The hunting trip is a time when falconers night spend up to six weeks away from their homes, families and business in the desert. These days the trip need no longer be frugal and it is possible to provide every comfort.

So writes the Qatari veterinarian Faris al-Timimi in his 1987 book Falcons & Falconry in Qatar (Doha: Ali bin Ali Press). I met Dr. al-Timimi in 1988, when I was conducting research in Qatar on the seasonal almanac knowledge of the Gulf. He showed me some of his prized falcons and explained the long established practice of hunting with falcons in Qatar. At that time a superb falcon might be worth $30,000, so I can only imagine what a prize falcon would sell for in today’s commercially enhanced Qatar. Unlike many other sports, where the animals are domesticated and, in Darwinian terms, bred for the task, the best hunting birds are said to be those captured young in the wild. Those that are captured and kept for a future hunting season are those who excel at catching the bustard (Chlamydotis undulata), known in Arabic as the houbara.

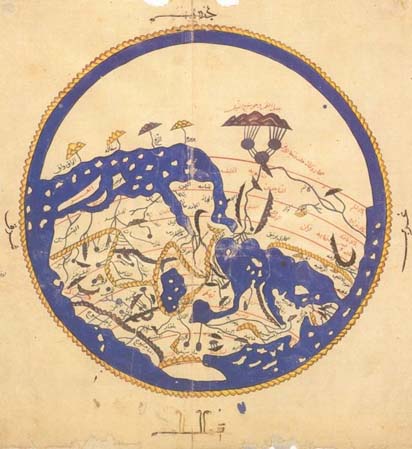

There is a rich literature on Arab falconry,known as bayzara in Arabic. In his 10th century bibliographic survey of Arabic books, Ibn al-Nadīm listed ten books on the subject, in addition to the numerous references that would have been found in other kinds of texts. Today both texts and videos are only a click away in cyberspace, including sites devoted specifically to falcon hunting in Qatar. Al-Jazeera recently posted a photographic montage on the most recent hunting expeditions in Qatar. In addition to the use of falcons, followed by high-speed cars rather than racing camels, there is the use of hunting dogs. While the trajectory of a falcon on its prey is purely natural, the sport of hunting dogs has reached a true dog-days syndrome, as an contraption-bound gazelle along a mechanical path substitutes for the open range, the host of SUVs spurting up dust. I do not doubt that Abbasid princes or Mamluk sultans would have adopted the same vehicular superiority, if they had known it, but there is something pitiful about an animal trapped in a mechanical game that does not give the prey a sporting chance.

For a set of extraordinary pictures by photographer Matthew Cassel on falcon hunting in Qatar al-Jazeera, click here.

Daniel Martin Varisco