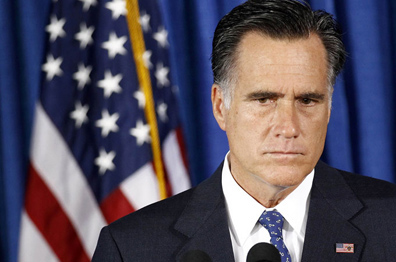

US Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney listens to questions on the attack on the US consulate in Libya, in Jacksonville, Florida, September 12, 2012. [Reuters]

Romney poses, as militants burn a US consulate over Islamophobic film

By Juan Cole, Al Jazeera, September 14, 2012

As Mitt Romney misfires on the campaign trail; scholar argues that the events in Benghazi are atypical of the new Libya.

Predictably, Republican presidential candidate Mitt Romney tried to make political hay of the tiny demonstrations in Cairo and Benghazi by Muslim militants. The Benghazi mob turned violent in clashes with police and the consulate ended up being burned and an embassy staffers being killed.

Romney seized on the frantic tweets of the Cairo embassy, which condemned the sleazy Youtube videos by American Islamophobes that had provoked the ire of the crowds, as evidence that the Obama administration was sidingwith the attacking mobs. First of all, really? Romney is trying to get elected on the back of a dead US diplomat? Second of all, really? He thinks the State Department thought the attack on themselves was justified? Third of all, really? Romney is selective. When it comes to Christianity, Romney decries a ‘war on religion.’ But apparently he thinks there *should* be a war on Islamic religion. Romney’s intervention (he is just a civilian at the moment) in American foreign policy is unwise and risky, not to mention distasteful.

The victory in the Libyan elections of nationalist rather than fundamentalist forces, and the rise to power in Egypt of the relatively moderate Muslim Brotherhood has marginalised the militant strain of Muslim activism, known colloquially as ‘jihadis’ because of their emphasis on vigilante violence. The vigilante fundamentalists were small but dangerous groups in Muammar Qaddafi’s Libya and in Hosni Mubarak’s Egypt, and both governments reacted by attacking them and arbitrarily imprisoning them.

Placing the events in context

The vigilante fundamentalists typically reject elections and democracy, as inauthentic Western imports, and they are headline whores, plotting out attention-grabbing mob actions. These jihadis are tiny groups in Egypt and Libya, though sometimes well-armed and well-trained.

You could make an analogy to the Ku Klux Klan in the United States, which just has perhaps 5,000 active members. But people like Wade Michael Page, who had applied for Klan membership, can make a media splash by simply shooting down people at e.g. a Sikh Temple.

One way the fundamentalist vigilantes can hope to combat their marginalization and political irrelevance in the wake of the Arab Spring is to manufacture a controversy that forces people to side with them. I suspect that is what they were doing in Egypt and Libya, in front of the US embassy in Cairo and at the rump consulate in Benghazi.

That the jihadis could not get bigger crowds up for their demonstrations suggests that they are seen as crackpots by their neighbours. In Libya, their actions may be a catalyst to the new prime minister, to spearhead a concerted effort to build new police and army forces on a faster timetable than had the transitional national council. Secular and nationalist Libyans have already announced a peaceful demonstration against the violence at Martyrs’ Square in Benghazi for Wednesday afternoon. I doubt the incidents will have long-term political significance. The Neocons will say they are symptoms of the so-called ‘Islamic winter’ after the Arab Spring, but that is just a way of making sure Western youth don’t identify (as they did during Tahrir) with Arab youth, marking them as a fundamentalist and threatening Other. There isn’t any ‘Islamic winter’ in Libya, and the Muslim Brotherhood in Egypt just barely squeaked by to win the presidency against a secular candidate– hardly a landslide.

The pretext for the demonstrations attacks was a YouTube film by Muslim-hater Sam Bacile, an Israeli-American ‘produced’ by provocateur Rev. Terry Jones, he of the Qur’an-burning fame. Things were made worse that two expatriate Coptic Christians are said to have been involved in the film. About ten percent of Egyptians are Christians, and the Muslim militants sometimes attack them. The Israeli right wing and its American supporters have a vested interest in driving a wedge between Americans and the Muslim world, since good Muslims on the whole stand against the Israeli colonisation of the Palestinian West Bank, the major project of the Israeli right wing. Good relations between the Muslim world and the United States might sway the latter to withdraw support for Israeli expansionism and aggression.

Misperceptions

Although some of the Egyptian demonstrators may have, as Ashraf Khalil argues, sincerely thought that the films demeaning the Prophet Muhammadwere being widely shown in American theatres and on television, I think the jihadis’ leadership cynically manufactured this ‘crisis’ in order to grab headlines and force the post-revolutionary governments to take a stand. If they stood with the Americans, they’d be guilty of blasphemy themselves. If they stood with the jihadis, they’d have surrendered some legitimacy to the latter. There is a third possibility, which is to deploy police or army against the vigilantes on grounds they had disturbed the peace, and simply declaring that the US embassy isn’t responsible for all the nonsense put up on YouTube.

In Egypt, the small crowd of 1500 just gathered outside the embassy walls (the Cairo embassy is a kind of fortress in the tony Garden City district). At one point they tore down an American flag flying outside the embassy grounds and ran up the black flag favoured by militants. (Those black flags are freely sold in Tahrir Square and elsewhere, and aren’t necessarily al-Qaeda flags. They just denote militancy and a desire for a fundamentalist government). Al-Masry al-Yawm has photos.

In Benghazi, the crowd of militants that gathered at the consulate may have turned violent in response to police or army intervention. The consulate was just a building in which the US set up during the Libyan Revolution, when Benghazi was the rebel capital, and which they kept going as a consulate after they reopened the US embassy in Tripoli. I met with a consulate official in early June there, and she wasn’t even sure the US would keep the consulate open. The small crowd in Benghazi turned violent, and at least one of its members had a rocket propelled grenade launcher, which he either loosed against the police and missed, hitting the consulate, or which he targeted the consulate with deliberately. (Hard to know which). The consulate caught fire and burned to the ground, and in the chaotic violence it is said that one US embassy staffer was killed.

Libya had parliamentary elections in July, in which the Muslim fundamentalists did poorly, with nationalists winning out. Some 20 percent of those elected were women. A couple of neighbourhoods in Benghazi are known for their strident fundamentalism, and jihadis did not allow a couple of polling stations in the city to open (though the vast majority of the city voted).

There is a small militant cell in Benghazi that has some RPGs and grenades. They have attacked the Red Cross offices, a convoy of the British consulate, and set off a pipe bomb in front of the US consulate last month. Most people in Benghazi are appalled by these extremists. The collapse of the authoritarian government of Muammar Qaddafi has left Libya without much in the way of professional police and army, both of which have to be rebuilt as institutions functioning in a democratic republic rather than as narrow instruments of oppression, control and torture.

Atypical of the new Libya

What happened in Benghazi was the action of a tiny fringe, sort of like Ku Klux Klan violence in the US. It isn’t typical of the new Libya, and Benghazi is not a lawless or militia-ridden city. One of the narratives of what happened there, in fact, is that the police may have been *too* heavy-handed in an attempt to curb the militants’ demonstration, provoking the latter to bring out their one RPG launcher.

The crowds both in Egypt and Libya were tiny. Their militancy is not typical of Egypt or Libya today, both of which are struggling toward more democratic forms of governance. In Cairo, there may have been a failure of policing; police in Egypt feel unfairly demonised because they had been seen as bulwarks of the Mubarak regime, and they often decline to show up to their jobs as a result of this low morale. This police foot-dragging has allowed an increase in petty crime, though Cairo is still far safer than most Western cities.

The government of Egypt is still pretty powerful, and will likely act to curb the militants, as it did in the Sinai recently. A merely fundamentalist president, Muhammad Morsi, probably cannot allow this challenge from the militants to pass. Moreover, this kind of thing is bad for tourism, a major part of the Egyptian economy, which had just begun improving this year after the turmoil of 2011.

On the other hand, there could be more trouble. The Egyptian Actors Guild announced an emergency meeting to study how to respond to the film smearing the Prophet. It may be that this obscure YouTube video could be taken unduly seriously even by the Egyptian mainstream.

Juan Cole is the Richard P. Mitchell Professor of History and the director of the Centre for South Asian Studies at the University of Michigan. His latest book, Engaging the Muslim World, is just out in a revised paperback edition from Palgrave Macmillan. He runs the Informed Comment website, where this article first appeared.