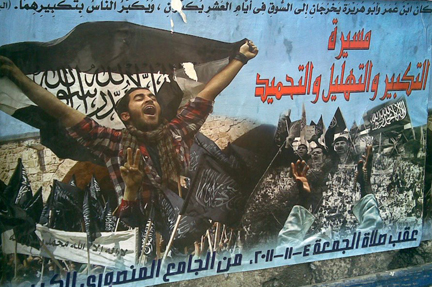

Poster in Tripoli, Lebanon; photography by Estella Carpi

Unearthing a misconceived “normalization†of violence in Beirut. The October car bomb in relation to generalized insecurity.

The 19th October 2012 car bomb in Beirut’s Ashrafiyye, within the Eastern district of the Lebanese capital, shed light on the re-articulation of the relations between the State, allegedly “inexistent†in the Lebanese context, and its society that lives in the constant effort to subjectively reformulate their citizenship, in the lack of a commonly shared nationhood.

New outbursts of violence seem to give a reason to the state to promote its technology of control, as Michel Foucault would put it. This complex re-articulation of relations has come to the fore with the October 26 White March from Martyrs Square (Beirut Downtown) to Sassine Square (Ashrafiyye, where the explosion was one week before). The “White Marchâ€, in which no political flag but the national Lebanese was waved, wanted to be considered as an act of social refusal of further violence and national solidarity, in addition to their political contestation of both the 14 and 8 March coalitions, which have politically and socially polarized the country into two sections after Hariri’s murder in February 2005. The White March mainly had the implicit aim of contesting the taken for granted watershed between what is “normal†and what is not in Lebanese parameters.

Social fear, as well as the perception of risk in Beirut, has specific historical explanations. Lebanese society seems to be doomed to live in a not-war-not-peace state, as Jeffrey Sluka used to define Northern Ireland during the clashes between Protestants and Catholics. Such an unstable state has engendered a social attitude towards violence that has been named by political scientists and journalists as “normalizationâ€, which, in light of the Lebanese reaction to the last explosion, begs for a re-conceptualization. Continue reading Being Normal and being Car Bombed →

“Their Imperial Majesties the Shah and Queen Farah greet distinguished guests from the United States: Vice President and Mrs. Lyndon Johnson and their daughter, who visited Iran last summer.

“Their Imperial Majesties the Shah and Queen Farah greet distinguished guests from the United States: Vice President and Mrs. Lyndon Johnson and their daughter, who visited Iran last summer.