The Nobel Peace Prize for 2011 has just been released with three recipients: Ellen Johnson Sirleaf, Lehmah Gbowee and Tawwakul Karman. All three were chosen “for their non-violent struggle for the safety of women and for women’s rights to full participation in peace-building work.” Karman is Yemeni; but beyond this she is the first Arab woman to win a Nobel prize, a point proudly noted on the Yemeni media site Yemen Press. It will be interesting to watch the reaction to the choice. Here is an activist who took to the streets to promote a peaceful transition from the corrupt secular dynasty of Ali Abdullah Salih. She is one of many Yemenis sharing the same goal and not a principle organizer, although her superb English skills attracted attention in the foreign media. She is also actively involved in the powerful Islamic party of Islah.

As always there will be much second guessing as to why these particular individuals were chosen. I suspect that Karman was not near the top of any speculation list. The Nobel Peace Prize, however, is the most symbolic of these “dynamic” Swedish awards, with the aim of promoting an idea more than finding the “best qualified” candidate. The stated aim this year, however, was a focus on the role of women as peacemakers. Fortunately there are many women activists peacefully advocating against corrupt politics and prejudicial practices. The choice this year appears to be a consciously rounded decision, also including the Liberian president Ellen Sirleaf and Lehmah Gbowee, a social worker also involved in the peace movement in Liberia. If it had just been Sirleaf, one might have dismissed the choice as yet another politician, no matter how worthy, but including Gbowee and Karman may have more to do with inspiring more women to participate at the local level than their actual accomplishments or impact.

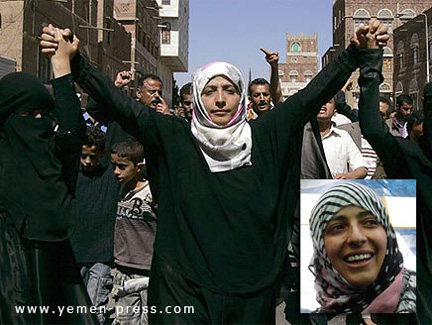

As a senior member of the prominent Yemeni Islamic party Islah, Karman does not fit the mold most Westerners hold of Muslim women. She covers her hair with a scarf, but without the extreme niqab or even the more ubiquitous Yemeni sharshaf ( a full-length black outer veil introduced to Yemen by the Ottoman Turks). While the media is for the most part fixated on the masculine culture of Al Qaida, the role of women in Yemen is either ignored or stereotyped. So this choice will draw attention to the fact that there are women who are proud to be Muslim and do not view themselves as servile slaves. But it will also, I suspect, result in detractors within Yemen who will be jealous of the attention she is receiving and perhaps even dismiss it as yet another “Western†intrusion. Will the leaders of Islah promote this honor to one of their members? Will rival Islamic groups use her as a wedge issue?

Whatever the fallout is from choosing a Yemeni woman for this honor, at least there is finally an alternative image to the sad metaphor of the Muslim woman as mother of a martyr. Yes, there are mothers who rightfully grieve for the deaths of their sons and husbands. But this is a tragedy that too often leaves no room for other ways in which Muslim women participate in the political process. Yes, there are pathetic Muslim men who think bundling their wives and daughters away in seclusion is a spiritual rather than a cultural act (which is hardly unique to Muslim culture). Just as the world has rid itself of the scourge of human slavery, the handwriting is on the twitter with younger generations everywhere who see misogyny as a travesty and shame. Yes, Muslim women do have voices and many share with women all over the world and across faiths a desire for peace and the safety of their loved ones.

But will this media attention on the Yemen protests have any impact on the eventual departure of Salih? Ironically, Salih has over the years accepted the role of women in the Yemeni government. He is hardly a feminist, and he has been too quick to give in to extreme demands, but at least he has not touted a cleric’s mentality. Yemeni society in the north has seen the economic role of women in agriculture diminished, their freedom of movement curtailed and outside pressure from Salafi groups to erode women’s rights. The more open society with acceptance of women in many government positions during the form socialist regime in the south has collapsed with foreign money and thinking instituting a misogyny that neither Yemen held in the past. Salih will eventually leave power and his legacy will not be one to be proud of. The Nobel Peace Prize choice will not push him out, but perhaps the pride that Yemenis can share in having the first Arab Muslim woman for such an honor will keep the peace process moving in the right direction. Stay tuned and give peace a chance.

Daniel Martin Varisco