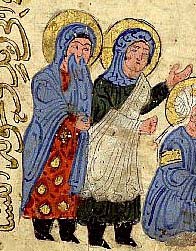

Two woman observing a conversation, Baghdad, Maqamat al-Hariri, Late Eleventh to early Twelfth Centuries, Bibliotheque Nationale, Paris. MS arabe 3929 fol 134, Maqamat 40, detail

Medieval Muslim Women’s Travel: Defying Distance and Dangerby Marina Tolmacheva, World History Connected

Women’s rights in Muslim societies became an especially sensitive subject of intercultural discussion in the twenty-first century. The recent Arab awakening has made understanding Islam, explaining Muslim sacred law to non-Muslims, and interpreting the internal dynamics of Islamic countries an increasingly urgent concern for educators. This paper focuses on historical evidence of Muslim women’s spatial mobility since the rise of Islam and until the early modern period, that is from the seventh until the sixteenth centuries. The Muslim accounts of travel and literature about travel created during this long period were written by men, mostly in Arabic. Muslim women did not leave behind records of their own travel, and it is only in the early modern period that some records were created by women, only a very few of which have been discovered. This means that we must rely on men’s accounts of women’s travel or draw on general descriptions of travel conditions that are applicable to women’s travel as well as men’s. Another limitation derives from the Islamic requirements of privacy and Muslim conventions of propriety: it was generally not considered good manners to discuss womenfolk or specific ladies, so medieval, and even early modern, Muslim books rarely describe living women unless it is to praise them. Historical chronicles may glorify queens, discuss important marriages made by princesses, or praise pious or learned Muslim women, but some travel books—for example, “The Book of Travels” (Safar-Nama) by the Persian traveler Nasir-i Khusraw (1004–1088)—do not speak of women at all. Some of the eyewitness evidence below explicitly related to women’s travel is drawn from the author who set the pattern of the travel account focused on pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn Jubayr (1145–1217) and from “The Travels” (Rihla) of by Ibn Battuta (1304–1368?), who repeatedly married and divorced during his travels and sought advantage from association with prominent women met on his journeys. No such reservation was practiced in the Christian writing tradition, so occasionally observations of Muslim women on the journey may be found in the records left by European pilgrims, merchants or captives in the Near East, especially in works published after 1500. Continue reading Medieval Muslim Women’s Travel