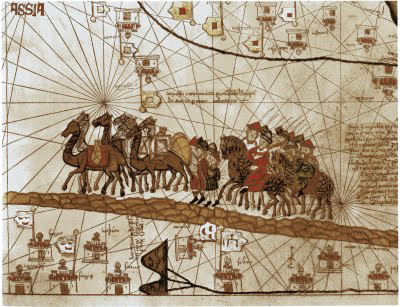

Silk Road

[One of the most widely read Holy Land travel narratives of the 14th century was attributed to a certain Sir John Mandaville. Some scholars believed it was compiled from writings of It appears to have been compiled from the writings of William of Boldensele, Oderic of Pordenone, and Vincent de Beauvais. Whoever the author, it is a fascinating read for the positive depiction of Islam. But part of the praise is to heap shame on the Christians for not keeping faith as well as these Saracens. Martin Luther used the same tactic, even accusing the Catholic Church of being worse in keeping faith than the Turks of his day. The entire book is online, but here is the part comparing Muslim and Christian devotion. For part one, click here.]

And, therefore, I shall tell you what the soldan told me upon a day in his chamber. He let void out of his chamber all manner of men, lords and others, for he would speak with me in counsel. And there he asked me how the Christian men governed them in our country. And I said him, “Right well, thanked be God!â€

And he said me, “Truly nay! For ye Christian men reck right nought, how untruly to serve God! Ye should give ensample to the lewd people for to do well, and ye give them ensample to do evil. For the commons, upon festival days, when they should go to church to serve God, then go they to taverns, and be there in gluttony all the day and all night, and eat and drink as beasts that have no reason, and wit not when they have enough. And also the Christian men enforce themselves in all manners that they may, for to fight and for to deceive that one that other. And therewithal they be so proud, that they know not how to be clothed; now long, now short, now strait, now large, now sworded, now daggered, and in all manner guises. They should be simple, meek and true, and full of alms-deeds, as Jesu was, in whom they trow; but they be all the contrary, and ever inclined to the evil, and to do evil. And they be so covetous, that, for a little silver, they sell their daughters, their sisters and their own wives to put them to lechery. And one withdraweth the wife of another, and none of them holdeth faith to another; but they defoul their law that Jesu Christ betook them to keep for their salvation. And thus, for their sins, have they lost all this land that we hold. For, for their sins, their God hath taken them into our hands, not only by strength of ourself, but for their sins. For we know well, in very sooth, that when ye serve God, God will help you; and when he is with you, no man may be against you. And that know we well by our prophecies, that Christian men shall win again this land out of our hands, when they serve God more devoutly; but as long as they be of foul and of unclean living (as they be now) we have no dread of them in no kind, for their God will not help them in no wise.†Continue reading Travels of Sir John Mandaville, 2 →