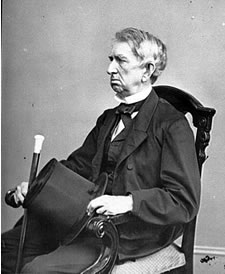

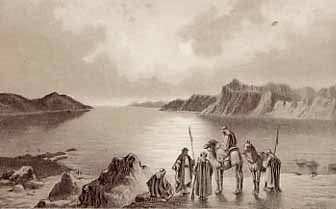

As a child I spent many inquisitive hours leafing through the books in my grandmother’s parlor bookcase. One that especially attracted my attention was John Kitto’s An Illustrated History of the Holy Bible (Social Circle, Georgia: E. Nebhut, 1871). Rev. John Kitto, recognized on the title page as author of the London Pictorial Bible, the Cyclopedia of Biblical Literature, ETC, ETC, retells the entire history of the Old and New Testament, from creation to the destruction of Jerusalem. Kitto was born into poverty in 1804 in Plymouth, England and due to an unfortunate accident ate age thirteen became entirely deaf and was forced into the poor house at the age of fifteen. This is quite an inauspicious beginning for a waif who went on to be a respected theological scholar. Through the local humanitarian efforts of several men in Plymouth, Kitto became a lay missionary to Malta and then for three and a half years in Baghdad. “While residing in that city,†writes Alvan Bond in the preface to Kitto’s book, Cairo “was visited by the plague, the terrific ravages of which swept off more than one-half the inhabitants in two months. Amidst this fearful desolation he remained calm and active at his post.†Once back in England he married and produced a travel account and several pictorial histories of the Holy Land. In 1844 the University of Giessen conferred upon him the degree of D.D. His ill health forced him to seek help in the spas of Germany, where he died after a mere half century in 1854. Continue reading With Kitto Illustrating Bible History