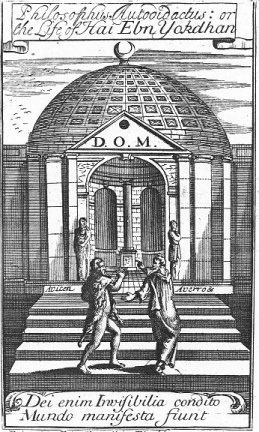

While teaching Hofstra’s Honors College Culture and Expression course this term, I suggested the text Hayy ibn Yaqzan by the Andalusian Muslim scholar Ibn Tufayl, who died in 1185 CE, as an antidote to the otherwise “Great Western” bent such courses inevitably take. Ibn Tufayl’s 12th century text is a brilliant fable built on the author’s knowledge of earlier philosophical arguments by Greek (including Plato and Aristotle) Neoplatonist and Muslim (such as Al-Farabi and Ibn Sina) intellectuals and also on the best science of his day. The plot revolves around a child stranded or spontaneously generated (take your pick) on an island, brought up by a nurturing doe and then growing through basic logic from an empirical youth to an enlightened mystic. In effect the hero, Hayy ibn Yaqzan, comes to the ultimate state of being a Muslim without ever having heard of Muhammad or being introduced to Islamic rituals and law. Ibn Tufayl turns St. Augustine’s “original sin” on its head, although still arriving at belief in one God as a First Cause, Prime Mover or Prime Sustainer.

The book is worth a read, since so many European intellectuals did in fact read it after it was translated into English by Simon Ockley in 1708. If you have ever read Robinson Crusoe or Tarzan, this book is worth checking out for its literary prehistoric value. Ibn Tufayl presents a strikingly modern view on the role of symbolism, no matter what you think of his ultimate theological spin. Here is an example from late in the book, once Hayy has gone as far as reason will take him:

Having attained this total absorption, this complete annihilation, this veritable union, he saw that the highest sphere, beyond which there is no body, had an essence free from matter, which was not the essence of that one, true one, nor the sphere itself, nor yet anything different from them both; but was like the image of the Sun which appears in a well polished looking-glass, which is neither the Sun nor the looking-glass, and yet not distinct from them. And he saw in the essence of that sphere, such perfection, splendour and beauty, as is too great to be expressed by any tongue, and too subtle to be clothed in words; and he perceived that it was in the utmost perfection of delight and joy, exultation and gladness, by reason of its beholding the essence of that true one, whose glory be exalted.

He saw also that the next sphere to it, which is that of the fixed stars, had an immaterial essence, which was not the essence of that true one, nor the essence of that highest sphere, nor the sphere itself, and yet not different from these; but is like the image of the Sun which is reflected upon a looking-glass from another glass placed opposite to the Sun; and he observed in this essence also the like splendour, beauty, and felicity, which he had observed in the essence of the other highest sphere. He saw likewise that the next sphere, which is the sphere of Saturn, had an immaterial essence, which was none of those essences he had seen before, nor yet different from them; but was like the image of the Sun, which appears in a glass, upon which it is reflected from a glass which received that reflection from another glass placed opposite to the Sun. And he saw in this essence too, the same splendour and delight which he had observed in the former. And so in all the spheres he observed distinct, immaterial essences, every one of which was not any of those which went before it, nor yet different from them; but was like the image of the Sun reflected from one glass to another, according to the order of the spheres. And he saw in every one of these essences, such beauty, splendour, felicity and joy, as eye hath not seen nor ear heard, nor hath it entered into the heart of man to conceive; and so downwards, till he came to the lower world, subject to generation and corruption, which comprehends all that which is contained within the sphere of the Moon.

This World he perceived had an immaterial essence, as well as the rest; not the same with any of those which he had seen before, nor different from them; and that this essence had seventy thousand faces, and every face seventy thousand mouths, and every mouth seventy thousand tongues, with which it praised, sanctified and glorified incessantly the essence of that one, true being. And he saw that this essence (which seemed to be many, though it was not) had the same perfection and felicity, which he had seen in the others; and that this essence was like the image of the Sun, which appears in fluctuating water, which has that image reflected upon it from the last and lowermost of those glasses, to which the reflection came, according to the forementioned order, from the first glass which was set opposite to the Sun. Then he perceived that he himself had a separate essence, which one might call a part of that essence which had seventy thousand faces, if that essence had been capable of division; and if that essence had not been created in time, one might say it was the very same; and had it not been joined to its body so soon as it was created, we should have thought that it had not been created. And in this order he saw essences like his own, which had belonged to bodies existing heretofore but since dissolved, and essences belonging to bodies which existed together with himself; and that they were so many as could not be numbered, if we might call them many; or that they were all one, if we might call them one. And he perceived both in his own essence, and in those other essences which were in the same order with him, infinite beauty, splendour and felicity, such as neither eye hath seen, nor ear heard, nor hath it entered into the heart of man; and which none can describe nor understand, but those which have attained to it, and experimentally know it.

Then he saw a great many other immaterial essences, which resembled rusty looking glasses, covered over with filth, and besides, turned their backs upon, and had their faces averted from those polished looking-glasses that had the image of the Sun imprinted upon them; and he saw that these essences had so much filthiness adhering to them, and such manifold defects as he could not have conceived. And he saw that they were afflicted with infinite pains, which caused incessant sighs and groans, and that they were compassed about with torments, as those who lie in a bed are with curtains; and that they were scorched with the fiery veil of separation, and sawn asunder by the saws of repulsion and attraction. And besides these essences which suffered torment, he beheld others there which appeared and straightway vanished, which: took form and soon dissolved. And he stayed a while regarding them intently, and he beheld an immensity of fear and vastness of operation, an incessant creation and ordaining wisdom, construction, and inspiration, production and dissolution. But after a very little while his senses returned to him again, and he came to himself out of this state, as out of a swoon; and his foot sliding out of this place, he came within sight of this sensible world, and lost the sight of the divine world, for there is no joining them both together in the same state. For this world in which we live, and that other are like two wives belonging to the same husband; if you please one, you displease the other.

Now, if you should object, that it appears from what I have said concerning this vision that these separated essences, if they chance to be united to bodies of perpetual duration, a the heavenly bodies are, shall also remain perpetually, but if they be united to a body which is liable to corruption (such an one as belongs to us reasonable creatures) that then they must perish too, and vanish away, as appears from the similitude of the looking-glasses which I have used to explain it; because the Image there has no duration of itself, but what depends upon the duration of the looking-glass; and if you break the glass, the image is most certainly destroyed and vanishes. In answer to this I must tell you that you have soon forgot the bargain I made with you. For did not I tell you before that it was a narrow field, and that we had but little room for explication; and that words however used, would occasion men to think otherwise of the thing than really it was? Now that which has made you imagine this, is, because you thought that the similitude must answer the thing represented in every respect. But that will not hold in any common discourse; how much less in this, where the Sun and its light, and its image, and the representation of it, and the glasses, and the forms which appear in them, are all of them things which are inseparable from body, and which cannot subsist but by it and in it, and therefore depend upon Body, and perish together with it.

§ 96

But as for the divine wssences and sovereign spirits, they are all free from body and all its adherents, and removed from them at the utmost distance, nor have they any connection or dependence upon them. And the existing or not existing of body is all one to them, for their sole connection and dependence is upon the essence of that one true necessary self-existent being, who is the first of them, and the beginning of them, and the cause of their existence, and he perpetuates them and continues them for ever; nor do they want the bodies, but the bodies want them; for if they should perish, the bodies would perish, because these essences are the principles of these bodies. In like manner, if a privation of the essence of that one true being could be supposed (far be it from him, for there is no God but him (12)) all these essences would be removed together with him, and the Bodies too, and all the sensible World, because all these have a mutual Connection.Now, though the sensible world follows the divine world, as a shadow does the body, and the divine world stands in no need of it, but is free from it and independent of it, yet notwithstanding this, it is absurd to suppose a possibility of its being annihilated, because it follows the divine world: but the corruption of this world consists in its being changed, not annihilated. It is this that the glorious book expresses where it speaks of moving the mountains and making them like tufts of wool, and men like moths, and darkening the Sun and Moon; and eruption of the sea, in that day when the Earth, shall be changed into another Earth, and the Heavens likewise. (13) And this is the sum of what I can hint to you at present, concerning what Hayy Ibn Yaqzân saw, when in that glorious state. Don’t expect that I should explain it any farther with words, for that is even impossible.