By Sheila Carapico, Middle East Research and Information Project, July 14

* This memo was prepared as part of the “Ethics and Research in the Middle East†symposium

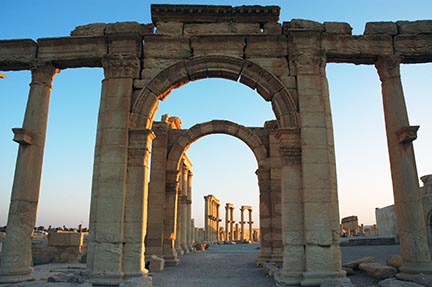

American political scientists studying the Middle East face ethical dilemmas not shared by most of our disciplinary colleagues. Sometimes – perhaps unexpectedly – our presence in countries or communities experiencing repression and/or political violence puts our local colleagues, hosts, or contacts at risk by association. The massive U.S. military footprint and widespread mistrust of U.S. policies and motives multiplies the risks to our interlocutors.

The trademark methodology of American Arabists is fieldwork, meaning, in political science, in-depth interviews, participant observation, data collection, document-gathering, opinion polling, political mapping, and recording events. As sojourners but not permanent residents, we rely heavily on the wisdom, networks, and goodwill of counterparts “on the ground,†particularly other intellectuals.

In any environment where agencies of national, neighboring, and U.S. governments are all known to be gathering intelligence, our research projects may look and sound like old-fashioned espionage. Even under the very best of circumstances (which are rather scarce) a lot of people are wary or suspicious of all Americans, including or sometimes especially Arabic speakers who ask a lot of questions and take notes. Immediate acquaintances probably grasp and trust our inquiries. Their neighbors or nearby security personnel may not. It is common knowledge that at least some spies and spooks come in academic disguise and that some U.S.-based scholars sell their expertise to the CIA or the Pentagon. Instead of treating whispered gossip as the product of mere paranoia or conspiracy theories, we need to recognize its objective and sociological underpinnings. Continue reading On The Moral Hazards of Field Research in Middle East Politics