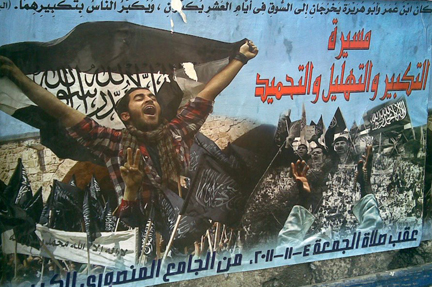

Poster in Tripoli, Lebanon; photography by Estella Carpi

Unearthing a misconceived “normalization†of violence in Beirut. The October car bomb in relation to generalized insecurity.

The 19th October 2012 car bomb in Beirut’s Ashrafiyye, within the Eastern district of the Lebanese capital, shed light on the re-articulation of the relations between the State, allegedly “inexistent†in the Lebanese context, and its society that lives in the constant effort to subjectively reformulate their citizenship, in the lack of a commonly shared nationhood.

New outbursts of violence seem to give a reason to the state to promote its technology of control, as Michel Foucault would put it. This complex re-articulation of relations has come to the fore with the October 26 White March from Martyrs Square (Beirut Downtown) to Sassine Square (Ashrafiyye, where the explosion was one week before). The “White Marchâ€, in which no political flag but the national Lebanese was waved, wanted to be considered as an act of social refusal of further violence and national solidarity, in addition to their political contestation of both the 14 and 8 March coalitions, which have politically and socially polarized the country into two sections after Hariri’s murder in February 2005. The White March mainly had the implicit aim of contesting the taken for granted watershed between what is “normal†and what is not in Lebanese parameters.

Social fear, as well as the perception of risk in Beirut, has specific historical explanations. Lebanese society seems to be doomed to live in a not-war-not-peace state, as Jeffrey Sluka used to define Northern Ireland during the clashes between Protestants and Catholics. Such an unstable state has engendered a social attitude towards violence that has been named by political scientists and journalists as “normalizationâ€, which, in light of the Lebanese reaction to the last explosion, begs for a re-conceptualization.

The reluctance to admit that instability might increase, and the goliardic will of kidding about violence outbursts and of guessing about what will be next on the other hand, are both part of the same scenario. This is imbued with public exorcizing of individual fear and controversial familiarization with war. It is in this sense that Mahmud, 31 years old, from the Southern Suburbs of Beirut, told me six months ago that sometimes war becomes an opportunity: “My only way of positivizing something that will happen, even though not deliberated, it’s to think of it as a resetting space where you can really do whatever you like, since war generates a real state of chaosâ€.

Fear is rarely dealt with in the official public arena, and this is due to the way of maintaining social balance between the parts by hiding power relations. Such a balance can be maintained, in some cases, through re-distribution of insecurity: in this case by involving the eastern district of Ashrafiyye, an area of Beirut that, on a whole, is conceived more stable nowadays than the southern suburbs.

The importance of making the representational picture of Lebanese fearlessness emerge is able to bury the real phenomenological experience of people that inhabit the hurt public space. The quick renormalization of urban spaces can be found in the feeling of “human betrayal†that one might have while passing by Martyrs Square after Sunday 21st October clashes, and seeing that the martyrized space seems to have fallen into oblivion in its unresolved suffering.

Although the killing of Wissam al Hassan may eventually expand the jurisdiction of the Special Tribunal for Lebanon (STL) in the near future – still investigating on Hariri’s murder – the public perception and responsiveness to the latest assassination is highly different, and not merely due to the different role al Hassan was covering in the political scenario. Lebanese society has often expressed rejection of the 2005 March polarization through which any social fact is constantly interpreted – as also the current events in Syria.

Nonetheless, the external perception of violence in Lebanon, owing to the large media coverage and its representation of risk, ends up clouding the daily dimension of Lebanon’s open wounds and scars, to which the everyday predicament of most Sudanese, Iraqi and Palestinians refugees contributes, as well as the silenced detention life of Asian and African workers, basically enslaved by the classist system and constituting the most recent emblem of Lebanese frightening inequality. The widespread rhetoric of the Lebanese failing state has also domestically produced the same disguising effect as the international media.

Whereas the presence of military forces is synonymous with insecurity, potential risk and readiness for war in the foreigner’s viewpoint, it becomes instead absence of violence and warrant of stability and control from an inner perspective. The chronic presence of security forces merely makes visible further what is tacit on a public level: so to speak, the incubation of revenge plans and assassination circles, still able to vent their atrocity many years later (for example, I refer here to François al Hajj’s assassination in December 2007 as he was leading the Lebanese forces in Nahr al Bared camp in the June 2007 battle against Fatah al Islam, or, again, Elie Hobeika, assassinated in 2002 as he was one of those responsible for the Sabra and Shatila massacres in September 1982).

Widely shared fear in the Beiruti public space would generate fertile soil for what Rebotier calls “meta-narrative†of urbanity in the case of Venezuela. I would recycle differently his expression to indicate that a meta-narrative of social insecurity (that is to say a verbal space of individual expression of insecurity) would therefore unearth the several social misdeeds, usually ignored in the media coverage. Such a meta-narrative would have the potential, to my mind, to legitimate public sharing of individual fears, raise awareness in all Lebanese strata, and particularly enhance mutual understanding, the lack of which is too often attributed to the unfathomable culturalization and ethnicization of needs and demands in such a variegated context.

The potentiality of being a victim anytime and anywhere, regardless of one’s social and confessional affiliation or hierarchical status, temporarily leads to the de-politicization of social fear despite the subsequent social redefinition of scapegoats. In other words, while the assassination of al Hassan has merely aimed at killing the victim, it has temporarily de-politicized social fear. Even so, interpretations of the accident as an attempt to draw Christian parties into the ongoing disorders have not missed – since the explosion took place in one of the predominantly Christian districts of Beirut. For the most apocalyptical, even the menace of a new civil war can be perceived. On the contrary, clashes and disorders between Shiites and Sunnis in Tariq el Jadide and Cola Station in the Western part of Beirut do not generally generate the same public reaction among all social strata.

Social cohesion, in such circumstances, lies in the inexistent “golden age†that Lebanon has never experienced since its creation in 1920, with the beginning of the French mandate (al Intidab al Faransy). As such, social cohesion has always been epitomizing a mere ideal tension throughout the years. My personal considerations unluckily contribute to reifying Beirut as a space of hopelessness, and as the last straw of an intellectual proliferation on Lebanese “incurable woundsâ€. In order to emerge as a renewed social space, individual fears, on the one hand, should be overtly tackled and catharsis from fear discussed; on the other, catharsis itself must not be necessarily conceived as homogeneous and unanimous.

Thus, what has been generally meant by “normalization†is sometimes misconceived, as imagined in terms of social indifference towards violence outbursts or, yet, thought of as lack of “real†suffering, as though the suffering body needed to provide evidence to be accepted as such. “Every health care entity has addressed our psychological fears and our everyday disturbs as though it merely were a bomb in the 2006 war that made a difference in the miserable life we used to lead in South Lebanon until 2000â€, a friend from Tyre says to me. In addition to the liberation from the Western hegemonic conception of fear, therefore, it is a real space of mutual recognition of fear and social denunciation that still lacks in Lebanon. The “territorial life†many Lebanese still tend to lead signals the common idea that security pragmatically means moving in an area that culturally, sometimes politically – and religiously in complex ways – represents them. In this sense, insecurity is exclusively produced by external factors, such as the arbitrary belief that Syrian refugees are the “new night sexual harassers†in Beirut s Eastern districts.

In a different way, the concept of normalization itself can entail, as a matter of fact, a “constant state of fear†– in Hebrew “sh’lo yarimu roshâ€, in which, for instance, Israelis keep Palestinians in the occupied territories on a daily basis.

In the case of Lebanon, the phenomenology of fear described above basically lies in the fact that inequality, inseparable cause and product of insecurity altogether, is never openly questioned and even blurred by more blatant acts of violence, such as a car bomb.

Estella Carpi is a PhD Candidate at the University of Sydney and PhD Fellow at the American University of Beirut.