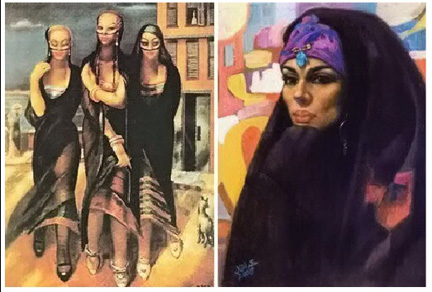

Mahmud Saʻid,The Girls of Bahari; and an untitled portrait by Abdelal Hassan (2000; current location unknown)

[Note: The following is an excerpt from a fascinating discussion of Orientalist art by the philosopher, cultural critic and poet Pino Blasone, whose knowledge of both European and Arab cultures brings a fresh lens to the discussion of the genre. The article is entitled “Orientalism: Veiled and Unveiled†and is available in its entirety online.]

In an online weekly supplement to the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram (17-23 May 2007, Issue No. 845), we can read an interesting article by Mohammed Salmawy, entitled“Dialogues of Naguib Mahfouz: A passion for the Artsâ€. Notoriously Naguib Mahfouz, or Nagib Mahfuz, is the best Egyptian novelist of the 20th century, died in 2006 and received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1988. Salmawy reports and comments a late interview to him. In particular, let us consider a passage from that: “My first exposure to the plastic arts was in the late 1920s… I remember reading an article by Al-Ê»Aqqad about an artist called Mahmud SaÊ»id. This was kind of unusual, for art wasnʼt really big back then. So for someone like Al-Ê»Aqqad to write a whole article about an artist was a bit of a shock. After that, I learned that SaÊ»id came from a prominent family and had a brilliant career in the judiciary, a career that he abandoned to dedicate his life to art. From then on I made a point of going to all SaÊ»idʼs exhibitions. […] Some of SaÊ»idʼs paintings are still imprinted on my mind: The Girls of Bahari, The Liquorice Merchant, and those splendid portraits of countryside womenâ€.

Mahfuz goes on by emphasizing some artistic influences – especially of SaÊ»idʼs paintings – on his own literary production. Here let us focus upon The Girls of Bahari, since not seldom this Surrealistic fashioned masterpiece, executed in 1935 or 1937, has been considered a true beginning of contemporary painting in Egypt by local art-historians. In reality, we have two versions of it, one of which – today in the Mahmud SaÊ»id Museum at Alexandria – is larger and includes more characters. In both versions the central represented subjects are three charming women walking together, full length and frontally portrayed. A long transparent veil, the so called melayah laf often used in the belly dance, half covers their faces. In the background, we can see the Corniche of Alexandria, so that the beautiful and elegant – just a bit equivocal, indeed – ladies may resemble veiled sirens proceeding from the sea. Actually, Bahari is the name of a popular seaside part of the town. Yet Bahari is also an adjective generically employed to design the Lower Egypt dwellers, close to the Mediterranean sea (in Arabic, bahr means “seaâ€). With a poetic play on words, the original title of the painting BanÄt BahÄri might sound like BanÄt al-Bahri, “Daughters of the Seaâ€.

Like Osman Hamdi in Turkey, Mohammed Racim in Algeria or Abdul Qadir al Rassam in Iraq, albeit in different ways, Mahmud SaÊ»id can be counted among a few pioneers of a figurative art in the Islamic World. He studied after Italian painters in Egypt and French ones in Paris. His emancipation from the Orientalism was well expressed in his declared persuasion that, generally in the field of a contemporary culture, “the question is not just emerging and disappearing of trends, rather it is the issue of domestic trends in every countryâ€. However, in his case like in others the same old problem was the irruption of a figural representation into a non representative and an iconic civilization, like that of the Near and Middle East. Also for him, willingly such a problem coincided with the question of female veiling and unveiling. In itself, easily the pictorial representation involves such a question. In BanÄt BahÄri, once again the problem is resolved with the expedient of a transparent veil. Nay, there, this veiled transparency is the implied subject of the picture. At the same time, The Girls of Bahari look like the latest sisters of the veiled Hellenistic statuettes of Tanagra, admired by the artist in a wide Mediterranean retrospective view.

Even more than reflecting a foreign novelty, SaÊ»idʼs art strives to portray his own reality and to recover a local, nearly forgotten figural tradition. In other female portrayals by him, indeed his unveiling goes so far, that his are some of the finest nudes in the Egyptian and Arabian modern painting. Yet here we like to pay better attention to “those splendid portraits of countryside womenâ€, mentioned by Nagib Mahfuz, such as Naima (1925;Shafeiʼs collection, Cairo) or Girl with Red Headscarf (1947; sold at Christieʼs, Dubai, in 2007). Their faces are unveiled, but a coloured scarf and a dark veil cover the head of both of them, according to a popular usage. Rather than “Daughters of the Sea†these appear to be daughters of the country, as also attested by the landscape in the background, peculiarly in the former portrait rendering the life of an Egyptian village. The conversion from Orientalism to a national figurative painting is now complete. And the female figure has played a decisive role on this path, might it be in a realistic or surreal autonomous manner.

Even if Mahmud SaÊ»id was not the sole Egyptian “pioneerâ€, his lesson influenced later painters, in the local contemporary art scene. Here we can just mention Abdelal Hassan Ghouniem, born at Port SaÊ»id in 1944. In his portrayals of countryside or popular women,scarves and veils maintain a deal of the seductiveness perceptible in certain works of SaÊ»id.Furthermore, their typical beauty and make-up may recall the ancient Egyptian, carved or painted, portraits, like those discovered by the archaeologists in the oasis of Al-FayiÅ«m. In the today Arabic area, Egypt is that country, where a so strong plastic or figurative tradition– and related imagery – preceded any religious forbidding of images, that the artworks of the past are always susceptible to return to exert an ascendancy over visual arts, besides or apart from Orientalistic interferences. Then, the Sea and the Country might sound like symbolic concepts of different dimensions and horizons, between which not only a modern Eastern art but also specific national identities could find their cultural ways of realization.