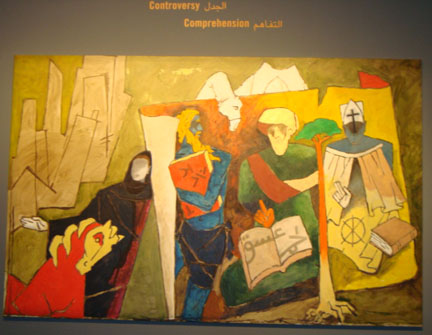

Hussain’s painting courtesy of Dr. Bruce Lawrence

One of the most famous, and at times infamous, painters in modern India is M.F. Hussain, who was born in 1915 and currently resides in London. He is perhaps best known for the controversy over his nude paintings, especially one that depicted “Mother India” and caused such a major backlash that he removed it from view. Less known, perhaps, are his paintings about Islam. Bruce Lawrence recently sent me several illustrations of paintings by Hussain on Islamic themes. Several of these were commissioned by Sheikha Mouza of Qatar for the Islamic museum in Doha. The picture above portrays the three monotheisms as “People of the Book.” As a painter it is clear that Mr. Hussain is less interested in promoting a particular religion than in celebrating the human spirit through his art.

Here is Bruce’s description of the painting above (this is an excerpt from a volume on Hussain, edited by Sumathi Ramaswamy and to be published by Routledge in October 2010):

This work is the inaugural canvas. It is an enormous acrylic painting that depicts a rabbi reminiscent of the Jesus figure in the Last Supper in Red Desert (LSRD) painting. In size it is even larger than LSRD and it appeared at the entrance to the gallery at the Doha Museum of Islamic Art opening in November 2008 with the title in English and Arabic Debate (al-jadal)/Comprehension(at-tafahum), it portrays three central figures, along with one anonymous bystander. It is not the first painting on the theme of trimurti or a triumvirate, since he had earlier done water color evocations of tree major Hindustani poets – Ghalib, Iqbal and Faiz. Debate/Comprehension, like that earlier timurti, projects a distinctly Muslim optic. First it points to the importance of the book. Unlike the book as an open, blank page object in the Untitled work from the Lost Continent Series of 2005, the book here is marked explicitly in the middle, elliptically in the far left, and canonically in the far right. According to Islamic tradition, there is a vast celestial scroll that encompasses all human destiny as also every divine mandate. Umm al-kitab is literally, the prototype or mother of all books; on its pages are writ the fate of all humans but also the content of every divine writ or scripture. As scripture, it is transmitted to human beings through prophecy, specific to each group, each language, and each time in the unfolding of history.

In the Abrahamic tradition those prophecies include the Torah, the Prophets, the Psalms, the Gospel and, of course, the final prophecy to humankind, the Qur’an. In MF Husain’s opening canvas for the Doha series, the three central figures each have a book marking who they are. The Bishop to the right has a closed book; one may suppose that is the Gospel, though it might include the Torah, Prophets, and Psalms as well. Its custodian, the Bishop, not only has a cloak and mitre but also a wheel symbolizing his secular authority.

The figure on the left can either be an anonymous rabbi or perhaps an anticipation of the Jesus figure in LSRD, and the book he holds, though marked in an indecipherable language, could allude to Hebrew. By contrast, the figure in the middle with a scarf and turban holds a book that is not only open but marked with five Arabic letters: Ha- mim -‘ain – sin – qaf. It is striking that three of these five – ha-mim-qaf represent the Arabic signature of Husain’s name, even though to be literally accurate, one would expect his name to be alphabetized as ha-mim-fa. The proximity of fa to qaf allows for the interchange, but even more importantly, it makes his Arabic signature itself a summary reference to ha-mim-‘ain-sin-qaf, which is the metonymic invocation of Qur’an 42. Titled al-Shura, or ‘consultation’, it is arguably his ‘favorite’ Quranic surah, since he quotes it twice in the three paintings that address the theme of Christian-Muslim dialogue in the Doha series.

The juxtaposition or conjuncture of opposites is also made clear in the hand gestures of the ‘Bishop’ and the ‘Imam’. The Bishop confirms with the thumb, forefinger and middle fingers of his right hand, ‘three’, for the Trinity, while the Imam holds up his index figure, also on the right hand, indicating one’ or oneness, tawhid, the central doctrine of Islamic belief. Similarly, the colors confirm the differences on a continuum of assent, represented by the folded back page, orange and yellow on the front indicating spiritual aspiration, with red and white on the back indicating passion and purity. Each of the three figures also projects what they embody through their colors: the Bishop in gray is austere and remote, the Imam in green is reflective, even philosophical, while the Rabbi in Nilotic blue symbolizes attachment to nature and primal elements, further accented by his minimal garb, a mere waistcloth, compared to the full body cloaks of the Imam and Bishop.

Hussain’s interfaith work is not without detractors, who often see his work as anti-Hindu. One angry website contrasts his paintings of naked Hindus with those of clothed Muslims, as noted below, in an ad hominem attack on him:

“Left: Full Clad Muslim King and naked Hindu Brahmin. The above painting clearly indicates Husain’s tendency to paint any Hindu as naked and thus his hatred. Right: Naked Bharatmata – Husain has shown naked woman with names of states written on different parts of her body. He has used Ashok Chakra, Tri-colour in the painting. By doing this he has violated law & hurt National Pride of Indians. Both these things should be of grave concern to every Indian irrespective of his religion.”