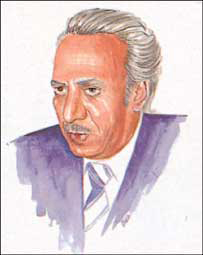

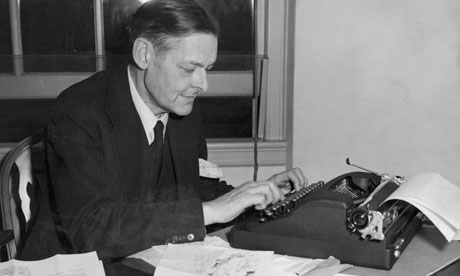

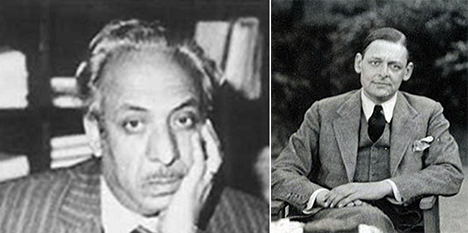

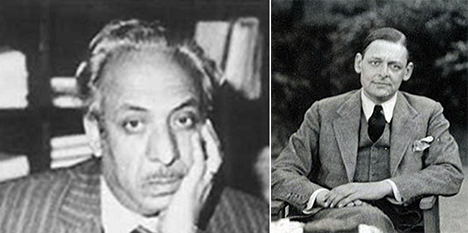

Salah Abdel-Sabour, left; T. S. Eliot, right

T. S. Eliot’s Influence Upon Salah Abdel-Sabour

By George Nicolas El-Hage, Ph.D.

The degree of influence of the Anglo-American poet, T.S. Eliot, on the Egypto-Arabic poet and dramatist, Salah Abdel-Sabour, has not yet been vastly explored. In this article, I shall not only attempt to compare the two poets in a more enlightened perspective, but I shall also probe the fundamental methodology governing a general comparative study. My approach includes the following:

1. A Valid Comparative Study and the Importance of Comparative Literature

2. Traditional Arabic Poetry

3. Why T.S. Eliot?

4. A Brief Summary of Eliot’s Background

5. A Brief Summary of Abdel Sabour’s Background

6. A Practical and Comparative Analysis of One of Sabour’s Poems

7. Abdel Sabour’s Departure from Traditional Arabic Poetry

8. A Brief Comparison between Two Plays

9. Conclusion

1. A Valid Comparative Study and the Importance of Comparative Literature

A fruitful and acceptable treatment of a subject which discusses the influence of one poet upon another must not stop at the limits of a shallow consideration of the most obvious similarities of forms, meanings, and techniques. It must go to the depths to consider the various elements that concern the sources of similarities, as well as the differences, in the light of the cultural backgrounds of the two poets. For example, a comparative study between Corneille and Racine, Wordsworth and Coleridge, and Sabour and Mahmoud Darwish would not be valid for each pair of these poets or writers belongs to the same culture and submits to the same political and social atmospheres.

Comparative Literature is neither a literary comparison nor a mere translation of a foreign literature. It is, as Jean-Marie Carre says, a study of the international and spiritual relations between men and cultures. A meaningful comparative study requires two artists belonging to remote cultures, yet dealing with the same literary genre. The comparativist, thereby, investigates the major differences existing between the environments which produced habits, customs, and verbalization of thought. Again, it appears necessary to investigate the spiritual and material factors which establish the concepts of every culture. It is also necessary to determine the degree of understanding each poet has of his own literary tradition and to ascertain the extent to which his cultural heritage pervades his poetry. The political, religious, economical, and linguistic elements are important factors to be considered. Continue reading T. S. Eliot’s Influence Upon Salah Abdel-Sabour, #1 →