“After a short naval bombardment, Tripoli fell to 1500 Italian sailors on October 3, 1911”

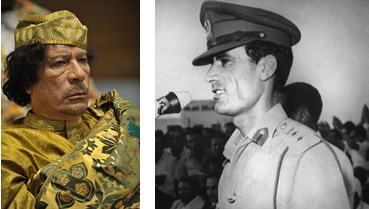

Watching the media coverage of the “rebel” pick-up entry into the outskirts of Tripoli is a chilling reminder that we continue to be a culture of spectator pornography. I can imagine my ancient Roman ancestors quaffing goblets of wine as they reveled in the blood flowing from indentured swordsmen and Christian martyrs fed to the lions. How little is changed when fans break out in fights at a pre-season American football game and soccer hooliganism remains a curse on civility in Britain. On our screens we see the sanitized version of war, of course, not the sun-scorched corpses, the unrecognizable twisted body parts, the agony at the receiving end of grenade blast. The number of casualties, invariably inflated by some and deflated by others, is duly noted as though it could be the up and down daily tick of the stock market. Ah yes, the “mad dog” of Libya, ruthless dictator as he clearly has been, is about to disappear from the scene. Hooray for the good guys…

One can celebrate the overturn of a dictatorial regime, but is it ever worth celebrating individual deaths? Martyrs are always those who die on your own side; the other bodies might as well be animal dung. This was the fate of Mussolini at the end of World War II. History will be rewritten by those who assume power, but the memories of widespread destruction will continue to haunt a generation or two or three or more. The pain continues because old wounds are continually reopened and the scars never really go away. If you live through a war, that war will not die with you as an individual; often, not even with a generation.

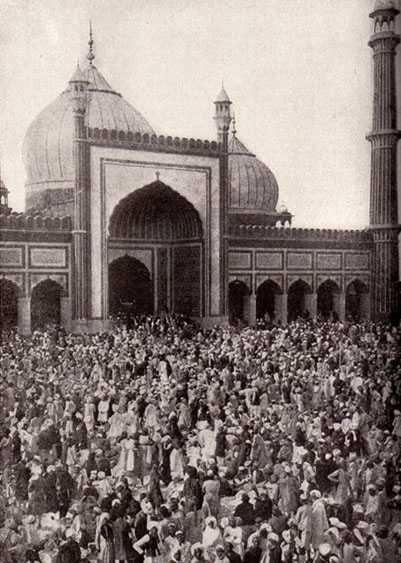

There is nothing new going on in Libya; it is the age-old toppling of one regime and ascendancy of another. The Phoenicians had their turn; then the Romans; then the barbarians that swept through Rome, the Ottomans and then again the Italians in 1911. There is always this sense that this time around it may be permanent, a road to future progress. Clearly, almost any kind of regime in Libya after Qaddafi will be better for most people, but in the broad historical perspective it may only be one pendulum swing in the sad history of humanity’s intolerance. No, the problem is not Islam, not the West, not the monetary policies of the World Bank, not even fascism, communism or any specific ideology. We have evolved as a species dependent on cooperation because we also have the propensity of a will to power over others. Those who fight for peace, often by refusing to fight in the mode of a Gandhi, only highlight the fact that peace is not the normal state of affairs for our species over the long haul. The hope that one day a Messiah, a Jesus, or any dreamed up deliverer, will come and set things straight is as old as the need for such a hope.

There is an old Arabic proverb, ba’d kharab Basra (after the destruction of Basra), one that gained new resonance during the regime of Saddam Hussein in his disastrous war with Iran and then the two Gulf Wars that eventually brought about his end. So now is it to be ba’d kharab Tripoli? Continue reading Ba’d kharab Tripoli