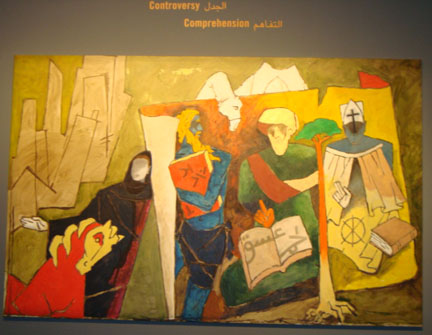

Fresco from the Church of the Nativity in Bethlehem

The Basilica of the Nativity in Bethlehem

In 1099 a detachment of Crusaders commanded by Tancredi took possession of Bethlehem. The night of Christmas 1100 Baldwin, brother of Godefroy de Bouillon, was crowned the first king of Jerusalem in the Basilica of the Nativity, the only early Christian church in Palestine still intact on the arrival of the Crusaders. Subsequently, the Crusaders, after having fortified the sanctuary together with the surrounding monasteries, added a bell tower to the front, restored the double side entry to the Grotto under the presbytery of the basilica and built the Augustinian convent with the cloisters to its north. Between 1165 and 1169 the walls were decorated with mosaics, thanks to the collaboration between King Amalric of Jerusalem and Emperor Manuel Comnenus of Constantinople. The authors of the project were Ephraim a monk, painter and mosaicist assisted by Deacon Basilius. From the descriptions of the pilgrims we are able to determine the entire mosaic decorative cycle. The Nativity decorated the apsidiole of the Grotto, the Tree of Jesse, father of King David and progenitor of Jesus, the inner wall of the facade. On the walls a procession of Angels facing toward the Grotto at the top was followed, at the centre, by texts in Greek and Latin of the Councils in designs of the cities in which they were held, and by busts of the Ancestors of Jesus at the bottom. Scenes of the Gospel decorated the walls of the trilobate transept. Remnants of the Unbelief of St. Thomas, the Ascension, the Entry of Jesus into Jerusalem and a lone figure from the scene of the Transfiguration. Still in the crusade period the shafts of the columns were decorated with encaustic paintings from the Old and New Testaments and with Saints from the east and the west identified by texts in Greek and Latin.

Source: Holy Land of the Crusaders