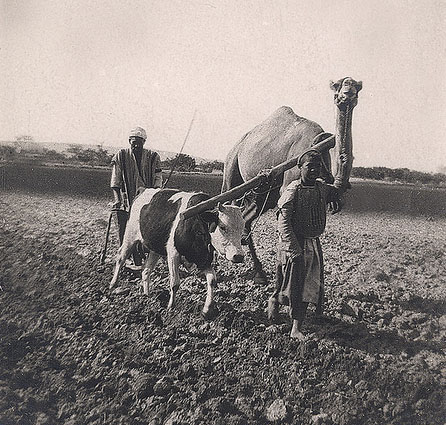

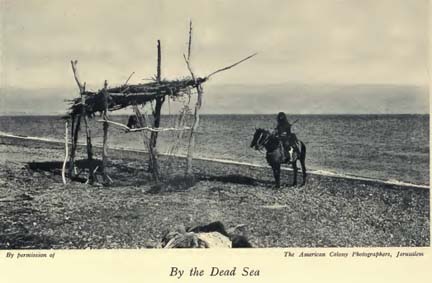

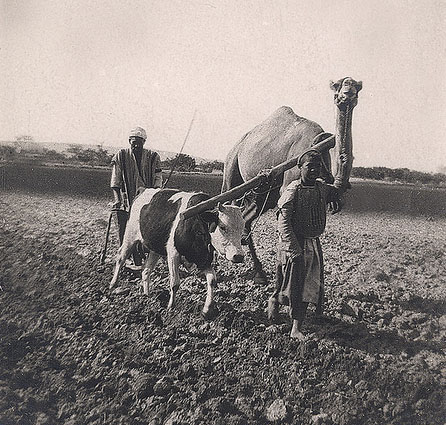

Gelatine silver print (probably made in the mid-1920s) of an American Colony photograph taken in southern Palestine between 1898 and 1911; from the John Garstang collection

“Be ye not unequally yoked together with unbelievers; for what fellowship hath righteousness with unrighteousness? And what communion hath light with darkness?” 2 Corinthians 6:14, KJV

The admonition of the Apostle Paul in his second letter to Corinth is the ultimate justification for separatism. Orthodox Jews, Fundamentalist born-again Christians and ultra-conservative Muslims all have taken to heart the sentiment of this advice, often making it into an outright ban. The latest news sensation is about a Muslim “catacomb sect” in Russia’s Tatarstan region:

Four members of a breakaway Muslim sect in Russia’s Tatarstan region have been charged with cruelty against children for allegedly keeping them underground.

Police discovered 27 children and 38 adults living in catacomb-like cells in an eight-level underground bunker.

The sect’s elderly leader, Faizrakhman Sattarov, had reportedly wanted to build his own Islamic caliphate beneath the ground…

Officials said the children, aged between one and 17 years, had never left the compound, gone to school or been treated by a doctor, and had rarely seen the light of day.

According to the Russian website Islam News, Mr Sattarov, 83, declared himself an Islamic prophet in the mid-1960s after interpreting sparks from a trolleybus cable as a divine light from God.

He and his followers began to shun the outside world in the early part of this century.

One is not sure to laugh or cry at a prophet who gets his revelation from the sparks of a trolleybus cable, but in the end a vision is a vision no matter what the alleged divine source. All three major religions have had their break-away, nothing-to-do-with-this-life prophets and the few sheep that inevitably follow them over the cliff of rationality. The problem here is what may be labeled a dogmatic emphasis on the “unsocial contract.” In other words, this is a kind of cultural suicide, hardly the umma envisioned by the Prophet Muhammad.

The metaphor in the old photograph above is what intrigues me. The supposed rationale is that a team of domestic animals should be the same, generally two oxen. That is all well and good if you actually have two of these rather expensive beasts, but what if you don’t? In many cases farmers in the region had to make due with either a donkey or a camel, but hitching two different animals may not have been as rare as assumed, nor as problematic. Notice in this image that a little boy leads the camel, allowing it to keep the pace of the ox while the ploughman bears down on the blade. Rather than focus on there being two separate animals, think about the social cooperation of boy, man, ox and camel as a unit.

When the emphasis is on what makes the animals different either from each other or from humans, the broader point of cooperation is easily lost. The same is true in religion. Separatists are doomed to failure by their very nature, except as oases sustained within a wider pluralistic context. Those sects which survive learn to adapt to competing views and accept change, no matter what level of reticence. Consider the early Mormons, who were so far out of the mainstream that they were persecuted everywhere they went. No matter the doctrines still enshrined on the main webpage of the Church of Latter Day Saints, the church has embraced the very kind of patriotism that once forced them to the arid wilderness of Utah. This is the only way they could have survived.

I am certainly no prophet, even though I have seen trolleycar sparks in my youth, but I suspect that the future of Islam will see increasing rather than decreasing pluralism. As a religion which has spread well outside its Arabian geographic origin, the ways of being Muslim are far too many to ever be bottled into one halal variety. Even in the heyday of Islamic power there was never a unanimity of belief. Like Judaism and Christianity there will continue to be those who insist they represent the “true” faith, but no religion can resist the perpetual cultural change that envelops the entire globe. Think of that Palestinian fellah in the 1920s photograph above. He could never have imagined the technological and social change in his own backyard today. Today we think we can imagine, but the future is probably not best revealed by looking at a trolleycar, sparks or not.