Digging up the Saudi past: Some would rather not

by Donna Abu-nasr, AP, August 30th, 2009

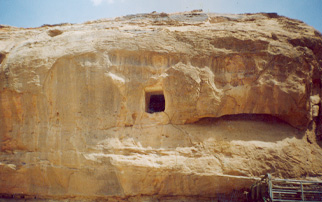

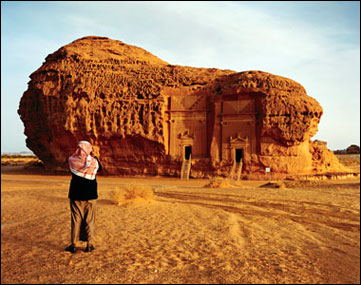

RIYADH, Saudi Arabia — Much of the world knows Petra, the ancient ruin in modern-day Jordan that is celebrated in poetry as “the rose-red city, ‘half as old as time,’†and which provided the climactic backdrop for “Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade.â€

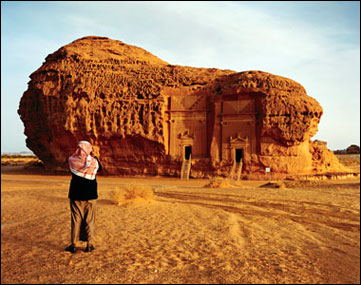

But far fewer know Madain Saleh, a similarly spectacular treasure built by the same civilization, the Nabateans.

That’s because it’s in Saudi Arabia, where conservatives are deeply hostile to pagan, Jewish and Christian sites that predate the founding of Islam in the 7th century.

But now, in a quiet but notable change of course, the kingdom has opened up an archaeology boom by allowing Saudi and foreign archaeologists to explore cities and trade routes long lost in the desert.

The sensitivities run deep. Archaeologists are cautioned not to talk about pre-Islamic finds outside scholarly literature. Few ancient treasures are on display, and no Christian or Jewish relics. A 4th or 5th century church in eastern Saudi Arabia has been fenced off ever since its accidental discovery 20 years ago and its exact whereabouts kept secret. Continue reading Saudiana Jones vs the “Days of Ignorance” →