Long before Abraham/Ibrahim left Ur of the Chaldees for the promised land and became the ancestral icon of Judaism, Christianity and Islam, there was that architectural wonder called the Tower of Babel. As noted in the eloquent phrasing of the King James Version of Genesis 11:4: “And they said, Go to, let us build us a city and a tower, whose top may reach unto heaven; and let us make us a name, lest we be scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth.” Readers of the text know what happened with that bravado venture. As a refresher, here is how the artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder imagined that ziggurat tower in 1563.

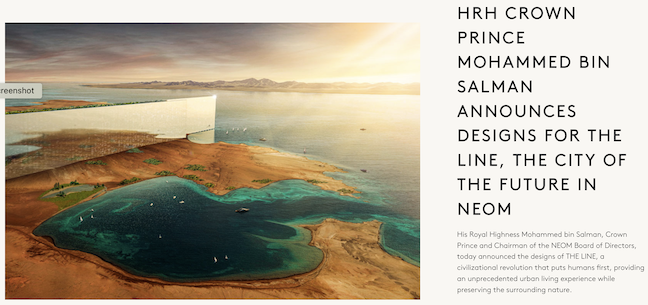

Now what if instead of a massive tower, such an old-fashioned idea, a new world wonder was created with the narrow ribbon of an artificial skyscraper city some 75 miles long, and some 656 feet wide? One set of plans would make this the most eco-friendly living space ever conceived:

THE LINE will eventually accommodate 9 million people and will be built on a footprint of just 34 square kilometers. This will mean a reduced infrastructure footprint, creating never-before-seen efficiencies in city functions. The ideal climate all-year-round will ensure that residents can enjoy the surrounding nature. Residents will also have access to all facilities within a five-minute walk, in addition to high-speed rail – with an end-to-end transit of 20 minutes.

This rival to The Pyramids would reach 1600 feet into the sky, thus becoming taller than the World Trade Center that several Saudi citizens destroyed in 2001 by crashing an airplane into the building. Of course such a major building enterprise would cost a lot of money, like a trillion dollars. I wonder what country would have that kind of funding available and what kind of resurrected Nimrod would think of such an idea?

Guess what? The plans are now on the board with the NEOM project known as “The Line”. You can read all about it on all kinds of websites, like NPR, The Independant, The Guardian, Time Out, and many other sources by typing “NEOM The Line” into Google. The patron of this marvel is His Royal Highness (I guess the Highness in his title inspired the idea to have the highest city in the world) MBS of the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. It would have been nice to read a review of this fiasco by the Saudi journalist Jamal Kashoggi, but he is no longer around.

Of all the places on earth, where would be the best location for this ethereal construction project? Why not at the crossroads of the planet? Now that all roads no longer lead to Rome, I guess that would be the Arabian desert in Saudi Arabia. After all who would not want to live in a natural setting with miles and miles of sand and rocks and hardly any sign of wildlife? Unfortunately there are only a few camels left in the Saudi desert, since most are now getting ready for beauty pageants. But at least there will not be the nuisance of fast-driving joy-riding by Saudi youth through the streets, since there will not be any streets. Instead, I suspect that people will get around by doing what they did on the TV show The Jetsons. Of course, Saudi lifestyles will still be enforced, so women will need a male escort and be veiled before taking that five-minute walk to anything they desire.

World reaction to this marvel of marvels is just beginning. Carlos Felipe Pardo informed NPR that “This solution is a little bit like wanting to live on Mars because things on Earth are very messy.” The choice of Mars is proper, since Venus would not be a good metaphor for Saudi censors due to all the naked images of the goddess Venus that are available on the web. I think there would be a positive response from endangered dictators like Vladimir Putin, since the Saudi government has given sanctuary to all kinds of nasty rulers in exile in the past, most recently Ben Ali of Tunisia. Idi Amin, the brutal ruler of Uganda, but clearly thought to still be a good Muslim in the Saudi style, spent his latter years in luxury as a guest of the Saudis.

The Tower of Babel was doomed from the start, but then Nimrod and his like did not realize the vast oil and gas wealth underneath their feet in the Middle East. If they had, we would all be speaking the same language that Adam and Noah spoke. Even Star Trek never imagined that.