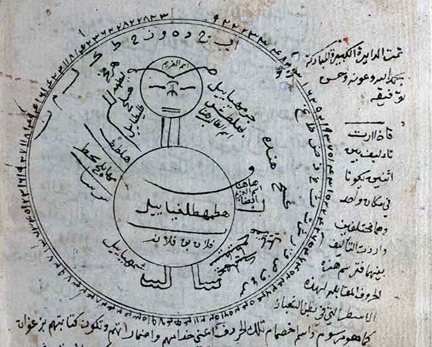

Unnamed tulip from the Turkish ‘The Book of Tulips’, ca. 1725

Webshaykh’s Note: With winter snow buffeting Europe and the Middle East, what better time to think about tulips, an Ottoman treasure that took Europe by storm almost half a millennium ago. There is an excellent book on The Tulip by Anna Pavord (Great Britain: Bloomsbury, 1999), but one of my favorite articles is one that Jon Mandaville wrote for ARAMCO World over three decades ago. The full article is available online, but I provide the first part below.]

Turbans and Tulips

Written by Jon Mandaville. ARAMCO World Magazine, May/June, 1977

Tulips come from Holland. Right? Wrong! Or at least, they haven’t always. Tulips come from Turkey, the only country in the world to call one of its major eras of national history—the years 1700 to 1730—the “Tulip Period.” And how that era got its name . . . thereby hangs a tale.

Tulips, even in the early 18th century, were nothing new to Turkey. Along with other bulbous plants such as the narcissus, the hyacinth and the daffodil, tulips had grown there for centuries, both wild and domesticated for house and garden. The Tulip Period took its name from an established hobby, which started as court fashion, grew into a generalized fad and fancy, and finally became an explosion of unrestrained international speculation in bulbs which buyers never even saw.

It all began when tulips first went to Europe. In 1550, no one in Holland had heard of tulips. Different varieties do grow wild in North Africa and from Greece and Turkey all the way to Afghanistan and Kashmir. Very occasionally they are even found in southern France and Italy, usually in vineyards or on cultivated land, which has led some botanists to speculate that they may have been brought back by the Crusaders.

The Persians were familiar with tulips, but they didn’t domesticate them as thoroughly as the Turks. For centuries they admired the flowers wild. Even as decorative motifs in Persia, they were never as popular as the narcissus, iris or rose.

In Turkey it was different. Continue reading Tulip mania →