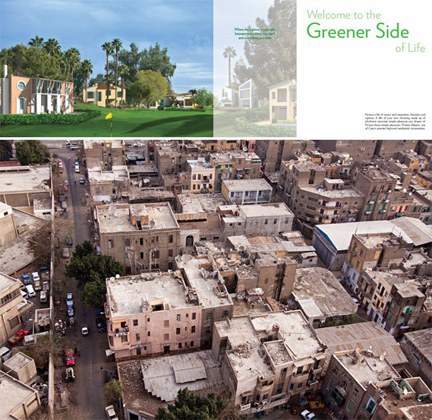

Top: Promotional image for Allegria, a gated community in Sheikh Zayed City, a suburb of Cairo, Egypt. [Image by SODIC] Bottom: Neighborhood in Cairo. [Photo by Brandon Atkinson]

by Karen Piper, The Design Observer Group, July 12, 2012

“Welcome to the Greener Side of Life” beckoned the billboard on Cairo’s Ring Road, which showed a man in a jaunty hat teeing off on a verdant golf course flowing into the horizon. I was stuck in traffic, breathing that mix of Saharan dust and pollution also known as “air,†so I could see the appeal. Somewhere outside the city, in a gated community called Allegria — Italian for “cheerfulness†— a greener life awaited. “Over 80% of Allegria’s land is dedicated to green and public spaces,” boasts the developer’s brochure, “meaning you’ll never lose the peace and tranquility which goes hand in hand with outdoor living.â€

It was a scorching hot summer, several months before the Egyptian revolution. Beneath the expressway sprawled the informal settlements where an estimated 60 percent of metropolitan Cairo’s 18 million residents live. [1] Some were using billboard poles to keep the brick structures from collapsing. Many did not have running water, and those who did found the taps drying up as water was diverted to the lavishly landscaped suburban developments with names like Allegria, Dreamland, Beverly Hills, Swan Lake, Utopia — a diversion that was straining the capacity of state-run water distribution networks and waste treatment plants. [2]

When Tahrir Square erupted in the winter of 2011, the international news media proclaimed a “social media revolution†spurred by pro-democracy Egyptians seeking to overthrow the repressive regime of President Hosni Mubarak. [3] To a large extent unreported was the fact that the country was also in a water crisis, having dropped below the globally recognized “water poverty†line of 1,000 cubic meters per person per year, down to 700 cubic meters per person. [4] It is no exaggeration to say that the January 25 Revolution was not just a revolution of the disenfranchised; it was also what some have called a “Revolution of the Thirsty.†[5] In a land almost without rain, the Nile River supplies 97 percent of renewable water resources, and these days an increasing share of that water is being directed to the posh suburban compounds — where many of Egypt’s political elite lives — to support that “greener side of life.” Meanwhile, in the years before the revolution, the state water utilities had dramatically hiked rates for residents in downtown Cairo, where some 40 percent of the population lives on less than $2 a day. [6]

For the rest of this article, click here.