Burton in Aden

Today is March 19. Exactly 191 years ago, at 9:30 in the evening in the British town of Torquay in Devon the future Sir Richard Francis Burton was born. Like his 2oth century acting namesake, Burton was a character for the ages. He reveled in adventure and eroticism, for which he was much reviled in public and no doubt admired in private. If any one word can be used to described the persona that Burton pursued it would be “swashbuckling” in life as in spirit. My point today is neither to praise this flamboyant quasi-Victorian Caesar nor bury him (his grave is indeed a monumental site to behold). May his dry bones rest in the kind of peace he never seems to have found in life.

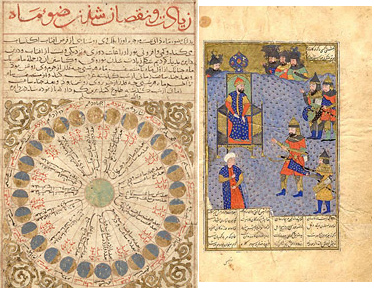

Burton’s biographers are numerous, as befits someone who is remembered as larger than life. His prolific corpus is now almost entirely online in various formats, but the place to start is burtoniana.org. There is much to question and quibble about in Burton’s exploits. Was his surreptitious entry into Mecca, disguised as a pilgrim, a travesty of Islamic values? Did his fascination with erotica in an age of gentlemananged taboos overstep ethical bounds? Was he the bad kind of “Orientalist,” a discourse cum intercourse voyeur that warrants calling him “Dirty Dick”, as Edward Said does in Orientalism (p. 190)? Was he, perhaps, a bit mad in that ubiquitous England manner?

Whatever you might think of the man, it is probably because of what you have read about him rather than what he actually wrote. Regardless of what he is saying, it must be noted that he had an extraordinary capacity for learning languages. Below is a list of the languages and dialects he is said to have mastered to some extent:

English, French, Italian, Latin, Greek, Jataki dialect (he wrote a grammar), Hindustani, Marathi, Urdu, Arabic, Persian, Pushtu, Sanskrit, Portuguese, Spanish, German, Icelandic, Swahili, Amharic, Fan, Egba, Ashanti, Hebrew, Aramaic, Many other West African & Indian dialects

I suspect he would get into Harvard, no matter what his SAT score.