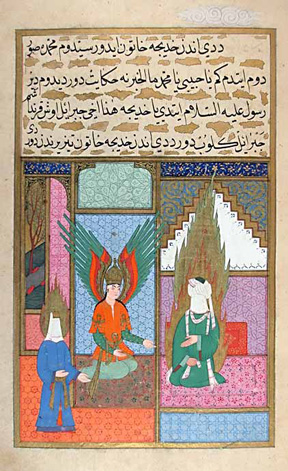

Prophet Muhammad with the Angel Gabriel. Miniature from the Ottoman Empire, c. 1595 CE (Topkapi Museum, Istanbul)

Why Islam does (not) ban images of the Prophet

By Omid Safi, Newsweek, May 2, 2010

When a pair of adolescent and anonymous Muslim bloggers (“Muslim Revolution”) threatened the producers of South Park for depicting the Prophet Muhammad in a bear suit in an April 2010 episode, pundits responded by saying that the “Muslim Revolution” folks were extremist idiots (true) and that they were offended because Islam bans the depiction of the Prophet Muhammad (not true).

When the Danish cartoon controversies broke out in 2005, many pundits–and some Muslims–stated that Muslims were offended because Muslims have never physically depicted the Prophet.

That is actually not the case, and marks yet another example of what is at worst an acute sense of religious amnesia, and at best a distortion of the actual history of Islamic practices: Over the last thousand years, Muslims in India, Afghanistan, Iran, Central Asia and Turkey did have a rich courtly tradition of depicting the various prophets, including Prophet Muhammad, in miniatures.

These miniatures were patronized by pious Muslim rulers, and were often richly illustrated with verses from the Qur’an, and the biography of the Prophet’s life. Yet very few Muslims today, and even fewer non-Muslims, are aware of this rich heritage. In my new biography of the Prophet Muhammad, titled Memories of Muhammad, I have established the rich Muslim heritage of producing pietistic images of the Prophet, not in the South Park and Danish Cartoon fashion, but as devout works of art to help Muslims remember the Prophet of God, and in turn, God.

It is true that Muslims do not produce graven images to be displayed in places of worship, such as mosques. In place of pictorial representations, there is a rich tradition of calligraphy, and ornate arabesque patterns, and natural designs. Yet outside of the mosque space, and in particular in the courtly context, Muslims have historically embraced the production of miniatures depicting these sacred narratives, which was always a treasured courtly art. In the modern age, with the availability of the printing press, many of these images are now available as posters and postcards, and coffee-table books, in different parts of the Muslim majority context.

The most iconic images of the Prophet deal with the Prophet’s journey from the Ka’ba in Mecca to the al-Aqsa mosque in Jerusalem. This scene became one of the favorites of Muslim artists, who often depicted Muhammad riding what can only be described as an angel-horse (buraq). Some of the extraordinary miniatures even depict Muhammad’s face. More widespread are the versions in which his face and whole visage are engulfed in a halo of light and flame. Here is an example (from the British Library) of one of the classic images of the Prophet Muhammad’s Heavenly Ascension (Mi’raj):

Nezami

Muhammad ascending through the heavens, accompanied by angels. From Nezamis Khamsa, produced in Tabriz, Iran. The British Library Board

The production of the images of the Prophet was not a Sunni/Shi’i divide. Historically, the bulk of the images were produced by Sunni artists, though today one finds them more common in Shi’i Iran and Sunni Turkey. For reasons that are hard to explain, in the Arab context there was never a rich tradition of produced pictorial representations of the Prophet. Instead, the creative energy of Muslims in that context was channeled toward a rich poetic tradition in praise of the Prophet.

My familiarity with the intensity of Muslim debates about whether or not the Prophet should be depicted is not theoretical, but deeply personal. My family’s narrative is very much a part of the great age of globalization, this age of moving back and forth across the planet. I was born in the United States, but raised as a child in Iran during the 1970s and the first half of the 1980s. In 1985, we had to leave Iran, and had to do so quickly. I still remember the six of us packing what we could into two suitcases. Most of what we packed were the expected clothing items. The one exception was a beautiful image, an icon of sorts, of the Prophet Muhammad that had always adorned our home in Tehran. It had graced the dining room in our home, and it seemed unthinkable to me to either leave it behind or move into a new home where meals would not be presided over by the image of Muhammad. So I carefully tucked the image away, and I have carried it with me to each home I have lived in over the last few decades.

This image is a lovely depiction of a kind, gentle, yet resolute Prophet, holding on to the Qur’an and looking straight at the viewer with deep and penetrating eyes. He is depicted as a handsome man, with deep Persian eyes and eyebrows, and wearing a green turban. We all imagine the great ones at least partially in our own image; in the case of this Iranian icon, Muhammad is depicted not as an Arab but with distinctly Persian features. Then again, that is probably not any stranger than imaging a first-century Palestinian Jew (Jesus Christ) with the European features of blond hair, white skin and blue eyes!

Since our return to the United States, the icon has once again been displayed in our house. Our home also features images of Christ and the Buddha, but having an icon through which to imagine the presence of the Prophet has been important for me and my family.

Whenever Iranians and Turks came to our home, they would recognize the image as a common one they had seen on posters in Iran. But something strange would happen when we invited to our home Sunni Muslim friends from Pakistan, Afghanistan, or Egypt, who experienced a cognitive dissonance of sorts: how could a pious Muslim not only make an image of the Prophet but also display it proudly in his home? Once a dear friend from Pakistan came to our home for dinner, and we shared a wonderful meal. A great lover of Islamic arts, he admired the many examples of Islamic calligraphy around our home, and we had a lovely time deciphering the Arabic inscriptions. He finally came to pause in front of the image of the Prophet and politely asked who the image was depicting. I was surprised that this learned friend, very knowledgeable about Islam, would not have immediately identified the very common image of Muhammad; I stated that, of course, it was the Prophet. My friend’s complexion changed from disbelief to offense, and he proceeded to emphatically state that it could not be, because “Muslims do not depict the Prophet.” His insistence was partially out of concern that, in our devotion and love toward the Prophet, Muslims not fall into the trap of worshiping Muhammad instead of the God of Muhammad.

I did my best to inform him that there were millions of such depictions in Iran and elsewhere, and that for many of us it was not a distraction from God but rather a reminder of God to focus on the Messenger of God. And yet I remained unsure of how to respond to his assertion that “Muslims do not depict the Prophet.” Wasn’t the very item that he was standing in front of proof that at least some do? Faith is sometimes a very delicate matter that is best handled with care and sensitivity. Now when Muslim friends come over to our home and ask about the image, I try to surmise from what I know about them whether I should reveal the identity or simply state: “It is an image of a holy man who is exceedingly dear to me.”

I bring up this example to indicate that different Muslims have always had differing memories of Muhammad. Over the years I have come to see that many of these memories are motivated by differing aesthetics and varying understandings, but that the memories of almost all Muslims are rooted in a devotion to Muhammad. My family’s display of the image remains part of our devotion, and the friend’s protest was also part of his devotion to make sure that the memory of the Prophet was not sullied by undue innovations.

In my recent biography of the Prophet, titled “Memories of Muhammad: Why The Prophet Matters,” I have taken care to produce about 20 of the pietistic and sacred images produced by Muslim artists over the centuries. These are as far from the Danish cartoon images as one can get: they are works of devotion, illuminated by faith, and imbued with a deep sense of love. There are other options available to Muslims than either accepting the Danish Cartoonist caricatures of the Prophet, or responding in pure anger and hatred. One such answer is a return to the rich pietistic Islamic tradition of depicting the Prophet who was sent, according to the Qur’an, as a mercy to all the Universe.

Omid Safi is Professor of Religious Studies, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and author of “Memories of Muhammad: Why The Prophet Matters”.