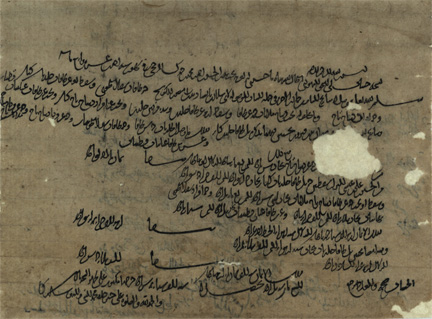

A document attesting to the accounts of Abu Ishaq the Jew (1020-1021CE); The National Library of Israel

By Isabel Kershner, The New York Times, January 14, 2013

JERUSALEM — A batch of 1,000-year-old manuscripts from the mountainous northern reaches of war-torn Afghanistan, reportedly found in a cave inhabited by foxes, has revealed previously unknown details about the cultural, economic and religious life of a thriving but little understood Jewish society in a Persian part of the Muslim empire of the 11th century.

The texts are known collectively as the Afghan Geniza, a Hebrew term for a repository of sacred texts and objects.

The 29 paper pages, now encased in clear plastic and unveiled here this month at the National Library of Israel, are part of a trove of hundreds of documents discovered in the cave whose existence had been known for several years, with photographs circulating among experts. Remarkably well preserved, apparently because of the dry conditions there, the majority of the documents are now said to be in the hands of private dealers in Britain, Switzerland, and possibly the United States and the Middle East.

“This is the first time that we have actual physical evidence of the Jewish life and culture within the Iranian culture of the 11th century,†said Prof. Haggai Ben-Shammai, the library’s academic director. While other historical sources have pointed to the existence of Jewish communities in that area in the early Middle Ages, he said, the documents offer “proof that they were there.â€

The texts are known collectively as the Afghan Geniza, a Hebrew term for a repository of sacred texts and objects. They were written in Hebrew, Aramaic, Judeo-Persian, Judeo-Arabic and Arabic, and some used the Babylonian system for vowels, a linguistic assortment that scholars said would have been nearly impossible to forge.

One text includes a discussion of Hebrew words that are spelled the same but have different meanings. Another is a letter between two brothers in which one denied rumors that he was no longer an observant Jew. There are legal and economic documents, some signed by witnesses, recording commercial transactions and debts between Jews and their Muslim neighbors, and other mundane yet illuminating details of daily life like travel plans.

One missive between two Jews, Sheik Abu Nasser Ahmed ibn Daniel and Musa ibn Ishak, dealing with family matters, was written in the Hebrew letters of Judeo-Persian, but had an address in Arabic script on the back, presumably for the benefit of the Muslim messenger. One document has a date from the Islamic calendar corresponding to the year 1006.

The most important religious text among those acquired by the National Library is a fragment of a Judeo-Persian version of a commentary on the Book of Isaiah originally written by the renowned Babylonian rabbinic scholar Saadia Gaon, a previously unknown text. A sliver of it has been sent to the Weizmann Institute of Science in Rehovot for carbon dating.

The exact source of the documents is murky. The manuscripts are said to have come from a remote area near the borders of Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, wild terrain largely controlled by warlords. Jews probably migrated there in the early Middle Ages to engage in commerce along the Silk Road, the important trade route linking China and Europe.

Scholars say the texts were probably found several years ago and have been sold and scattered around the globe. An Israeli antiquities dealer obtained 29 of the texts and, after a year of negotiation, sold them several weeks ago to the library for an undisclosed sum.

People involved in the purchase refused to give exact details, but they said the library ended up paying an affordable price of several thousand dollars per text. Professor Ben-Shammai said that despite the “very exaggerated prices†demanded by dealers abroad, the Jerusalem dealer did not want the documents to end up in private hands.

The National Library would like to gather the entire collection under one roof, but the current asking prices for the remaining texts add up to many millions of dollars.

Prof. Shaul Shaked, an expert in Iranian culture at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, said that dealers abroad had asked his opinion of the documents, and that he was one of the first who recognized their importance. “So in a way I am guilty of having driven up the prices,†he said.

Aviad Stollman, the curator of the library’s Judaica collection, said that the library was looking for a donor to buy the rest of the collection.

The acquisition comes as the National Library is in the midst of transformation, separating from a merger with Hebrew University, moving off campus and digitizing its vast collection. Founded in 1892 with the goal of gathering the intellectual heirlooms of a widely dispersed Jewish people, the library counts among its prized possessions two volumes of Maimonides’s Commentary on the Mishna, Isaac Newton’s manuscripts, a 15th-century Persian Koran illuminated in gold and lapis lazuli, and a notebook in which Franz Kafka practiced Hebrew vocabulary.

The 29 Afghan pages will join those texts and, once scanned, complete their journey from a dark cave to the glow of the world’s computer screens. The goal is to build a digital platform that would make the manuscripts widely accessible, with translations and explanations available online.

“This tells the story of the Jewish people,†Mr. Stollman said. “The technology is here. You can make it come alive.â€