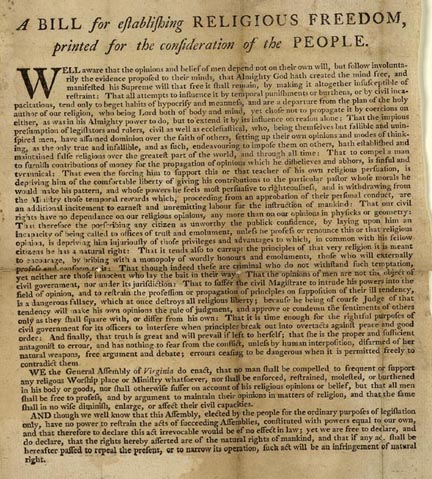

Virginia Bill for Establishing Religious Freedom; source, Library of Congress

By Anouar Majid, Tingis Redux, January 8th, 2013

The deeply contentious referendum on Egypt’s new constitution last December 2012 gave me some hope that not all is lost to Arabs and Muslims in the aftermath of the revolutions that toppled dictators in the last two years. Given the rapid Islamization of the public sphere in much of the Arab world in the last few decades, I was expecting something close to a landslide, not a small voter turnout and a modest 63.8 percent in favor of the charter. As it turns out, there are still pockets of resistance that oppose the Muslim Brothers and their agenda, even though, as the New York Times columnist Thomas Friedman noted at that time, the divisions are not necessarily between Islamists and secular liberals. The fault lines in Egypt seem to be more varied than what is broadcast in the United States.

Be that as it may, the thing that concerns me the most is what the Western media is talking about, i.e., the clash between those who want a nation governed by divine law and those who don’t want religion to be the absolute reference in legislation. In November 2012, I had the opportunity to make the case for the separation of state and religion to people who participated or are actually participating in the drafting of constitutions in Morocco and Tunisia, a person who ran in the last presidential race in Egypt, members of the Tunisian parliament, a leader of a major Egyptian political party, and many others who are playing some role in the future of North Africa and the Middle East. I also explained why, at this crucial juncture in the region, Arabs and Muslims can’t do better than learn from the American constitutional process and especially the reasons for separating state and religion.

Fewer documents explain more powerfully the reasons for doing so than the Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom, first written by Thomas Jefferson in 1777–only a year after he drafted the Declaration of Independence–and enacted into law in January 1786, with the crucial help of James Madison. Jefferson was so proud of Virginia’s Religious Act that he wanted it noted on his epitaph.

The Religious Freedom Act starts with the premise that God has created the mind free and that all attempts to enchain it are violations of the divine plan. As Muslims well know from the Koran, if God wanted to make everyone the same, He would have done so. Coercing people into an official faith “has established and maintained false religions over the greatest part of the world and through all time,” the act states when explaining why politicians should remain as far away as they could get from people’s conscience. “Our civil rights,” Virginia’s lawmakers agreed, “have no dependence on our religious opinions” and public office could be held by any citizen, regardless of his or her beliefs. Truth emerges out of debate and discussions, not compulsion. And so the lawmakers concluded: “Be it enacted by General Assembly that no man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer on account of his religious opinions or belief, but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of Religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge or affect their civil capacities.”

Virginia’s Religious Freedom Act was reflected in Article V of the U.S. Constitution which states that “no religious Test shall ever be required as a Qualification to any Office or public Trust under the United States.†It also inspired the First Amendment of the Bill of Rights that was attached to the final draft of the Constitution: “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.†As late as 1947, the Supreme Court saw it fit to restate the principle when it wrote: “Neither a state nor the federal government can set up a church. Neither can pass laws which aid one religion, aid all religions, or prefer one religion over another. Neither can force . . . a person to go to or to remain away from church against his will, or force him to profess a belief or disbelief in any religion.â€

When the founders of the United States met in Philadelphia in 1787, the thirteen colonies had behind them not only a collective 150 years of experience in constitution writing and self-government, but also centuries of English law working on separating the powers and protecting liberties, and, for some founders, an excellent knowledge of ancient Greek and Roman history. The constitution that emerged a few months later–the oldest written national constitution in the world–was the end result of a long tradition and a profound knowledge of the classics. That Arabs could think of working out their constitutional issues without being aware of this American experience strikes me as shortsighted and self-defeating.

The new Egyptian constitution is proof that Arabs and Muslims badly need to examine the American constitutional experience and use a writer like Jefferson to trim down rhetorical excesses. After congratulating itself for its greatness and leadership of Arabs and Muslims in the preamble, the Egyptian charter enshrines the sharia as the source of laws. (As in medieval Islam, Copts are to be self-governed in their religious affairs.) The Al-Azhar (a sort of Vatican of Sunni Islam) is entrusted with the arbitration of religious matters by ensuring its political and financial independence. The freedom of monotheistic religions is guaranteed, as are the general freedoms of Egyptians, provided they don’t violate Egypt’s traditions and Islamic principles. Thus, the medieval cultural foundations of Egypt are left undisturbed. The short American Constitution drafted in the 18th century is far more modern than the lengthy Egyptian one drafted in the 21st, even though the latter has some interesting progressive provisions on the rights of inmates and children.

By protecting freedom of conscience and opinion, America’s founders were betting on the powers of the unconstrained human mind, not on some mineral resource buried in the ground. The experience worked. The thirteen colonies grew into a mighty superpower that is still defining the destiny of the world. To be sure, the American experience was not without its problems and challenges. But the American Constitution unleashed a powerful drive for freedom, one that has led to the dismantling of many oppressive structures, the election of a black man and the son of an African immigrant to the presidency, and an endless process of invention and re-invention. Religious Americans are still happily devout in their churches, temples, mosques and other places of worship and assembly. Their organizations are even exempt from taxes. Those without religion—the “Nonesâ€â€”are growing by the day. All are given equal protection and rights by the law.

Arabs have the right to disagree with the United States, but when it comes to enshrining a culture of freedom in their societies, the American experience is a far better example than anything they can find in their history.

About the Author: Anouar Majid is Director of the Center for Global Humanities and Associate Provost for Global Initiatives at the University of New England in Maine, USA. He has written many books and articles on the West, Islam, and the clash of ideologies in the modern world. Majid is also a novelist, the author of Si Yussef (1992, 2005).