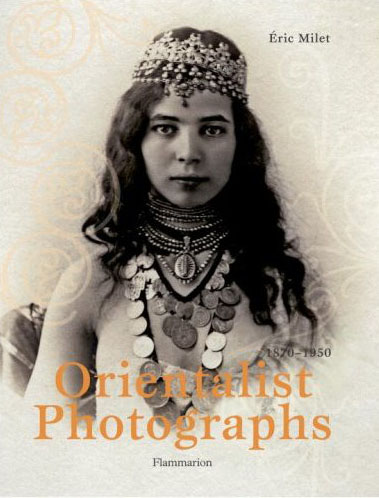

Cover of Milet’s book

In the Islamic Arts Museum in Qatar last December I bought a copy of a fascinating book of Orientalist Photographs by Éric Milet, who has worked as a tourist guide in Morocco for a number of years. The photographs, from both the 19th and 20th centuries, are accompanied by short vignettes. As Milet notes, “The ‘Oriental’ Maghreb was born in the darkrooms of Western photographers. A land of contrasts, revealed to the public at large by men and women who were delighted to have crossed to the ‘other side’ in their own lifetimes, constantly evoking the delights of this earthly paradise.” The book is well worth owning, not only to decorate your coffee table, but for easy, entertaining and informative reading.

As the author Malek Alloula has written, in his The Colonial Harem (1988), the ‘Oriental’ created by the photographer became “the oriental’ for the general public. The photographic lens is portrayed by Alloula as the structural enemy of the veil; capturing the image thus sought the removal of the veil and exposure of the female body as a voyeuristic object. Of course, the photographers who paid prostitutes to pose as “typical scenes” in the Maghreb were not the prudish Orientalist scholars, who would often render sexual argot in pseudo-scientific Latin (perhaps assuming that Victorian ladies did not know their Latin or at least that kind of vulgar Latin). But in the case of Milet’s book, the cover is a modern-day coverup that allows it to be sold in the likes of a bookstore of an Islamic Museum. The picture chosen for the cover has been altered so that the bare breast exposed by the photographer in this exquisite 1910 image (shown below) is lost in an arabesque and nipple-less swirl.

“Young Woman in Arab Costume, Algeria, 1910

The objectification of the female body, as shown by Alloula and many others, reinforced the image of the exotic and erotic harem girl open to the gaze of the European voyeur. True enough, although photographers of the time would expose the female body no matter what the nationality. Artistic nudes graced the major museums and were admired; the emerging visual realm of photographs quickly elided the erotic into the pornographic. But in the case of Milet’s book, undoubtedly due to the publisher rather than the author, there is a reversal, a kind of commercially smart prudery that removes the apparently offending body part, even though in so doing the very exposure for which such Orientalist photographs are critiqued is erased. It is not unlike sanitizing the Arabian Nights as children’s fairy tales.

In this case I am not suggesting we judge a book by its cover, but that we allow ourselves to be seduced into opening the book to see the range of images, some clearly bordering on the exploitative and others evincing a sensitivity usually reserved for poets.

Daniel Martin Varisco