By Rashid Khalidi, The Nation, March 21, 2011 and Institute for Palestine Studies, March 3, 2011

Suddenly, to be an Arab has become a good thing. People all over the Arab world feel a sense of pride in shaking off decades of cowed passivity under dictatorships that ruled with no deference to popular wishes. And it has become respectable in the West as well. Egypt is now thought of as an exciting and progressive place; its people’s expressions of solidarity are welcomed by demonstrators in Madison, Wisconsin; and its bright young activists are seen as models for a new kind of twenty-first-century mobilization. Events in the Arab world are being covered by the Western media more extensively than ever before and are being talked about positively in a fashion that is unprecedented. Before, when anything Muslim or Middle Eastern or Arab was reported on, it was almost always with a heavy negative connotation. Now, during this Arab spring, this has ceased to be the case. An area that was a byword for political stagnation is witnessing a rapid transformation that has caught the attention of the world.

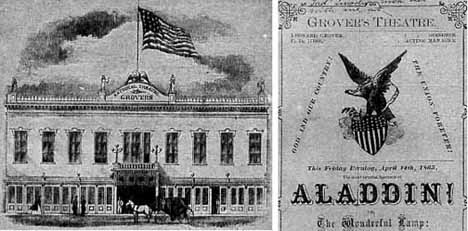

Three things should be said about this sea change in perceptions about Arabs, Muslims and Middle Easterners. The first is that it shows how superficial, and how false, were most Western media images of this region. Virtually all we heard about were the ubiquitous terrorists, the omnipresent bearded radicals and their veiled companions trying to impose Sharia and the corrupt, brutal despots who were the only option for control of such undesirables. In US government-speak, faithfully repeated by the mainstream media, most of that corruption and brutality was airbrushed out through the use of mendacious terms like “moderates†(i.e., those who do and say what we want). That locution, and the one used to denigrate the people of the region, “the Arab street,†should now be permanently retired. The second feature of this shift in perceptions is that it is very fragile. Even if all the Arab despots are overthrown, there is an enormous investment in the “us versus them†view of the region. This includes not only entire bureaucratic empires engaged in fighting the “war on terror,†not only the industries that supply this war and the battalions of contractors and consultants so generously rewarded for their services in it; it also includes a large ideological archipelago of faux expertise, with vast shoals of “terrorologists†deeply committed to propagating this caricature of the Middle East. These talking heads who pass for experts have ceaselessly affirmed that terrorists and Islamists are the only thing to look for or see. They are the ones who systematically taught Americans not to see the real Arab world: the unions, those with a commitment to the rule of law, the tech-savvy young people, the feminists, the artists and intellectuals, those with a reasonable knowledge of Western culture and values, the ordinary people who simply want decent opportunities and a voice in how they are governed. The “experts†taught us instead that this was a fanatical people, a people without dignity, a people that deserved its terrible American-supported rulers. Those with power and influence who hold these borderline-racist views are not going to change them quickly, if at all: for proof, one needs only a brief exposure to the sewer that is Fox News. Continue reading The Arab Spring →