to dimensions of the qur’anic experience that have only recently become the focus of scholarly attention. Many years ago I stumbled over a statement, actually an aside that he had buried in a footnote: “One cannot insist too strongly on the importance of the assimilation, through force of ritual repetition, of the rhythmic structure, of the affective and aesthetic charge, of the semantic contents (for those who understand Arabic) of the Qur’an. This is what makes it so different for the practicing Muslim to create the intellectual distance that makes objects of analysis out of these assimilations†(Arkoun 1982:x). This comment succinctly captures my efforts earlier in this address to insist upon the phenomenological singularity of the “experienced Qur’an.â€

Arkoun’s writings are richly evocative and insightful but not systematic. He resists systematizations just as he resists orthodoxies, whether they be theological or academic. Of the scholars whom I am presenting to you, Arkoun is the most self-consciously aware of the relation between Muslim and non-Muslim or “Orientalist†scholarship on the Qur’an. For years he has taken his non-Muslim colleagues, including this speaker, to task for what he deems their complicity with the controlling orthodoxy of politically supported Islam. In a recent contribution to the Encyclopedia of the Qur’an, Arkoun argued that the reluctance of non-Muslim Islamicists to operate as theologians and exegetes with Muslims texts constitutes a false courtesy that undermines the efforts of their Muslim colleagues and supports self-justifying orthodoxies (Arkoun 2001: 417-418). Not only does he urge and encourage such work, he also situates the activity of scriptural hermeneutics, be it biblical or qur’anic, in a cross-traditional context. Arkoun speaks often of the “Societies of the Book,†meaning those cultures whose religious imaginaire has been decisively shaped by a vertical notion of revelation. He argues that a comparative hermeneutics will more clearly demonstrate the historicization of revelation, the different modalities within a particular cultural tradition. In an article published by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies at Georgetown University, Arkoun demonstrates how the qur’anic experience (in its relation between the umm al-kitab and the mushaf) can function as the primary exemplar for this comparative effort (Arkoun 1987:14-18).

Presidential Address for AAR in 2004, published in Journal of the American Academy of Religion 73(3):625-627, 2005.