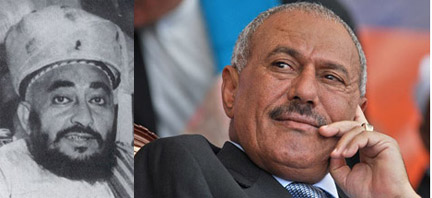

Imam Ahmad, left; Ali Abdullah Salih, right

[Webshaykh’s Note: This is a nice summary of the situation in Yemen just before Salih was wounded and left for Saudi Arabia.]

An avoidable civil war in Yemen that has already begun

by Brian O’Neill, The National, June 5, 2011

The scenes coming to us out of Yemen appear as raw and bloody chaos: running gun-battles through the streets, protesters screaming fiercely and the president, Ali Abdullah Saleh, apparently wounded in a mortar attack at the weekend (and rumoured to be headed to Saudi Arabia for treatment).

But while it looks like madness, the falling apart of Yemen is deeply rooted in the inexorable logic of its own history, the personalities of the major players and a looming generational shift. While civil war is not inevitable, circumstances have made it likely, and it may be too late to prevent the country from violently tearing apart its own seams.

Probably the biggest question swirling around the fighting is why? Not why is President Saleh clinging to power, but why has he established a series of feints and dodges that would appear to propel unrest rather than restore stability?

For instance, why did the president offer to sign a GCC-sponsored transfer of power, only to back away multiple times? If he had no intention of signing, why even bother with the pretence?

The answer to these questions is one of the keys to understanding why Yemen is where it is.

Mr Saleh has ruled parts or all of Yemen for over 30 years. But even the “all” in that sentence is misleading. Mr Saleh has never ruled all of Yemen, even if he has arguably the longest reach in his country’s ancient history. Yemen is governed by negotiation and appeasement, by the carrot and the stick, by squeezing one party while massaging the other.

Rule in Yemen is very personal; the president, like the Imam before him, is intimately involved in tribal politics – a game of swirling alliances.

But keeping competing power centres straight is far from the only problem. Yemen, as is now well-known, faces essentially every economic and social problem a country can face, from running out of water to a massive youth explosion with no jobs forthcoming. Throw in the political problems, and you can see how running the country is a constant game of spinning plates. Spin one and rush off to spin the other, never having time to balance anything.

Mr Saleh has been a master of this, constantly applying bandages without tending to the suppurating wounds underneath. In a way, this is understandable; there are enormous problems to deal with. But thinking in the long-term takes your eyes off immediate survival (Mr Saleh’s two immediate predecessors were murdered). But it has caught up, and all the issues have come to a head.

Mr Saleh still thinks he can buy himself more time. He thinks if he offers to sign any GCC deal to step aside, it will give him some breathing room which he can use to game the system yet again. Yet he doesn’t seem to realise that the ecstasies and agonies of the Arab Spring have caused the game to change.

There may be something deeper in Mr Saleh’s calculation. For a time it appeared he believed he was the only one who could keep Yemen together, that he was the nation. And in a way he was right, though it is clear that he is now a singular source of instability.

Perhaps part of him was actually looking forward to stepping down, on his own terms. It is a very hard thing to realise that you are going to be remembered as the tyrant.

Mr Saleh’s madness now – shooting protesters, and by some accounts allowing al Qa’eda in the Arabian Peninsula to take over a town – is just another way to buy himself time. Yet this time, Mr Saleh may not be able to control the demons he has unleashed.

Mr Saleh’s biggest foes are the al Ahmar brothers, leaders of the Hashed tribal federation, Yemen’s largest. (It’s important to recognise that this is a federation, not a single tribe. The president’s tribe is also in the Hashed federation, so there are civil wars within civil wars). The brothers are the sons of Abdullah al Ahmar, who until his death in 2007 was the second-most powerful figure in Yemen.

The elder al Ahmar was older than Mr Saleh, but they were both part of what could be called Yemen’s heroic epoch, those who overthrew the Imam and forged a republic.

For years there has been speculation about the next generation, particularly the rivalry between Mr Saleh’s family and the al Ahmar boys. Sadeq al Ahmar is the leader of the Hashed, but Hamid al Ahmar is a link between tribal and business leaders, and is Mr Saleh’s top critic.

The rivalry that has been playing behind the scenes has now exploded onto the streets. The al Ahmars sensed that Mr Saleh has been weakened fatally by the protests, and either fired first or goaded Mr Saleh into firing. War is propaganda; the truth doesn’t matter.

The al Ahmar boys also wanted to step in to take the initiative away from any other potential rivals. Hamid al Ahmar has suggested he’d want the presidency to go to a southerner, in the name of inclusion, but even if he is sincere there is little doubt where the power would lie.

Against this backdrop many are asking whether civil war is inevitable. Yet it seems to have already started. The media might use the terms “civil war” and “tribal war” interchangeably. In this case, they will be correct to do so, stumbling backwards into wisdom. Both sides are rallying support from family and tribes.

It isn’t too late to pull back from the brink, if the parties agree that a chilly peace is less disastrous than an outright war. The Yemeni tradition of dealing with your enemy provides far more leverage than any outside power can. But if weakness is sensed, this could quickly escalate and spiral into the war we’ve feared for years.

Brian O’Neill is a former writer and editor for the Yemen Observer. He is currently an independent analyst in Chicago